Blogs

I have been a consultant for the Wabash Center for more than a decade now, and I still often wonder what I am supposed to be doing when I consult, and how I should be doing it. Supporting colleagues in the intimate and courageous act of opening up their teaching to other colleagues’ input is often an uncharted journey. I think it’s even more challenging in an era where the primary pandemic I worry about is the one having to do with discerning what is true and real, and what is not. I think you can talk about this in any number of ways—COVID-19, racial injustice, climate catastrophe—but at heart the question is how we navigate the complex and multiple realities we and our students are inhabiting. I have had the enormous privilege of walking alongside two gifted colleagues these past few months—Dr. Mitzi Smith and Dr. Dan Ulrich—as they took on the challenges of designing and leading a course together, where one of them was the expert and the other was the learner, all the while walking alongside their student learners. Drs. Smith and Ulrich are Second/New Testament scholars, teaching in two very different seminary contexts. Dr. Smith is an African American woman, and Dr. Ulrich is a white man. This last sentence is at the heart of the project they took on, within the Wabash Center’s grant program, to imagine and embody what it can mean to develop a pedagogically effective and ethically responsible trans‐contextual online intensive course. They set out to bring into focus African American and womanist approaches to sacred texts—both those of the Bible, and those of the lives of women and men whose struggles are part and parcel of having no permanent shelter. Dr. Smith was the formal teacher, Dr. Ulrich the formal learner. And I was a listener, a learner, and perhaps a cheerleader as they tried to walk this walk. I think I know a lot when it comes to designing learning in digital spaces—but much of what I know is not relevant when trauma is the essential ecology in which we are living. Here are things I learned: Teaching and learning are thoroughly relational, and this moment in time requires us to face that reality directly and intentionally—it is no longer possible to pretend that what we do is purely cognitive. It’s really difficult to be trained as an expert in your discipline, and from that training demonstrate being an active learner. Humility and openness are key to navigating this terrain, but they are rarely the skills or capacities we are rewarded for in our scholarship. Empathy, not sympathy, is essential in this work but the difference between these two abilities is not generally taught in higher education. Certainly our students find the distinctions very difficult to parse. Structural and systemic racism are so much a part of higher education that it takes a lot of effort simply to discern the “next right step” in resisting them. Teaching together needs to begin in relationship-building long before a syllabus is written, let alone implemented. There is a necessary balance to be found between the improvisational nature of teaching when you are doing it alone, and the shared work of collaborative pedagogical design. Institutional constraints will force certain problematic compromises to be made no matter how committed you are to justice. Here are questions I still have: What kind of authority is it necessary to have in a class? With a colleague? As a consultant? How do you say “I’m sorry” in a way that matters? What does it mean to be an “expert” in an academy so riddled with injustice that the very performance of “expertise” may be re-inscribing that injustice? What degree of transparency is important for students gaining a sense of the power dynamics embedded in specific academic disciplines, and when might it be better to obscure them? I am left with a profound gratitude that there are scholars in this world who are seeking to break down some of the power dynamics of the academy. I remain thoroughly committed to the search for a “pedagogically effective and ethically responsible trans‐contextual” way of teaching even if I’m still not sure what that looks like—at least this project has offered me a hopeful glimpse!

