Book Reviews

In Academic Freedom at American Universities,Philip Lee presents a convincing case for transforming higher education with respect to protecting and encouraging true academic freedom of professors – in both public and private university settings. In six chapters, Lee discusses: the crisis of academic freedom in modern universities and the American Association of Universities Professors (chapter 1), the AAUP’s first policy declaration in 1915 and its struggle to defend academic freedom (chapter 2), the AAUP’s seminal 1940 statement and judicially defined academic freedom during the McCarthy era (chapter 3), modern constitutional conceptions of academic freedom (chapter 4), the limitations of constitutionally-based professorial freedom (chapter 5), and contract law as an alternative and better professorial academic freedom (chapter 6), an expounding of the author’s central proposal. Lee chronicles the shortcomings of constitutionally-based academic freedom and appealing to the First Amendment alone, which he seeks to demonstrate has failed to sufficiently protect public institution professors, while not even applying to private university faculty. Thus, Lee proposes an alternative remedy: “developing a body of contractually based academic freedom case law,” which will “greatly expand the ways that courts protect aggrieved professors when their interests diverge with their employers’” while also allowing for “the proper consideration of the custom and usage of the academic community as either expressed or implied contract terms in resolving disputes between universities and professors” (145-46). The author adds that this contract law approach would also entail the courts giving greater attention to specific campus contexts rather than seeking to create universal remedies that inevitably fall short of fitting certain campus settings. Professor Lee’s research demonstrates substantial mastery of the subject matter and relevant materials – no less for matters dating from the pre-AAUP period through its founding and early years of development to its expanding influence and most recent iterations. Lee’s work evidences careful scholarship that includes extensive collecting, scrutinizing, and evaluating of various crucial events, court cases and findings, written opinions, and other relevant materials spanning the AAUP’s organizational history. Particularly insightful is the author’s discussion of the 1918 report on academic freedom in wartime and the report’s multiple contradictions to the 1915 declaration’s principles, culminating in actual “retreat from professional self-identification in deference to the government’s claimed needs during wartime” (33). Also instructive is Lee’s examination of the shift in focus and language between the 1925 and 1940 Conference Statements – mainly from a prescriptive list of university “don’ts” to descriptive university teachers’ rights with the latter’s garnering of widespread acceptance (47) and approval within the bounds of most religious schools as well (64). The author’s writing style is consistently clear and engaging – no mean feat considering the rather technical and procedural materials encompassing much of this book. Philip Lee’s Academic Freedom at American Universities presents an important argument for an alternative – contract law – foundation for professorial freedom in the academy. I recommend the book as a valuable resource for all public and private higher education institutions, particularly their faculty and executive administration.

This book is meant to be put into someone’s hands in the months before they begin college, but it also serves as a useful tool for anyone contemplating returning to school after time away – adults getting ready to begin seminary, for example, after years in first or second careers – or for anyone wishing to become a “life-long learner,” whether in formal academic circles or in private life. Written in accessible language and peppered with illustrative examples, this slim volume blends common sense – such as eat a healthy, balanced diet, make time for regular exercise, get enough sleep, don’t cram – with a wide array of insights from neuroscience research and learning theory of the last fifteen years. Both authors have extensive experience and publications focused on the integration of cognitive research, biology, and learner-centered teaching: Doyle at Ferris State University and Zakrajsek in the Department of Family Medicine at UNC-Chapel Hill. The topics covered in the eight main chapters focus on learning and: sleep, exercise, the use of multiple senses, discovering and utilizing patterns, memory, “fixed” versus “growth” mindsets, and paying attention. Each chapter quickly sets forth recent pertinent research, then concludes with five to ten summary points. Much of the material in the early chapters confirms common sense: getting enough sleep and exercising regularly are necessary for both learning and memory. The brain needs “down” time to process new information. Because sleep and exercise are so foundational for learning, these topics pop up repeatedly in subsequent chapters, especially in the discussions of memory and paying attention. The discussions in chapters 4 through 8 take up facets of cognitive and learning research that move beyond common sense. Where two or more senses are put to use both learning and memory increase: for example, listening and reading, or reading aloud, or sight and touch. Even studying near the scent of roses has a positive impact. Elaboration is another key: the more routes one takes to the goal – such as via concept maps or annotating the pages of books – the stronger the learning. One chapter describes many ways of discerning patterns and “chunking” blocks of information to help make learning easier and faster. The chapter on memory