Resources

In Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, James W. Loewen finds several problems with how slavery is taught in high schools across the United States. Loewen observes that white Americans remain perpetually startled at slavery. Even many years after high school, white adults are aghast when confronted with the horror and pervasiveness of slavery in the American past. It seems they did not learn, or have quickly forgotten, that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were among the multitudes of white Americans who owned enslaved Black Americans as their human property. Loewen surmises the ignorance of white Americans on slavery can be traced back to high school classrooms. History textbooks incorrectly present slavery as an uncaused tragedy and minimize white complicity in the enslavement of Black Americans. Students are meant to feel sadness for the plight of four million enslaved Black persons in 1860, but not anger toward the approximately 390,000 white slaveowners because these slaveowners, and their unjust actions, do not appear in the pages of the textbooks. Since Loewen published his book in 1995, there have been strides to improve the teaching and learning on slavery. One notable example is the introduction of lesson plans based on the 1619 Project from the New York Times in middle and high school classrooms in Baltimore, Buffalo, Chicago, Newark, Washington, D.C., and other cities. Yet, the backlash against a more comprehensive curriculum on slavery, which is most visible in President Trump’s recent call for a “1776 Commission” to directly challenge the pedagogy of the 1619 Project, reveals the need for an assessment of how theological schools are engaging these educational debates around slavery. As I reflect on my experiences as a theological student and educator, I am concerned seminary classrooms are also failing to provide instruction that properly captures the totality of white Christian involvement in slavery and anti-Black racism. The perpetual shock in some white congregations over some basic historical facts about slavery is alarming. One pernicious myth I encounter is the notion that most white Christians in the antebellum period were abolitionists pushing for the immediate emancipation of enslaved Black persons. This is simply not true. Very few white Christians held this position and there was little support for immediate emancipation in the Baptist, Episcopalian, Methodist, and Presbyterian denominations. Many white Christians in the southern states defended slavery so vigorously that some Black and white abolitionists identified white churches as the most impenetrable strongholds against their cause. Benjamin Morgan Palmer, a white Presbyterian pastor in New Orleans who previously taught at Columbia Theological Seminary, preached in 1860 that slavery was a providential trust that whites must preserve and perpetuate because the natural condition of Black Americans was servitude. Palmer mocked northern abolitionists for thinking that Black Americans could survive alongside whites as equals. Palmer was neither reviled nor rebuked for his white supremacist views. Rather, he was widely celebrated and elected to serve as the first moderator of the newly formed Presbyterian Church of the Confederate States of America in 1861. Black Christians like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth emphasized the eradication of anti-Black racism as an essential component in their abolitionism. But even white Christian abolitionists in the northern states fell woefully short in their advocacy against anti-Black racism. Archibald Alexander, a white theologian and professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, endorsed the colonization movement to send free Black Americans to Liberia, because he felt the discriminatory contempt white Christians held against Black Americans was too insurmountable to overcome. In 1846, Alexander wrote that anti-Black racism was wrong and unreasonable, but he did not commit to working toward racial equality. Instead of teaching white Christians to repent of their racism and white supremacy, Alexander preferred Black Americans, once emancipated, leave the country and find another home where their skin color would not be despised. Seminary classrooms may not treat slavery as an uncaused tragedy, but I believe some of our teaching and learning in theological education also minimizes white Christian complicity and misdirects the anger students should feel about slavery. Rather than fully grappling with the histories and legacies of economic exploitation, sexual violence, and virulent anti-Black racism perpetrated by white American Christians, students are left with a neatly packaged lesson on slavery centered on the dangers of deficient biblical interpretation and proof-texting the Scriptures. Such instruction misses a crucial point the abolitionists themselves made, which was to identify and confront the anti-Black racism of white Christians. In 1845, Frederick Douglass differentiated between genuine Christianity and the “corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land” in his autobiographical narrative. In the ongoing pursuit of racial justice today, our seminary classrooms must also engage in teaching a more complete history of slavery and white American Christianity.