The first religion course I took in college was an introduction to the Bible, one of two required religion courses in our core curriculum. The students’ reaction to the course follows what, I suspect, is familiar terrain for those who teach similar courses. The application of academic tools to the study of their sacred text was, for many students, unsettling; for some, inappropriate and heretical; and, for others, “meh” -- that is, not even curious as to why this tension might show something about their lives or the world we inhabit. I am reminded of that experience each time I teach our required service-learning course. The use of critical academic tools to examine acts of kindness, charity, and compassion is experienced by students as unsettling, inappropriate, political… despite the fact that, like the introduction to the Bible course, this critical approach to service is not new. With the changing religious landscape shaping the experiences of incoming students as well as the diminished place of religion courses in many university curricula, courses involving service-learning may increasingly become the primary sites for introducing critical theories to deconstruct problematic notions of ethical action in the world. The service-learning course I teach most often involves a short-term study abroad component in South Africa. For our students, everything about that course is new; and, as is so often the case, my passion for the topic and the transformative potential of the experience results in an overstuffed bag of history, social theory, religious studies, contemporary politics, peace and reconciliation studies, global health, music, and, somewhere in there global service learning – or, as freshly minted clergy know it as: trying to preach the whole of the Bible in your first sermon. One of the primary methods of assessment typical in these courses is reflective journaling, both prior to and during the trip. It affords an opportunity to see the students’ integration of course materials and their expectations and experiences. These journals also serve to focus evening debriefs while traveling – a kind of focus neither I nor the students are able to achieve during the fragmented nature of a full course load on campus. What do these reflective, real-time reflections consistently reveal? Many students struggle with their newly acquired critical perspective on service, especially when pressed on the (in)appropriateness of doing short-term service learning with children from other countries. The conceptual frame of white/western savior throws into turmoil service identities that have been formed throughout childhood and reinforced by the accumulation of a kind of social capital that finds purchasing power on college applications. (Is it surprising that students who have spent years curating a college resume to cater to our institutions’ premium on volunteering and quantifiable service hours find critical examination of service disorienting?) I have tried a variety of strategies intended to hold together processes of learning and unlearning, or at a minimum suspending one’s previous learning long enough to consider a new perspective. The goal in these strategies is to induce experiences constructive cognitive dissonance and creative disruption, without inducing irreparable irruption. Some strategies, like the use of satire, I test out with trepidation, aware that my own appreciation for the poignancy of the satirical critique draws deeply from an academic literature that remains opaque to the students. (In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, videos by the group Radi-Aid have made consistent cameos in my classes, serving as conversation starters. They also remind me of how problematic, yet persistent cultural tropes about Africa and famine from my childhood in the ‘80s that pricked my conscience then can be critically examined now in ways that re-center the agency of persons who were the objects of international displays of pity.) Other strategies include the move from general reflection to more structured, guided journal entries that invites students to engage directly and critically with their assumptions about volunteering and service abroad; required completion of an in-depth, case study based ethical volunteer module prior to the trip; and, a class blog visible to the wider campus and the students’ networks of support. It is this last one that I have found particularly effective. The semi-public blog, though a lot of work on the trip itself to update – especially when wifi accessibility is variable – has been a new venture for me. As an assignment, I have found it especially helpful in foregrounding questions of representation in ways that student journals and papers do not. Its publicity demands additional reflection on the part of the students and, since they are required to work with me in revising the blog before posting, it provides an opening for a focused conversation about how subtle (and not-so-subtle) colonial and racial frames inform our efforts to depict the lives of others. A lot has been written in recent years about the problematic posting of photos and videos from service trips and their role in reinforcing stereotypes and savior complexes or legitimizing selfie culture as some kind of proxy for service – standard fare now for orientations sessions prior to travel. However, the blog format reminds me that we should be encouraging through our assignments a similar degree of self-awareness in our non-visual (or textual) depictions of service learning. To be sure, not every student comes out the other side of the blog conversation “converted” to a more critically aware approach to service. The decisions they make in conversation with me about what to include in the public-facing blog likely mask the degree to which students’ beliefs about service-learning or the appropriateness of selfies with children “served” remain unresolved. As with so much of what we set out to do in our courses, the introduction of new conceptual frameworks and the accumulation of evidence is not a guarantee of scales falling from students’ eyes. I do take some solace in coming across phrases in journals and spoken aloud in debriefs such as “I had never really thought of … but now…” Such acknowledgments serve as a reminder for me of my own personal path towards critical service-learning, a path that started unsurprisingly, perhaps, with what I would now characterize as problematic encounters, that is, with experiences of serving “others,” and only later – much later, often – with theory. Perhaps this is what a learning as praxis extended over time feels like.

Giving constructive feedback to students is one of the most powerful pedagogical functions a teacher can provide for learners. Yet, teachers often are reluctant to provide feedback for various reasons, like the fear of coming across as critical or the risk of hurting someone’s feelings. But the fact is that good learners crave teacher feedback—even in the form of challenge for deeper thinking. Constructive instructor feedback in an online course helps promote and maintain student engagement. The following four-step approach to effective feedback can make for an efficient “formula” for providing feedback without getting overwhelmed. Additionally, instructors can offer this four-step approach as the standard practice for students’ own feedback responses in discussion forums. Here is a four-step process for giving constructive feedback in an online class (this works just as well in a classroom context). A Four-Step Approach to Constructive Feedback Step 1: Clarify The first step in this feedback procedure is the question of clarification. These are questions that can be answered with very brief responses. They do not raise substantive or philosophical issues, and they are not judgmental. They are merely a way to establish that you heard and understood what was said and/or meant and get clear on important details that affect understanding. Asking students to clarify their responses helps them take responsibility for their thinking and for their answers. It also helps them correct vagueness and to clarify their own initial thinking and “go deeper.” Examples: “Did you mean to say…?” “How are you using the term ___. Can you provide a definition?” “When you said x, did you mean y?” “Was it a sophomore class?” “Were you the only teacher?” “Was this at the start of the year?” “How long was this unit?” “Can you give an example?” Step 2: Value Next, state what you value in the student’s effort or response. Too often, we skip this step and go right onto points of contention, assuming people know we appreciate their engagement and effort in responding. But it’s amazing how much everyone needs affirmation that their efforts are heard and appreciated. Tell the student what makes sense, what seems inspired, what aligns with your own perceptions and experience, what informs your own thinking. Or simply acknowledge a good effort. This sets up a great foundation from which to deal with the (often minor, but sometimes large) points of disagreement or challenges to deeper or more responsible thinking. Step 3: Challenge At the third step, get into those ideas that you want your students to wonder about or wrestle with. This is a good time to use techniques like using “I-messages” (“When you talk about doing x, I think about…” or “When I’ve done x in the past, students have…”) or raising questions by wondering rather than pronouncing judgments (“I wonder if x would happen when I did y,” or “When you suggested x, I wondered if it might…” or “What do you think would happen if…”). This is the phase for honest, constructive concerns, and, at the same time, for delicacy. If we establish a culture of respectful questioning and a challenge for learning that makes it clear that reasonable people can disagree and differences in contexts really do make different solutions effective, such a climate can keep conversation going. Staying in conversation means we help students learn how be able to understand each other better over time. Step 4: Suggestions for Deeper Thinking/Exploration Finally, after exploring the questions that arise in response to someone’s work, we can offer suggestions for deeper engagement. For example: “From our perspective, and the limited view we have of the complexity of the situation, I wonder if [suggestion] would make a difference?” “Once I tried [some suggested solution] in a similar situation, and z happened.” “I’ve heard of someone doing [a suggestion] in the face of such challenges, and I was so inspired by that idea!” “What if you [a suggestion]?” “I wonder if you’ve tried [a suggestion]?” Adding “...what do you think?” to these types of questions invites a response for deeper engagement. The key here is staying genuinely open to the possibility that you don’t know what’s best for this situation, but that you hope you’ll be able to offer something helpful, some bit of insight that might make sense in the complexity of the question or dilemma the person is managing or attempting to address. Adapted from an online course from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, WIDE Program.

In Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, James W. Loewen finds several problems with how slavery is taught in high schools across the United States. Loewen observes that white Americans remain perpetually startled at slavery. Even many years after high school, white adults are aghast when confronted with the horror and pervasiveness of slavery in the American past. It seems they did not learn, or have quickly forgotten, that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were among the multitudes of white Americans who owned enslaved Black Americans as their human property. Loewen surmises the ignorance of white Americans on slavery can be traced back to high school classrooms. History textbooks incorrectly present slavery as an uncaused tragedy and minimize white complicity in the enslavement of Black Americans. Students are meant to feel sadness for the plight of four million enslaved Black persons in 1860, but not anger toward the approximately 390,000 white slaveowners because these slaveowners, and their unjust actions, do not appear in the pages of the textbooks. Since Loewen published his book in 1995, there have been strides to improve the teaching and learning on slavery. One notable example is the introduction of lesson plans based on the 1619 Project from the New York Times in middle and high school classrooms in Baltimore, Buffalo, Chicago, Newark, Washington, D.C., and other cities. Yet, the backlash against a more comprehensive curriculum on slavery, which is most visible in President Trump’s recent call for a “1776 Commission” to directly challenge the pedagogy of the 1619 Project, reveals the need for an assessment of how theological schools are engaging these educational debates around slavery. As I reflect on my experiences as a theological student and educator, I am concerned seminary classrooms are also failing to provide instruction that properly captures the totality of white Christian involvement in slavery and anti-Black racism. The perpetual shock in some white congregations over some basic historical facts about slavery is alarming. One pernicious myth I encounter is the notion that most white Christians in the antebellum period were abolitionists pushing for the immediate emancipation of enslaved Black persons. This is simply not true. Very few white Christians held this position and there was little support for immediate emancipation in the Baptist, Episcopalian, Methodist, and Presbyterian denominations. Many white Christians in the southern states defended slavery so vigorously that some Black and white abolitionists identified white churches as the most impenetrable strongholds against their cause. Benjamin Morgan Palmer, a white Presbyterian pastor in New Orleans who previously taught at Columbia Theological Seminary, preached in 1860 that slavery was a providential trust that whites must preserve and perpetuate because the natural condition of Black Americans was servitude. Palmer mocked northern abolitionists for thinking that Black Americans could survive alongside whites as equals. Palmer was neither reviled nor rebuked for his white supremacist views. Rather, he was widely celebrated and elected to serve as the first moderator of the newly formed Presbyterian Church of the Confederate States of America in 1861. Black Christians like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth emphasized the eradication of anti-Black racism as an essential component in their abolitionism. But even white Christian abolitionists in the northern states fell woefully short in their advocacy against anti-Black racism. Archibald Alexander, a white theologian and professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, endorsed the colonization movement to send free Black Americans to Liberia, because he felt the discriminatory contempt white Christians held against Black Americans was too insurmountable to overcome. In 1846, Alexander wrote that anti-Black racism was wrong and unreasonable, but he did not commit to working toward racial equality. Instead of teaching white Christians to repent of their racism and white supremacy, Alexander preferred Black Americans, once emancipated, leave the country and find another home where their skin color would not be despised. Seminary classrooms may not treat slavery as an uncaused tragedy, but I believe some of our teaching and learning in theological education also minimizes white Christian complicity and misdirects the anger students should feel about slavery. Rather than fully grappling with the histories and legacies of economic exploitation, sexual violence, and virulent anti-Black racism perpetrated by white American Christians, students are left with a neatly packaged lesson on slavery centered on the dangers of deficient biblical interpretation and proof-texting the Scriptures. Such instruction misses a crucial point the abolitionists themselves made, which was to identify and confront the anti-Black racism of white Christians. In 1845, Frederick Douglass differentiated between genuine Christianity and the “corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land” in his autobiographical narrative. In the ongoing pursuit of racial justice today, our seminary classrooms must also engage in teaching a more complete history of slavery and white American Christianity.