reminds us that cramming is not nearly as effective as “distributed practice,” processing material in smaller bites over a longer period of time, which gives the brain time – it needs at least an hour – to do its work. This means that taking classes back-to-back, with little or no break in between, is nearly always a bad idea, especially in regard to the material in the first class. Resting between classes or learning activities, as well as taking short naps and breaks, daydreaming, or going for a walk or run, turn out to be essential for effective learning. Many students are told in elementary school how smart they are, as if learning is a fixed attribute, rather than being praised for the hard work they are doing, which affirms their learning as a process of steady “growth.” As a result, they often have difficult transitions in middle school and beyond, where the material demands more and more effort. Long-term success is a result of steady work and effective learning strategies, not intelligence. The New Science of Learning’s extensive use of citations provides lots of trails to follow if the reader is inclined to go deeper, but also makes the book choppier and less engaging than if the authors had rephrased the information in their own words. But this is a minor quibble. I plan to give a copy of this book to my son, who will start college next year, as well as my daughter, a high school sophomore, mostly because I learned so much about how to learn that I wish I had known long ago.

How might arts-based teaching, learning, and research transform education? This question is explored by demonstrating that arts-based methods and aesthetic pedagogies critically and creatively communicate, teach, make meaning, uncover, and involve students in learning activities. While prevailing attention in the academy is placed on science, math, business, and technology, the collective aim of this volume is to highlight the imaginative practices and creative voices that address the potentials, tensions, and challenges that educators face in working through and within the confines of higher education (7). The editors, Clover and Sanford, draw on the expertise of educators from North America, Europe, and Africa who work in areas as diverse as religious conflict, civic engagement, teacher education, literacy, theater, museums, dance, and diversity training. The authors demonstrate through varied examples and commonly held convictions that arts-based methods, grounded in social relevance and educational theory, prepare and engage students to develop self understanding and attend to pressing political issues. The twelve, primarily co-authored, essays are organized into three sections: “Arts-based Teaching and Learning”; “Arts-based Research and Enquiry”; and “Community Cultural Engagement.” Part One begins with five chapters highlighting examples of arts-based teaching within university settings. Noting the weight placed on traditional assessment and evaluation, the ubiquity of text-based learning, and the stress on technical rationality at the expense of other ways of knowing, the authors convincingly illustrate how the arts provide alternative spaces for learning that can expand student learning rather than diminish it. Skills for engaged citizenship in connection with global and local debates are explored through shared art making, while music is examined as a mobilizing force for activism. Story drama facilitates embodied ways of learning and imaginative writing “turns the gaze” outward to help marginalized student “speak.” Arts-based pedagogies address real problems, help students ground concepts with their own lived experiences, and build communities of learners, while performance-based results synthesize knowledge. The three chapters in Part Two discuss how arts-based research, which makes use of the arts in the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data, provides researchers with a broader palette of investigative and communication tools with which to garner and relay a range of social meanings (82). For example, theater and drama action-based research is employed by university researchers to assess stress among staff within their work place. Doctoral candidates use collage to tap into extra-rational ways of knowing in order to enhance and clarify their research projects. Dissertation advisors act as midwives supporting the use of arts-based research demonstrating that it is both rigorous and evocative in that its purpose is often to raise consciousness and compel, rather than simply to convince or persuade. At the heart of arts-based inquiry is a radical politically-grounded statement about social justice and control over the production and dissemination of knowledge (81). Part Three explores community cultural engagement and the arts. Issues related to racism and diversity awareness in Canada, religious conflict in Northern Ireland, and lifelong learning and cultural engagement in a museum in Scotland are examined through arts-based methods. In these varied examples boundaries between academy and community, practitioners and experts, access and privilege, are diffused. Instead, the authors point to the benefits of working beyond disciplinary silos in order to dismantle elitism, classicism, and notions of art for art’s sake. This book is written for all who would like to work beyond normative structures of higher education by using creative arts-based methodologies and practices. It is for those who wish to collaborate with community artists and cultural institutions and for those who seek ways to unite affective and cognitive learning by engagement with and through the arts. As the editors assert, the arts have potential for augmenting the human aesthetic dimension, rupturing categories of how the world is seen, and imagining the world as it might be.