2020 Teaching Workshop for FTE Doctoral Fellows September 24-26 (Online) Co-sponsored with the Forum for Theological Exploration Eligibility is by invitation from FTE. Leadership Team: Brian Bantum,Seattle Pacific Seminary Monica Coleman,University of Delaware Mary Stimming,Wabash Center Top Row: Christopher Hunt (Colorado College), Mary Stimming* (Wabash Center), Eliezer Rolón Jeong (Claremont School of Theology), Elyse Ambrose (Drew University) Second Row: Brian Bantum* (Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary), Joel Kemp (Candler School of Theology-Emory University), Leonard Curry (Berea College), Monica Coleman* (University of Delaware) Third Row: Renee Monkman (Wycliffe College), Timothy Rainey (Emory University), Junehee Yoon (Drew Theological School), Yuki Schwartz (Justice Leadership Program) Fourth Row: Lisa Dellinger (Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary), Marvin Wickware (Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago), Itohan Idumwonyi (Gonzaga University), Kyle Brooks (Methodist Theological School in Ohio) Fifth Row: Amaryah Armstrong (Virginia Tech State University) * leadership/staff position

On Wednesday, October 7, 2020 we had our first gathering with Victor Wooten and the fifteen scholars who are privileged to be a part of this cohort. Victor asked us, “Why are you here?” Many answered while I listened. I didn’t speak during the formal two hour period, I listened. I hadn’t intended not to speak. Prior to the gathering formally beginning I was my normal raucous self but when Dr. Lynne Westfield called us to order my posture changed. If would’ve answered the question Victor posed I would’ve said: “I am here because I love music. I am here because I use music in all of my classes. I am here because I thank improvisation is the key to living full and adventurous life. I love the guitar. I love the bass. I am grew up listening to Larry Graham, Bootsy Collins, James Jamerson, Jaco Pastorious and so many more. I am a true fan of Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miler, Chritian McBride and Victor Wooten. Victor Wooten is not simply a musician but to me he is a mystic, a teacher, a scholar and brilliant. Whenever Victor Wooten is in town I am there to be a part of the experience.” Everytime Victor comes to Atlanta I am there (the links below are to photo galleries of two of my recent experiences at a Victor Wooten concert). Victor Wooten at the Variety Playhouse in Atlanta, GA https://flic.kr/s/aHskZV22bG https://flic.kr/s/aHskzJKr6A I was in this cohort for the experience. I wanted to experience what it meant to be with Victor and my colleagues to do this work together, to grow together and reimagine what teaching could be for us in the present age. [embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GONEnFyj73w[/embedyt]

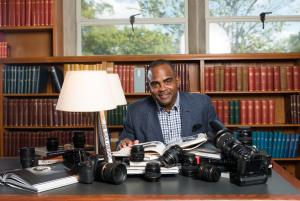

Even for the seasoned scholar, understanding the digital mindset as well as navigating educational platforms is a necessity for effective teaching. Incorporating new collaborations and resources is a key to effective classroom experiences and learner success. Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield hosts Dr. Gay L. Byron (Howard University School of Divinity).

The courses and conversations needed to teach away from white supremacy and toward equity, freedom and humility require new conversation partners, creating new kinds of courses, and bravery. Such a conversation emerged when Dr. Smith (Columbia Theological Seminary) welcomed Dr. Ulrich (Bethany Theological Seminary & Earlham School of Religion) and students from their respective schools into a new course that she developed and taught on African American and Womanist hermeneutics and the Gospel of Luke. Smith and Ulrich will reflect on what they have learned through that experience, which has included consultations and writing supported by the Wabash Center. Learning in consultation throughout the project took imagination, patience, and vulnerability.

Nurturing sensibilities and sensitivities for the pluralism of identities is a challenge to teaching and learning, alike. Teaching what you know is only the starting point.