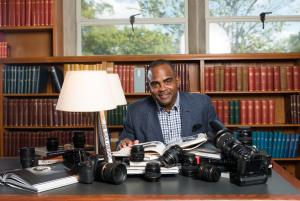

On Wednesday, October 7, 2020 we had our first gathering with Victor Wooten and the fifteen scholars who are privileged to be a part of this cohort. Victor asked us, “Why are you here?” Many answered while I listened. I didn’t speak during the formal two hour period, I listened. I hadn’t intended not to speak. Prior to the gathering formally beginning I was my normal raucous self but when Dr. Lynne Westfield called us to order my posture changed. If would’ve answered the question Victor posed I would’ve said: “I am here because I love music. I am here because I use music in all of my classes. I am here because I thank improvisation is the key to living full and adventurous life. I love the guitar. I love the bass. I am grew up listening to Larry Graham, Bootsy Collins, James Jamerson, Jaco Pastorious and so many more. I am a true fan of Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miler, Chritian McBride and Victor Wooten. Victor Wooten is not simply a musician but to me he is a mystic, a teacher, a scholar and brilliant. Whenever Victor Wooten is in town I am there to be a part of the experience.” Everytime Victor comes to Atlanta I am there (the links below are to photo galleries of two of my recent experiences at a Victor Wooten concert). Victor Wooten at the Variety Playhouse in Atlanta, GA https://flic.kr/s/aHskZV22bG https://flic.kr/s/aHskzJKr6A I was in this cohort for the experience. I wanted to experience what it meant to be with Victor and my colleagues to do this work together, to grow together and reimagine what teaching could be for us in the present age. [embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GONEnFyj73w[/embedyt]

The first time I taught Interfaith Justice and Peacemaking, a class that explores interfaith efforts to create a more just and peaceful world, I began the class by discussing terms. What is justice? What is peace? I gave students quotes to read from various figures in American society and asked them to reflect on these famous persons’ notions of justice. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” and Cornell West’s “Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public” were some of the quotes that made it onto the strips of paper I passed out to students. The exercise worked fine but it did not invite the kind of openness I was hoping for. It didn’t give students insight into how our various life experiences inform our understanding of what is just and unjust. A year later, I tried a different approach. I printed out results from an image search of the word “justice” on Google. I settled on five interesting, although imperfectly representative, black and white images: a raised fist, a gavel, lady justice with scales, a silhouette of a crowd of people with mouths exclaiming, and an image of children watering a tree. I created five desk stations and placed an image in the center of each one. I invited students to sit together facing one another in groups of three to four at each station and to freewrite about how the images made them feel—their gut reactions, emotions and memories stirred, and further images that came to mind. Then, I invited them to share their feelings and experiences with the other students at their station. Once everyone had a chance to share, they were encouraged to reflect on how, if at all, these images squared with their own senses of the word “justice.” This time, students opened up in ways that surprised me. They shared stories of positive and negative encounters with the police; stories of being treated fairly (and unfairly) by teachers; and discrimination they faced in their hometowns and at Regis. They brought up volunteerism, breaking the law, and efforts to change the law. And upon hearing the stories of their classmates, at least one student responded by saying, “I never thought of justice that way before.” The conversation that emerged framed justice as something more than retribution and in contexts as diverse as students own backgrounds. Genuine listening occurred between a group of students who included first- and second-generation migrants to the US from Mexico and Iran, an international student, an army vet and mother of two, feminists, atheists, Protestants, Catholics, and a Muslim-raised but Buddhist-leaning environmentalist, to name a few. In short, they discussed justice from all the angles I had wanted to teach them about. Students have a lot to teach one another. Though it’s easy to forget, the collective knowledge of the classroom in terms of personal experience and wisdom is often richer, more diverse, and potentially more transformative than my framing of a topic alone. Many of my students know all too well what it feels like to be a victim of an injustice. When given an opportunity to share these insights with one another, they arrive at a broader and more personalized understanding of justice than can be represented by a few famous figures’ quotes. This collective understanding is foundational to their ability to work together across lines of difference to build a more just and peaceful society. But creating an inclusive classroom environment where a diverse group of students can share with and learn from one another is not easy. Last week, in a writing seminar, as part of an assignment geared toward helping students avoid hurtful essentialisms in their writing, I gave students a writing prompt in which they were to reflect on an experience when they felt misunderstood because of their race, gender, faith, sexual orientation, country of origin, or economic status. One student, from Vietnam, wrote about her experience being accosted in a Walmart shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. A middle-aged white man came up from behind her and yelled at her for bringing the virus to the US from China. Shaking, and thus still physically bearing the wounds from this emotional trauma, she described to us the various cultures of Asia, and how it felt to be lumped together with people from forty-eight different countries, and blamed for a virus she did not create. Another student in the class, a white student from Kentucky, shared his experience of being called a racist because of an emoji he shared with a friend. “She thought I was being racist and I wasn’t! My best friends are Mexican and black. I chose the Latinx fist bump emoji because I like it. But I didn’t care. I didn’t let it get to me.” Everything about his body language—his shaking voice and red cheeks—betrayed the fact that it did get to him. These two students’ stories, the juxtaposed narratives of the one—a victim of racism, with the other—a person accused of racism, were pregnant with teachable moments. I listened to both, even tried to pause and slow down. Still, I failed to think of the right questions to ask in the moment. “How did that make you feel?” was all I could muster. In reflecting on what transpired, I’ve come to realize that while I appreciated both students’ willingness to share, something about his story directly following hers felt misplaced to me. While the student from Kentucky’s story mattered, and has much to teach us, it was in no way on par with the Vietnamese student’s story. They were not equal victims. Being blamed for bringing COVID-19 to the US because one appears to be of Asian origin is a far heavier burden to bear than being questioned about one’s use of a Latinx-looking fist bump emoji, especially when considering our country’s history of racism against Asian Americans. Moreover, I had asked students to write about an experience when they felt misunderstood because of their race, gender, faith, sexual orientation, country of origin, or economic status. Did the white student’s story of being accused of racism qualify? In “Pedagogies in the Flesh: Building an Anti-Racist Decolonized Classroom,” Karen Buenavista Hanna proposes a model of classroom dialogue that disrupts the conventional free-market models. In engaging with prompts or readings related to racism or sexism or any other kind of institutionalized oppression or injustice, she recommends that students be permitted to share only stories that happened to them, not stories that happened to a friend or someone they know. What this set of discussion parameters does is upend the normal colonial-based hierarchies of the classroom. It forces those who are used to speaking to listen and gives those who are used to listening a chance to speak, which begs the question, did I fail my students by giving them a prompt for which not every student had a response? Should I have reworded the prompt to say, write about an experience when you were misunderstood because of your race, gender, sexual orientation, or economic status OR if you don’t have such story, save your blank paper for notetaking in the conversation that follows? There are no easy ways to have an interfaith conversation on the topic of justice (and injustice). There’s no exercise or prompt that works all the time, and no set of fail-proof directives for the teacher-facilitator. The beauty of the interfaith classroom is that every person adds uniquely to the dynamic of the classroom. This is also the challenge. What I do know is that facilitating dialogue across lines of difference requires the acknowledgement that we’re not all equals—we can’t all contribute equally to every conversation on racism or other kinds of systemic injustice. Next time I ask students to write about being misunderstood, I might set up the conversation a little differently: “Write about an experience when you were misunderstood because of your race, gender, sexual orientation, or national origin and/or write about an experience when you were accused of being racist, sexist, or prejudiced in any kind of way. We’ll hear from everyone, but let’s give those who responded to the former set of questions a chance to speak first. Then, we’ll consider how all of us might be hurt by racist and essentialist thinking even if such thinking hurts some more than others.” I owed it both of my students—the one from Vietnam and the one from Kentucky—to help them unpack their stories. I wish I had asked the student from Kentucky, “How did that make you feel?” followed by “Why do you think your friend felt hurt by the emoji you sent?” I think he is brave enough to receive those questions. Or maybe I could have invited my students to pose compassionate questions to their classmates from Vietnam and Kentucky? Maybe their inquiries might have led us to an epiphany about justice I have yet to even imagine.