Service-learning, as a valued curricular support to learning, has received attention in institutions of higher education as an approach that provides students with social and academic capabilities for their future careers. The concept of service-learning has been around for centuries in the American academy, but higher education in Europe has not fully embraced service-learning as an innovative pedagogy to better prepare graduates for a global workforce. Research on service-learning has mainly focused on the benefits students receive, and how to organize service-learning to produce these benefits. Author Susan Deeley suggests “[moving] away from attempts to ‘prove [service-learning] works’ towards a more sustainable approach of improving how it works” (31). Critical Perspectives on Service-Learning in Higher Education offers a pioneering voice in the field of service-learning because the author practices what she preaches. She addresses the role of the teacher in service, offering practical strategies to facilitate critical reflection and academic writing, and tips for writing critical incidents and reflective journals to enable students’ “lifelong critical development” (8). The author constructs a theoretical paradigm with guidance on how to design, implement, and accomplish service-learning. Through the analysis of a theoretical perspective, Deeley offers multiple practical service-learning applications, including some from personal experience, both in local and international settings. The author does not intend to solve the critical need for innovation in teaching across the disciplines; rather, she offers learning theories, ideas, and perspectives for the regard of service-learning as a critical pedagogy that fosters agency and empowers students to explore on their own terms with guidance from faculty. Each chapter can stand alone or be used as a resource for teaching and learning. The book is divided into two major sections: (1) theory and (2) practice grounded in field experiences. In search of an inclusive view of service-learning, the first section (chapters 2 to 4) engages the reader in defining “service-learning” through a theoretical and philosophical lens, presenting an extant list of definitions and considerations that raise questions about service-learning’s “suitability” as a critical pedagogy. The second section (chapters 5 to 7) moves toward the practical application of service-learning “[which] involves students as active learners, constructing meaning in order to make sense of their experiences” (103). Students experience a “transformation” in the process of reflecting critically on their beliefs, opinions, and values. The research includes journal excerpts from eight students over the course of seven years showing how service-learning works in community settings. The importance of summative co-assessment is underscored for facilitating a democratic approach to learning that helps students master and articulate skills which are transferable to the workplace. While only three pedagogical theories are reviewed (traditional, progressive, and critical), the discussion provides an approach to enhance the scholarship of teaching (Boyer, Scholarship Reconsidered: Jossey-Bass, 1990). This approach is advanced by Deeley’s explanation of practices used in critical reflection. Even though the book was written from an international viewpoint, the service-learning experiences only take into account two countries: the United Kingdom and Thailand. Thus, additional approaches from around the world would enhance the global perspective. This book is an excellent resource that would benefit faculty members and administrators collaborating to integrate this “powerful pedagogy” as a complement to or replacement for traditional forms of teaching and learning.

