Resources

Interdisciplinarity—or the interrelationships among distinct fields, disciplines, or branches of knowledge in pursuit of new answers to pressing problems—is one of the most contested topics in higher education today. Some see it as a way to break down the silos of academic departments and foster creative interchange, while others view it as a destructive force that will diminish academic quality and destroy the university as we know it. In Undisciplining Knowledge, acclaimed scholar Harvey J. Graff presents readers with the first comparative and critical history of interdisciplinary initiatives in the modern university. Arranged chronologically, the book tells the engaging story of how various academic fields both embraced and fought off efforts to share knowledge with other scholars. It is a story of myths, exaggerations, and misunderstandings, on all sides. Touching on a wide variety of disciplines—including genetic biology, sociology, the humanities, communications, social relations, operations research, cognitive science, materials science, nanotechnology, cultural studies, literary studies, and biosciences—the book examines the ideals, theories, and practices of interdisciplinarity through comparative case studies. Graff interweaves this narrative with a social, institutional, and intellectual history of interdisciplinary efforts over the 140 years of the modern university, focusing on both its implementation and evolution while exploring substantial differences in definitions, goals, institutional locations, and modes of organization across different areas of focus. Scholars across the disciplines, specialists in higher education, administrators, and interested readers will find the book’s multiple perspectives and practical advice on building and operating—and avoiding fallacies and errors—in interdisciplinary research and education invaluable. (From the Publisher)

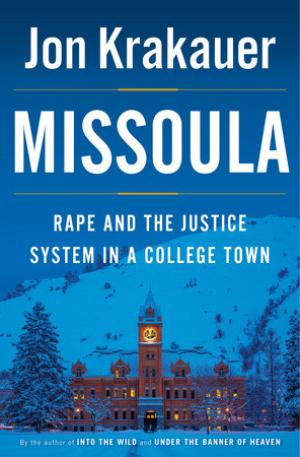

Click Here for Book Review Abstract: Missoula, Montana, is a typical college town, with a highly regarded state university, bucolic surroundings, a lively social scene, and an excellent football team - the Grizzlies - with a rabid fan base.   The Department of Justice investigated 350 sexual assaults reported to the Missoula police between January 2008 and May 2012. Few of these assaults were properly handled by either the university or local authorities. In this, Missoula is also typical.   A DOJ report released in December of 2014 estimates 110,000 women between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four are raped each year. Krakauer’s devastating narrative of what happened in Missoula makes clear why rape is so prevalent on American campuses, and why rape victims are so reluctant to report assault.   Acquaintance rape is a crime like no other. Unlike burglary or embezzlement or any other felony, the victim often comes under more suspicion than the alleged perpetrator. This is especially true if the victim is sexually active; if she had been drinking prior to the assault — and if the man she accuses plays on a popular sports team. The vanishingly small but highly publicized incidents of false accusations are often used to dismiss her claims in the press. If the case goes to trial, the woman’s entire personal life becomes fair game for defense attorneys.   This brutal reality goes a long way towards explaining why acquaintance rape is the most underreported crime in America. In addition to physical trauma, its victims often suffer devastating psychological damage that leads to feelings of shame, emotional paralysis and stigmatization. PTSD rates for rape victims are estimated to be 50%, higher than soldiers returning from war.   In Missoula, Krakauer chronicles the searing experiences of several women in Missoula — the nights when they were raped; their fear and self-doubt in the aftermath; the way they were treated by the police, prosecutors, defense attorneys; the public vilification and private anguish; their bravery in pushing forward and what it cost them.   Some of them went to the police. Some declined to go to the police, or to press charges, but sought redress from the university, which has its own, non-criminal judicial process when a student is accused of rape. In two cases the police agreed to press charges and the district attorney agreed to prosecute. One case led to a conviction; one to an acquittal. Those women courageous enough to press charges or to speak publicly about their experiences were attacked in the media, on Grizzly football fan sites, and/or to their faces. The university expelled three of the accused rapists, but one was reinstated by state officials in a secret proceeding. One district attorney testified for an alleged rapist at his university hearing. She later left the prosecutor’s office and successfully defended the Grizzlies’ star quarterback in his rape trial. The horror of being raped, in each woman’s case, was magnified by the mechanics of the justice system and the reaction of the community.   Krakauer’s dispassionate, carefully documented account of what these women endured cuts through the abstract ideological debate about campus rape. College-age women are not raped because they are promiscuous, or drunk, or send mixed signals, or feel guilty about casual sex, or seek attention. They are the victims of a terrible crime and deserving of compassion from society and fairness from a justice system that is clearly broken. (From the Publisher)

A spreadsheet Google Doc comparing a range of e-tools that support differentiation of instruction to support learner needs, created and maintained by education consultant John McCarthy.

Click Here for Book Review Abstract: Best Practices for Flipping the College Classroom provides a comprehensive overview and systematic assessment of the flipped classroom methodology in higher education. The book: • Reviews various pedagogical theories that inform flipped classroom practice and provides a brief history from its inception in K–12 to its implementation in higher education. • Offers well-developed and instructive case studies chronicling the implementation of flipped strategies across a broad spectrum of academic disciplines, physical environments, and student populations. • Provides insights and suggestions to instructors in higher education for the implementation of flipped strategies in their own courses by offering reflections on learning outcomes and student success in flipped classrooms compared with those employing more traditional models and by describing relevant technologies. • Discusses observations and analyses of student perceptions of flipping the classroom as well as student practices and behaviors particular to flipped classroom models. • Illuminates several research models and approaches for use and modification by teacher-scholars interested in building on this research on their own campuses. The evidence presented on the flipped classroom methodology by its supporters and detractors at all levels has thus far been almost entirely anecdotal or otherwise unreliable. Best Practices for Flipping the College Classroomis the first book to provide faculty members nuanced qualitative and quantitative evidence that both supports and challenges the value of flipping the college classroom. (From the Publisher)

Click Here for Book Review

Journal Issue. Full text is available online.

Journal Issue. Full text is available online.

Journal Issue. Full text is available online.

Journal Issue. Full text is available online.

Journal Issue. Full text is available online.