We are early into this novel and challenging COVID semester and starting to get feedback on the (for many) new modes of teaching and learning—namely, online/virtual experiences. One message from students is that they are feeling overwhelmed with keeping up or “figuring out” the LMS or the online course. I’m sympathetic. . . somewhat. Student reports of feeling overwhelmed is not new; some may say it’s a defining characteristic of students. I remember the response from so many of my professors: “You think you’re busy now, wait till you start working in the real world.” Admittedly, they were right. I suspect part of the problem of students feeling overwhelmed is the result of online courses being too “packed” with activities, methods, unnecessary assignments, and anxious attempts by instructors to cover content. While those happen in traditional classroom courses, the liabilities are exacerbated in the online environment. The One Question to Ask Instructors and course designers can achieve greater effectiveness and elegance in their courses by asking one question before using a method or student learning activity. That question is: “What pedagogical function does this method or activity serve?” By that we mean, Will the activity help students achieve the learning outcome? Is the method worth the effort related to student learning outcomes? Is the method or learning activity directly aligned with a course learning outcome/objective? Pedagogical Functions The pedagogical functions of methods and student learning activities fall into four categories. If a method or activity does not clearly serve these functions, don’t use them. The four functional categories are: (1) orientation, (2) transition, (3) evaluation, and (4) application. Orientation. Orientation methods or learning activities are used to create motivation for learning. Creating “interest” is insufficient for meaningful learning. Motivation goes to meeting an unrealized need. An orientation activity may involve helping students become aware of or identifying why they need to learn what your course offers. Orientation methods can also provide a structure for interpreting or visualizing the course content. Finally, orientation methods help introduce the course or lesson learning outcomes. Transition. Methods that provide the function of transition are those that help students go from the known or previously covered material to the new, novel, or next content to be covered. They provide a bridge to help make connections for more efficient learning. These are methods or learning activities with which the student is familiar and often use examples and analogies. Evaluation. Evaluation methods or learning activities are used to help students, and you, the instructor, evaluate previously learned content before moving on to new material, or, prior to an application activity. These activities are more effective when they are student-centered or student-developed. They help students give evidence of understanding and help instructors uncover misunderstandings. One rule to remember: if you are not going to evaluate it, don’t teach it. Application. This one is self-evident. Application methods or student activities are those that provide students opportunity to actually apply what they have learned. Student attainment of learning should be “demonstrable.” Therefore, choose application methods that facilitate ways students can demonstrate their learning. Students demonstrate application by using what they have learned in new or novel ways and/or in real-world situations (and sometimes in simulated situations). Application methods should be directly aligned with the published course learning outcomes. Can you identify how your teaching/learning methods or student learning activities serve one of the four pedagogical functions? Here’s a challenge: to avoid overwhelming your students in your online course choose one method or learning activity for each of the four pedagogical functions. That can be sufficient to achieve your course’s learning intent without overwhelming your students.