At many institutions of higher education, tenure-track faculty positions are exclusively full-time positions, while part-time appointments are for contingent faculty only. Some schools, however, use job-sharing, joint appointments, phased retirement, and other modes to make part-time positions available for tenured and tenure-track faculty members. In Part-Time on the Tenure Track, Joan M. Herbers argues that part-time tenure-track models can benefit both faculty members and the institution. Through the first half of the book, Herbers gathers and analyzes both quantitative and qualitative data on existing part-time tenure-track (PTTT) faculty. These data show that PTTT faculty report higher levels of job satisfaction than their full-time counterparts. PTTT appointments are most common in medical schools, but there are currently eight thousand PTTT faculty across all institutions with tenure systems (5, 22). While flexibility for child-rearing and other family commitments is a common reason faculty seek out PTTT work, it is by no means the only one. Mid-career faculty may pursue consulting or other interests, late-career faculty may step down job obligations in preparation for retirement, and faculty at any stage can face medical crises or other temporary conditions that make PTTT work especially attractive. Most of the junior faculty in Herbers’ analysis eventually receive tenure and hold full-time appointments. In the second half of the book, Herbers advocates for the wider implementation of PTTT positions by addressing their benefits and challenges, providing policy recommendations, and proposing best practices. Herbers asserts that academia has long been driven by an “ideal worker” model that assumes faculty serious about their careers will work only full-time. Thus, along with the technical considerations of salary and benefits, teaching and research obligations, involvement in shared governance, and access to faculty development opportunities, faculty considering PTTT work must also reckon with cultural assumptions that privilege the full-time worker. Yet PTTT work provides welcome flexibility to faculty at various stages of life, including those who might otherwise resign their positions (91). Institutions receive the benefits of satisfied and often extraordinarily dedicated workers (91-92). The most vexing and still-unresolved problem acknowledged in the book is just what constitutes “part-time” work. Telling the story of her own job-sharing arrangement, Herbers recounts that she and her spouse each worked forty hours per week – the standard American full-time work week – in their half-time positions and received together 1.4 salaries (2). She found that schedule to be consistent with the other PTTT faculty she interviewed (100). To be sure, faculty work can be difficult to quantify, since faculty productivity is not usually measured in hours worked. Even so, PTTT positions may reduce compensation for faculty more than they reduce institutional obligations, a pitfall for workers that is both policy- and culture-driven. Part-Time on the Tenure Track is a succinct yet comprehensive look at a little-known model for faculty work. The book will be an especially helpful resource to administrators who write policies and negotiate contracts, as well as to faculty members who may be considering part-time appointments.

Entering his career as a high-flying yet narrowly trained graduate researcher in astronomy, Aveni’s engagement with students in his discipline and in the interdisciplinary context of liberal arts education has seen his own research flourish -- as indicated by his full title as Russell Colgate Distinguished Professor of Astronomy, Anthropology, and Native American Studies at Colgate University. That this flourishing has been driven by continually seeking ways to entice his students to enjoy and collaborate in learning and research, rather than by dint of solely private endeavor against the grain of his teaching commitments, is marvelously set out in his tales of fieldtrips, flunked comet observations, and explosive co-teaching assignments. Teachers of religion and theology may find themselves under increasing pressure to justify their place in the liberal arts context. Aveni shows clearly how imagination and good teaching practices can both competitively enhance a discipline’s standing and co-operatively benefit collegial efforts in other areas. My particular interest in the book arises from the challenge of leading general education redesign efforts at an institution where religion and theology are deeply cherished. I have needed to imagine how other disciplines can enrich my teaching of theology as integral to a liberal arts education. Aveni, with a lifetime of experience, has been helpful both practically and philosophically as I approach my local task. For example, where we emphasize interdisciplinary integration with some co-teaching and team teaching, Aveni looks at those arrangements as more beneficial when disintegrative – that is, when conflict between teachers generates a learning opportunity for students. Those not yet inducted to the professional discourse on general education and the liberal arts will find this text a winsome entry, shorn as it is of the social science research-speak that can clog the fluency of that vital conversation. Aveni is a dedicated practitioner, demonstrating in his own prose the liberal arts skills that should be demanded even of those in STEM. Aveni questions the commodification of education in his last full chapter: “Education just isn’t a commodity, and I don’t think students in the midst of a classroom experience can fully judge its value” (175). He is, at the same time, also able to take the long view on teaching evaluations to recognize their relative worth. He is not a traditionalist in the sense of insisting on a classical western canon, claiming that its proponents, such as Allan Bloom, are “many whose backgrounds demonstrate a profound lack of inquiry into cultural ideals other than their own” (183). Readers will be rewarded with this kind of punchy delivery that invites learning by agreement or disagreement, but not through over-complication and obfuscation. Aveni writes as a generous peer. He is quick to recognize the importance of senior mentors, alongside mundane realities of budgetary constraints, innovative grant-seeking, and teaching driven by research. Throughout, the author’s wit and humor stand out, but readers will be struck most of all by his care for his students.

This book contains an introduction by the editors and eleven papers from the Consortium of Higher Education Researchers (CHER) conference in Lausanne in September, 2014. The first five papers address arguments over the rationales for public funding of higher education, especially in current political contexts: “How Do University, Higher Education and Research Contribute to Societal Well-being?” by Michèle Lamont, “A Persian Grandee in Lausanne” by Sheldon Rothblatt, “A New Social Contract for Higher Education?” by Peter Maassen, “Higher Education and Public Good: A Global Study” by Simon Marginson, and “Defending Knowledge as the Public Good of Higher Education” by Joanna Williams. The remaining six papers focus on regional or national developments: “Partisan Politics in Higher Education Policy: How Does the Left-Right Divide of Political Parties Matter in Higher Education Policy in Western Europe?” by Jens Jungblut, “Access Equity and Regional Development: a Norwegian Tale” by Rómulo Pinheiro, “Shrinking Higher Education Systems: Portugal, Figures, and Policies” by Madalena Fonseca, Sara Encarnação, and Elsa Justino, “Pathways to Higher Education in France and Switzerland: Do Vocational Tracks Faciliate Access to Higher Education for Immigrant Students?” by Jake Murdoch, Christine Guégnard, Maarten Koomen, Christian Imdorf, and Sandra Hupka-Brunner, “The Development of the Québec Higher Education System: Why At-risk College Students Remain a Political Priority” by France Picard, Pierre Canisius Kamanzi, and Julie Labrosse, and “Engineering Access to Higher Education through Higher Education Fairs” by Agnès Van Zanten and Amélia Legavre. The editors ground the collection in social contract theory, specifically the claim that higher education should foster equality of opportunity (2). Many of the chapters discuss how that goal is being problematized and privatized by political pressure to emphasize education’s economic benefits to individuals and society in a knowledge-based economy in place of other kinds of personal and public goods, such as an informed citizenry. These political shifts have the effect of calling peer review into question as the standard for evaluating academic research because different generations of researchers may emphasize different standards and measures of performance, and because public managers impose their own criteria (13). These articles document some paradoxical developments, such as declining student demand for science and engineering courses in some countries (139). They also illustrate how the increasing internationalization of higher education standards, through processes internal to the European Union and also due to the rising prominence of international rankings, puts disproportionate pressure on humanistic disciplines that tend to emphasize national or regional topics (12). Higher Education in Societies provides an important reminder of the crucial role of national politics in formulating the goals and ideals, as well as the funding, of higher education. For this reader, it highlights by omission the unusual situation of American academics like myself who work for private colleges and universities, which disproportionately dominate the teaching of theology and religion in the U.S. (A complementary discussion of theology and religious studies in European universities appears now in Christoph Uehlinger’s “Is the Critical, Academic Study of the Bible Inextricably Bound to the Destinies of Theology,” in Open-Mindedness in the Bible and Beyond [Korpel and Grabbe: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2015], 287-302).

The articles in this anthology seek to establish both theoretical boundaries and practical guidelines for feminist practice in the classroom. The essays are, on the whole, very successful in regard to the first goal; however, this reviewer wishes there was more in the way of concrete advice, assignment structure, or assessment design throughout. Every essay in this collection clearly shares a passion for feminist pedagogy. Throughout, the authors share a clear understanding of feminist methodology and praxis and make clear their desires to transform and invigorate classroom experience through this knowledge and experience. In one of the more powerful examples of theory influencing the classroom, Jennifer Browdy de Herndandez discusses the ways in which Gloria Anzaldua’s concept of conocimiento (“awareness” or “knowledge”) is foundational to her course “African Women Writing Resistance.” While this work stands out in its clear discussion of feminist principles as foundational for teaching, each essay in the volume displays clear grounding in both feminist theory and pedagogical research. The editors are to be lauded for finding such a diverse group of authors with such uniformly strong methodological knowledge. However, the volume faltered in two ways. First, the discussion of method and theory, while a strength in many ways, became repetitive over the course of fifteen chapters and an introduction. It might have served the anthology better to have a methodological section toward the beginning of the volume that set the tone for the work as a whole. Application, course design, and even assessment sections that drew on the work of the previous scholars could have followed the preliminary discussion. Instead, the various contributors repeat many of the same methodological and theoretical preoccupations throughout: decentering, contextualizing, intersectionality, gender performance, and so forth. For those who read the volume beginning to end, this recitation of method and theory becomes unnecessarily repetitive. Second, this reviewer found the volume lacking in practical approaches to the classroom, particularly regarding assignment design and discussion