When I occupy the authoritative epistemological space, when I take my place, at the head of a biblical studies course as a black woman, I am conscious of the radicalness of my embodied performance, intellectually and physically. White men are considered by the majority of academics to be the quintessential biblical studies experts, which is not unrelated to racism and sexism and their impact on white and nonwhite scholars and students. My intersectional identity as a black woman New Testament scholar and my decentering work are both disruptive of white men’s positionality and epistemological superiority. Sherene Razack states that “a radical or critical pedagogy is one that resists the reproduction of the status quo by uncovering relations of domination and opening up spaces for voices suppressed in traditional education.”[1] This blog post is my third critical reflection on the pedagogical collaboration between Dr. Dan Ulrich and me in which I taught a summer course on African American Biblical Interpretation and the Gospel of Luke for Bethany Theological Seminary/Earlham School of Religion and Columbia Theological Seminary students. I was the teaching professor, and Dr. Ulrich was the learning professor. He is a white cisgender man who has taught for over twenty-nine years; I am an African American woman with over fourteen years’ experience teaching biblical studies (for most of my career I was required to teach both testaments, including Hebrew and Greek languages). Our syllabus identified me as the teaching professor. Because of the tendency of students to genuflect to white male authority at the expense of women and black and brown scholars, I chose not to allow Dr. Ulrich to act as an editing teacher editing teaching or to participate in the discussion forums, except the one reserved for introductions. In that forum at least one white student stated that she looked forward to learning from Dr. Ulrich. I sensed there were times when some students wished Dr. Ulrich would rescue them from my authoritative and often overtly culturally-situated epistemologies and gaze. My gaze as a black woman was temporary, but the white gaze is inescapable. The white gaze to which black and brown scholars are subjected is pervasive, invading the classroom and transcending it. The white gaze requires that black and brown peoples constantly fortify themselves against attempts to diminish and discount their epistemological resources and constructions, especially when (or to preclude or mitigate) the decentering whiteness. I sometimes invited Dr. Ulrich to contribute to the discussion, but I never relinquished my authority. To be under the white gaze is to be constantly on guard. I did not attempt to prove the legitimacy of my presence and authority but to stand in it, unapologetically, in each synchronous class session and discussion forum. I did hesitantly, at first, include Dr. Ulrich in the Zoom small group break-out sessions. Each time, I visited every group except the one to which I randomly assigned him. I had to trust that he would respect my authority even when beyond my gaze, and I believe he did. I did not police him in those groups. I do not know if Dr. Ulrich experienced to any degree, even if for a few hours for two weeks, the gaze or surveillance to which black and brown bodies are subjected perennially. White professors often include our works as required readings, but the extent and the ways in which students are permitted to value or accept them as authoritative or legitimate are policed. For example, black students have complained of white instructors teaching feminist courses that include womanist readings but that also subsume womanism under feminism, as if it is feminism’s intellectual child, or mitigate womanism’s political agenda by alleging that womanism is not as political, if at all, as feminism. During this COVID-19 pandemic, more white scholars are inviting black and brown scholars into their classrooms via Zoom to discuss their works. Hopefully, these opportunities for hearing from the scholars themselves will limit attempts to diminish and/or misrepresent our work, whether intentional or not. When I occupy the space at the head of a classroom, even when a white male colleague does not occupy the seat of learner, I do so in the minds of many students, across race, ethnicity, and gender, as a proxy or surrogate for white male biblical scholars/ship. Over the years, (last year was no exception), students, primarily white across gender, have made statements like “Dr. [white male] does it this way or said this.” Early in my career, two separate white women students, in two separate courses—one in biblical hermeneutics and one in Hebrew Bible—believed it their duty to notify me that “they did not have to agree with me.” One objected to my use of the NRSV with apocrypha, informing me that it was not a Christian Bible. I don’t remember to what the other woman objected. But in my mind, their objections had more to do with who I am—a black woman—than with what I asserted. I was the first black woman biblical scholar hired at that institution. In most seminaries and theological or divinity scholars, students will never be taught by a black man or woman biblical scholar. Unsurprisingly, of twenty-one students who responded to one of the collaborative course the course Moodle polls, only one had ever taken a Bible course taught by a black biblical scholar. One student had read a book by a black woman biblical scholar (that same student). All except one student had never read anything more recent than True to Our Native Land (2007). Black biblical scholars have published quite a bit since then. My work in that volume is a lot less progressive than my current work. In fact, as I noted in a previous blog, Dr. Ulrich stated that had he read my more recent work, he might not have asked me to teach this course. I am clear that my work is “radical” in relation to malestream Eurocentric biblical interpretation. It is still radical to encounter a black woman at the center or helm of a biblical studies course; it remains radical to center the bodies, voices, struggles, creativity, oppressions, scholarship, and communities of black women and men. In another Moodle poll, students responded to the question about reading black biblical scholars. For them black biblical scholars, black theologians, and black ethicists are interchangeable; they listed James Cone, Delores Williams, and other nonbiblical scholars, for example, in response to the question about the black biblical scholars they had read prior to this course. This response highlights the uncritical commodification and racialized substitutability of the intellectual contributions of black and brown peoples, that is less often encouraged and does not so readily occur with white biblical scholars. Instead of taking the time to find works produced by black and brown biblical scholars, white scholars and students, especially, will substitute one black or brown body for another in their publications and in biblical studies classrooms. An anti-racism agenda requires that we do differently. Notes [1] Sherene H. Razack, Looking White People in the Eye. Gender, Race, and Culture in Courtrooms and Classrooms (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 44. This process of revelation and disruption is accomplished through “the methodology of storytelling.”

Character formation plays a crucial role in enabling students to engage effectively in endeavors related to social justice and civic engagement. I have wrestled for a long time with how best to help students respond to societal challenges such as inequity, prejudice, and discrimination that they face or observe. As an ordained clergy of the Wesleyan Church, I fully embrace my denomination’s rich tradition of social justice. In addition, I seek to live out the belief that humanity can experience deep spiritual transformation that leads one to embody Christlikeness. I integrated these concepts in my teaching very early on in my career. However, I became even more acutely aware of the centrality of character formation to my teaching when I joined the faculty at Indiana Wesleyan University. The University’s mission statement reads, “Indiana Wesleyan University is a Christ-centered academic community committed to changing the world by developing students in character, scholarship, and leadership.” Every semester, I would teach one or two sections of the BIL102—New Testament Survey course as part of the General Education core. One of the purposes of the GenEd core is to help students begin to embrace Indiana Wesleyan’s World Changing mission. In the course in question, I design the learning in alignment with the purpose “to develop and articulate a Christian way of life and learning that enables virtue, servant leadership, and citizenship in God’s Kingdom.” Since every student has to take BIL102, I relish the opportunity to have students from different backgrounds engage the biblical text. During the class, I am intentional about challenging students not only to engage the text but also to encounter the person about whom the text speaks: namely Jesus. In our reading of the Gospel of Mark, I focus particularly on Jesus’s encounters with the marginalized. I use narrative techniques to help students place themselves in the shoes of different characters, and challenge them to wrestle with the implications of reading the text from different vantage points. More particularly, I ask them to name an aspect of Jesus’s identity and character that they can emulate. I remember the day a student described Jesus as “sassy.” I was shocked! I am not a native English speaker. The definition of “sassy” that I learned—rude, impertinent—did not match what I knew of Jesus, nor what I hoped my students would want to emulate. Thankfully, I managed to not voice my initial reaction, “How did you get that from the text?!”, but instead replied, “Tell me more!” The student went on to describe Jesus’s direct and, in her words, “no-nonsense” posture toward people. The student used Jesus’ interaction with the Syrophoenician woman in Mark 7 as a case in point. I conceded to the student that Jesus’s words seemed harsh, and I allowed the class to enter and dwell in the awkwardness and difficulties of the narrative. In the end, I was successful in encouraging the student to think of a different way of describing Jesus. My success was short lived. As we journeyed through the Gospel of John, the student became even more convinced of Jesus’s sassiness. I realized that it was necessary for me to pause and grasp the way the student understood the word, and what they were seeing in Jesus’s interactions with people. It dawned on me that Sassy Jesus was appealing because of the balance of truth telling and deep compassion that he displayed. While I struggled initially with the concept, Sassy Jesus eventually became part of the New Testament Survey experience. As I helped students prepare for a lifelong commitment to service and engagement as world changers, the idea of being bold and courageous in telling the truth while showing deep love and compassion began to take root. They found Sassy Jesus to be a relatable person. They found it less difficult to emulate and embody the requisite balance to speak the truth in love. To participate effectively in endeavors surrounding social justice and civic engagement, students need to be resilient and compassionate. It has become more and more difficulty to maintain this balance in public and private life. On the one hand, people hesitate to challenge or call out another person for fear of being viewed as intolerant. On the other hand, there is a tendency to confuse love and compassion with conformity and/or compromise. Jesus mastered the art of welcoming and going to people with whom he disagreed, people who were outcasts, and even people who thought they had everything figured out. He knew how to show them unconditional love and how to challenge them to embrace a better way of life, the way of the Kingdom. One of the greatest challenges we face as educators is to help re-create environments where students not only learn the skills but also develop the character necessary to engage in irenic conversation about difficult issues. We need to design learning opportunities that produce growth and maturity that lead to boldness. We need to construct experiential learning opportunities that build empathy in our students. This will enable them to stand against injustice, prejudice, and discrimination. It will empower them challenge others with the boldness and compassion that come from emulating and embodying the character of Sassy Jesus.