processes. Several chapters mention the classroom, but few authors share their actual day-to-day work, assignments, or assessment data. For example, in the initially fascinating essay on a non-credit outreach humanities course (“Rethinking ‘Students These Days’: Feminist Pedagogy and the Construction of Students”) the authors spend the majority of the discussion on the social location and needs of the participants. This is crucial information, to be sure, and welcomed by the reader. However, when it came to the class itself the authors offer no observations about discussion practices, relevant assignments, or course assessment. The reader was left to wonder: how do they achieve such positive results? And how could I, with similar students, replicate their achievements? Many of the other essays similarly offer no discussion of the course or courses as they were practiced; instead, authors employ vague language about discussions, stakeholders, or their experiences of the course as a whole. From the perspective of a reader, and fellow feminist teacher, I was left at a loss as to how to change my courses now to enact in the classroom the strong methodological framework displayed throughout this volume in any practical way. The clear exception, in regard to practical advice for transforming assignment design and assessment, was the chapter by Linda Briskin, “Activist Feminist Pedagogies: Privileging Agency in Troubled Times.” This essay emphasizes the importance of moving from a “caring for” or charity model of service learning to a community-based model. The theoretical framework here is spot-on, emphasizing context and avoiding the patriarchal and colonialist subtext of charity-focused work. However, Briskin also includes three sets of inserts for extra information concerning writing assignments and questions from the course and follows these with a potential model for analysis of these assignments to show student learning. As a teacher, I learned more from this chapter – and certainly more that I can put into immediate practice – than from any other work in the volume. The discipline of feminist pedagogy, in both its theoretical and practical forms, is a promising horizon for transforming and liberating higher education classrooms. While this volume did not offer as many practical tools as it might have, the reviewer was heartened to read of the broad support and sophisticated theoretical grounding in feminist pedagogy from among its authorship.

David Greene’s Unfit to Be a Slave sets out to address the role that education should play in society. His argument rests on the assumption that current educational opportunities are limiting or exploitive of adult working students. He says, “today, the corporations and financiers benefit from the ignorance and silence of the population. The less information and understanding people have, the more they can be misled and controlled” (71; this criticism is borne out in more detail in chapters 4 and 5). The current trend towards “job skills education” is elicited as a prime example of inadequate higher educational opportunities which serve the interests of corporations and not students. Greene argues that “the duty of an educator is to broaden the horizons of learning and challenge the limitations they [students] face” (53). Thus, for Greene, successful education arrives at the “maximal development of intellect, understanding, culture, and awareness of the world around us” (9). Further, effective education must aim to develop students as leaders, and empower them for success, rather than giving them only skills requisite for low-wage or menial employment. In an effort to ameliorate these problems, Greene presents an outline of a pedagogical system built on Paulo Freire’s idea of “problem posing education.” This model starts with the dissolution of customary boundaries between teacher and student, recognizing that both students and teachers need to learn, and both can teach. Greene builds on this model, advocating that education ought to be focused on the collective development of a set of central literacies: functional literacy, civic or political literacy, health literacy, environmental literacy, and financial and economic literacy (22). Each of these literacies includes competencies for both individual and corporate ends, and Greene’s argument posits they can be gained through what he calls “central tools,” which are: listening, the recognition of pre-existing student knowledge, discussions about real problems faced in daily life, and the advocation and organization of specific actions to combat those problems (71-77). Greene also strongly suggests that education not be confined to the classroom. He contends that higher education must empower students to change society and he provides examples from his own teaching that underscore this need. Unfit to Be a Slave does not contain any quick fix techniques to import into your classroom to move towards a more effective classroom experience, rather it presents an idea of education that is much broader and more holistic. Throughout the book Greene strives to promote a broad educational model that is directed not to the acquisition of job skills themselves, but to an increased ability of students to function well in society and to live well. The book focuses on the plight of adult workers, and takes particular pains to explain the oppressive economic and social factors working against the thriving of adults in the workforce. Personal politics aside, faculty are reminded that life exists outside of the ivory tower of academia, and that student experience informs their perspectives on theoretical matters, and can be marshaled as an asset to an effective learning experience for both the instructor of record and the students enrolled in the course.