I met Rev. Jesse Jackson at an Interfaith Conference in Doha, Qatar. It was the first time I heard him speak in person, and during his plenary talk he covered the importance of interfaith dialogue. As I listened to how we human beings, in all our diversity, triumph, and affliction, are measured with one yardstick, I remembered the first sentiment Rev. Jackson stated that resonated with me: We often look at the strangers standing next to us as transient newcomers in our lives— bearing different skin and newborn, young, and weathered faces—but that stranger next to us often stands there as a distant reminder of ourselves, a reiteration of our experiences, a reflection we must welcome and embrace as our own. Such a notion may have been spouted during countless sermons in my life, however growing up in a strictly conservative evangelical household, I was taught that Christianity was the only way. I believe this is one of the ultimate pitfalls in Christianity and other major world religions: the denial of other faiths and faith believers. It draws every person of faith to believe that all other religions must be evil, and thus their followers must also be evil. It took decades of spiritual journeying and education to overcome this false belief, and led to a point in my career where interfaith dialogue became a preeminent focus. While perhaps I was led to this cause for personal edification, I began teaching the “Interfaith Dialogue” course with the intrinsic perspective of social justice as the human pillar upon which my students could act. In this way, interfaith dialogue is not relegated to classrooms and conferences, but belongs in our streets, our churches, and our homes. After meeting Rev. Jackson all those years ago, I have had opportunities to work with him on numerous issues. What comes to mind first, as it is so close to home, is our work on the South Korea, North Korea peace process, where we fought to free Kenneth Bae from North Korean prison. Overall, the issues we have collaborated on are founded in racial and gender justice, and culminated in my editing his book, Keeping Hope Alive (Orbis Books), a selection of his sermons and speeches as one of the foremost figures of civil rights in American history. While working with Rev. Jackson, I became aware of our unequivocal ties, not just to our personal history as teachers and theologians, but also to our ancestry. Truth be told, one cannot help but be reminded of one’s past in this country as an African American, especially during this tremendous time of uprisal, protests, and activism following George Floyd’s death, all insulated within the disorder of the world pandemic. It is as if every story of another black man’s death, a new case of police brutality, is yet another immersion of an iceberg’s tip. We are surrounded by such iceberg tips -- the question is whether we as a wider culture will be pushed to surface these and reveal the singular iceberg of racial injustice and create lasting, dynamic change. During this time in which I oscillated between the news, Twitter, work, and occasionally chatting with Rev. Jackson, I was constantly reminded of just how much I didn’t know; how many stories are untold, and how just as many stories are misunderstood through a majority lens. It challenged me to confront my own history and ancestry as an Asian American woman, and the strange places of marginalization and liminality that I find myself in. Such contradictions and challenges with racial identity come into relevance when examining interfaith dialogue and how we can contextualize from a stringent dogma taught in progressive faith movements to a more universal and enduring truth. What I learned alongside Rev. Jackson has deeply informed my curriculum and pedagogy. One thing I learned is that fighting any form of injustice requires collaboration with those who are similar to us and also those who are different from us. We need to work with Christians and with those of other faith traditions. I experienced this firsthand during my first meeting with Rev. Jackson in Doha, as we held offsite interfaith communications with Muslims, Jews, and Christians. Since then, I have been with him as he met with Muslim and Jewish leaders in the United States to work on eliminating islamophobia and anti-Semitism. Without dialogue, there is no diversity in thought, and thus the possibility of change moves farther and farther away from us. Without dialogue there is no confrontation, and thus, no peace. This is why I adamantly require dialogue, debate, and challenge from my students. As teachers, we must exemplify what we teach. Social justice is threaded through my teaching. When I talk about racial justice and easing the tension between groups of people of different ethnicities and religions, my exemplary work with Rev. Jackson finds its way into the classroom. There have historically been tensions between African Americans and Asian Americans, as experienced during the LA riots and Baltimore riots. The visual and symbolic representation of Asian Americans working hand-in-hand with African Americans is important in the classroom as well as outside the classroom. An Asian American woman working with Rev. Jackson exemplifies a wider ripple in collaboration across all communities, all fields, and offers students a realistic depiction of what they can anticipate and practice in their professional lives. Social justice work is ongoing and it is important to recognize the intersectionality of interfaith and racial justice, as Rev. Jackson encourages. To fight for racial justice also requires us to fight against gender injustice, sexual injustice, climate injustice, etc. Recognizing the intersectionality[1] of these issues provides students with the agency to create some kind of real-world impact; whether you are teaching Interfaith Dialogue, Liberation Theology, or homiletics, social justice issues unify with our work and therefore should be recognized in our pedagogy. To help my Interfaith Dialogue students engage deeper, I take them on a day trip to Indianapolis to visit a Hindu temple, a synagogue, and the Interchurch Center. At these three sites, we engage in dialogue with the Hindu leader at the temple, a rabbi at the synagogue, and the executive director at the Interchurch Center. These engagements and encounters are fruitful, enlightening, and pedagogically important. Some students have said that that the dialogue trip was the first time that they ever met a person of Jewish faith, or a Hindu, and that it was a profoundly enriching way, perhaps the most honest way, to engage in dialogue with them. Many students mentioned afterwards that this physical visit and dialogue was one of the most important events in their learning process. When people meet and engage in critical dialogue, it deepens their sense of social engagement and feeling for social justice from a mere lofty aspiration to a personal, grounded intention. This is what I experienced while working with Rev. Jackson. This was the type of dialogue we engaged in when I first encountered him and worked with him in Doha, and which I continue to practice on personal level, and ultimately share with my students. I have learned tremendously from working with Rev. Jackson and hope that our continued work and collaboration with make a pathway for others to collaborate and work for justice. Author’s note: Grace Ji-Sun Kim is presently working on a new book, Rev. Jackson’s Theological Biography. [1] For more information on intersectionality, please read Intersectional Theology, Grace Ji-Sun Kim & Susan Shaw, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2018).

Categories

Write for us

We invite friends and colleagues of the Wabash Center from across North America to contribute periodic blog posts for one of our several blog series.

Contact:

Donald Quist

quistd@wabash.edu

Educational Design Manager, Wabash Center

Most Popular

Why I Talk to My Students Every Semester About Gender Bias in Teaching Evaluations

Posted by Gabrielle Thomas on January 13, 2026

On Plagiarism and Feeling Betrayed

Posted by Katherine Turpin on October 27, 2025

The Top Five (2025)

Posted by Donald Quist on December 15, 2025

Executive Leadership Involves New Questions

Posted by Nancy Lynne Westfield, Ph.D. on December 1, 2025

Adopting a Growth Mindset in Times of Uncertainty

Posted by Emily O. Gravett on May 22, 2020