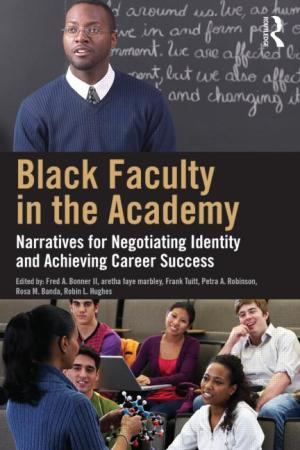

The editors and selected contributors provide cogent insights on navigating academic environments as faculty of color. Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a conceptual and methodological lens to identify issues of racial incongruity (1). The strength of this volume of 13 chapters is the use of first-person Scholarly Personal Narratives (SPN) by contributing black scholars to analyze particular experiences and modes for survival, if not reform in educational institutions (3). In the introduction, editors Truitt and Bonner review the evolution of CRT to conceptualize “core thematic trends” (4) that collectively structure the narrative content and divide the volume into three parts. Part 1 is titled “Black Faculty: Navigating Daily Encounters with Racism.” Chapters 2 through 5 are narratives on interpersonal experiences in institutional climates. In chapter 2, Giles details CRT to analyze presumptive behaviors encountered since his formative years to his current professorial appointment. Moore focuses on racial microaggressions in chapter 3 (24) to note environmental similarities of his upbringing in a predominately white community and his exposure to social systems in the work environment at a predominately white academy. Lewis co-authors chapter 4 to highlight “insider-outsider experiences” (33) as a British black man, while Helm highlights her duality in America as black female navigating racialized gender stereotypes that undermine professional credibility (35). In chapter 5, Shavers, Butler, and Moore cite “cultural taxation” (42), a phenomena of commodification risks for underrepresented black faculty confounded by excessive service project requirements as token institutional representatives. In Part II, “Black Faculty, Meaning Making through Interdisciplinary and Intersectional Approaches,” chapters 6 through 9 offer multidisciplinary intersectional approaches to recognize formal institutional rules and navigate informal expectations. Five contributors to chapter 6 – marbley, Rouson, Li, Huang, and Taylor – use a multiple theoretical lens to assess microaggression in performance-compliance to diversity expectations, parity of scholarship praxis, and tenure requirements. Croom and Patton overlay “critical race feminism” (66) onto CRT analysis in chapter 7 to identify dynamics that black female academicians encounter from black and white colleagues. Similarly, in chapter 8, Andrews details institutional macroaggressions and interpersonal microaggressions (80) that hinder female scholars’ inclusion in tenure-track aspirations unless support of professional identity and authenticity is cultivated. Stewart shares nuanced sexuality challenges in chapter 9 as an “outsider-within” (95) where her triadic identities, black, female, and queer are stereotyped tropes for discrimination and invisibility in the academy. Finally, Part III, “Back Faculty, Finding Strength through Critical Mentoring of Relationships” includes that focus on mentor relationships as supportive modes of self-reflection and networking. In chapter 10, Flowers relays a critical need for candid self-reflection with trusted allies as mentors outside institutions if not found within. Smith asserts in chapter 11 that tenure does not guarantee collegial inclusion, respect, or appointment to leading roles; still, attentiveness to self-esteem, persona perceptions, and cultivating allied mentors helps to build critical social capital (117). Finally, chapters 12 and 13 focus on developing mentor relationships with students as Bonner recalls mentor influences as a student that inform his thematic roles as a faculty mentor to students (123). In the final chapter, Tomlinson-Clarke also urges faculty-student relationship with relational mentoring lessons as a graduate student in a historically black college (HBCU) and as a doctoral student in a predominately white university (PWI). In summary, Black Faculty in the Academy is not a prescriptive behavioral guide of dos and don’ts; rather, the diverse analyses of lived experiences with recommendations provide avenues for readers to construct reflective assessment of present individualized situations. As an African American professor, I resonated with the narratives as discernment tools for success. The book also provides a starting point for collective institutional discourse; however, in my opinion, the volume would benefit from a section of narratives by non-black faculty who acknowledge critical race theory issues that require discourse in institutional settings where non-black colleagues might otherwise be defensive to the critique of the book’s black contributors. Nevertheless, for new faculty of color as the likely primary readers, this volume offers powerful insights of CRT to raise awareness and encourage development of contextual navigation strategies.