Resources by Ralph Basui Watkins

My first year at Fuller Theological Seminary, teaching Introduction to Black Theology, I failed myself and my students. I opened the class with a twenty-one minute clip of the most brutal scene from the television mini-series Roots, which aired in January of 1977. The clip showed Kunta Kinte, brutally beaten with a whip, being hung from a post while other Africans were made to watch. He was beaten near to death and made to renounce his African name and refer to himself as Toby. With every lash of the whip the students squirmed in their seats. The lights were out in the room, I knew something was happening but I couldn’t see, literally and figuratively. When I cut the lights on after the clip had played, the students were crying. One student got up and ran out of the room, wailing. The clip had traumatized my students. The students were not prepared for the clip. I had not expected this response. I had not prepared them. They were a mess. The classroom was in disarray and I was paralyzed. I was not prepared to handle this level of emotion. I stood in front of the class stunned, and feeling like an incompetent professor. How did I allow this to happen? Why didn’t I know better and do better? What now? What do I do? I don’t know. I stood helpless, in silence as the students wept, wiped their eyes, sniffled and sat. Sat, still yet squirming, and I couldn’t move. I looked at them, with no direction or leadership to offer. No words of comfort. No instruction. We sat together. As we set listening to the sounds of our emotions, there was an eerie feeling that came over the room. A feeling I couldn’t name. It was in the silence that we found our way. We wept together in this moment. This moment, pregnant with failure, birthed a new beginning. Not the beginning for the class I had anticipated, but something else. We sat in that moment, talked about our feelings. We felt in that moment and it opened a door. A door I didn’t see and could not predict. The door was a new opening to what teaching could be. Teaching could be emotional. The door of the classroom as a space of embodied experiences. Students and professors gather in the sacred space of the classroom not to be taught, but to experience the presence of the Spirit. The classroom is not just a place we experience in our minds. It is a space to be embodied, to be felt in our hearts, our emotions, our cries, our tears our love. Our love for those whose stories we revisit that shape our own. This is my story; a story I pray I never forget. What is your story of failure? A failure that led to a breakthrough.

On March 1st, the Wabash Center released a new volume of its Journal on Teaching centered on the theme of "Changing Scholarship." The issue features a multi-media essay called, "The Mother of Teaching, Ms. Earlene Watkins: A Real Mother for Ya," by Dr. Ralph Basui Watkins. The piece explores how Watkins' mother modeled for him a transformative, holistic approach to teaching. Accompanying the essay is a playlist on Spotify: Click Here to Listen. Below, Watkins walks us through his song choices and how he cultivated the soundtrack for his recent contribution to JoT.

We get that email from the library staff asking for our book selections for our upcoming course. We have taught the course before, so the library is kind enough to send the list of books we used the last time. In most cases we use the same books, but from time to time we add a new selection. Our courses look the same, they sound the same, and in many instances we teach the same books that we were taught. We can become complicit in petrifying the canon. Even if it is a new canon, it becomes constrictive and many of our courses privilege reading. We start with “books.” What if we started with the visual, sound, and look of the course? What if we were bold enough to do something we had never dreamed of doing in a course, designing experiences that were inherently transformative? I propose that if we are to do the new, the challenging, the daring, the unusual, we have to expose ourselves to the new in our daily life and practice: my wife and I dared to kayak! We had never kayaked before but as our practice is to do the new in the schools that we serve, we are doing new things that will make us new. Things that will expand us and transform us. We took an REI Class on kayaking at Sweet Water Creek State Park in Atlanta. The park is only thirty minutes from our home but when we’re on that lake it feels like we’re miles away. In doing the new, we are becoming new. Becoming new naturally pushes me to try the new, to experiment and develop classes that take students out to kayak with me. While we might not literally kayak, we will do the new, the different, the exciting. The more we do the new, the more we will try the new. Try something new and exciting that takes you out of your comfort zone and see how these experiences transform your teaching!

I can’t afford a boat but I can rent one. I spent a day on the water with my wife, Dr. Vanessa Watkins, her sister Dr. Adriana Higgins, and my brother-in-law, Rev. Michael Higgins. This time with family and friends doing something out of the ordinary, inspires my creativity. I had never been out on a pontoon boat before and never driven a boat; but, here we were having fun, laughing, talking and enjoying each other. It was one of the most relaxing times of my life. I cannot quantify how this might have affected my creative energies, but I know it did. A big part of being creative is enjoying life, having fun and relaxing. When we are able to relax, we allow our brains to rest and be restored to create. I encourage you as a teacher, professor and creative to make time to do new things with family and friends. It will bring joy to your life and invigorate your creativity. Caption: My family and me on a pontoon boat in Red Mountain State Park, Ackworth, GA. ©Ralph Basui Watkins

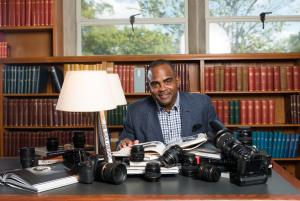

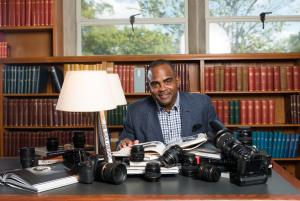

When I got my PhD in 1997 and began my teaching career we were just being introduced to PowerPoint. I like many others remember those days which have long since gone. Over my career we have moved from the use of PowerPoint to teaching in classrooms where students have laptops, tablets and phones. Students are engaging life through the screen. What does it mean to teach in an age where our students are being shaped by what they have in their hands? How do we focus our teaching in light of our student’s reality of living in an age where they are learning via moving and still images? How does our teaching align with how they see the world via Instagram, YouTube, TikTok and Facebook? We live in a world where, “…three hundred hours of YouTube video are uploaded every minute. Six billion hours of video are watched every month on the site, one hour for every person on earth. The 18–34 age group watches more YouTube than cable television. (And remember that YouTube was only created in 2005.)[1] “Every two minutes, Americans alone take more photographs than were made in the entire nineteenth century.”[2] We have become a world of image makers and these images have become our primary way to engage the world, learn about the world and our students are visual learners and much of our teaching is literate and oral. I propose that we embrace the visual world and learn as our students learn so that we can become more effective pedagogues. In his book How to See the World, Nicholas Mirzoeff articulates aspects of the contemporary visual age and provides insights about the history of visual media since 1930: As early as 1930, an estimated 1 billion photographs were being taken every year worldwide. Fifty years later, it was about 25 billion a year, still taken on film. By 2012, we were taking 380 billion photographs a year, nearly all digital. One trillion photographs were taken in 2014. There were some 3.5 trillion photographs in existence in 2011, so the global photography archive increased by some 25 percent or so in 2014. In that same year, 2011, there were 1 trillion visits to YouTube. Like it or not, the emerging global society is visual. All these photographs and videos are our way of trying to see the world. We feel compelled to make images of it and share them with others as a key part of our effort to understand the changing world around us and our place within it.[3] So, what does this mean for me and what does it mean for us? For me it has meant a complete shift in how I teach. I have moved from thinking first about lecture, words, reading and content to thinking visually. How will I engage the eyes of my students so that I can touch the mind of my students? How can I help them see what we are thinking about in this course as it lives in the world as an image that expands their imagination? Imagining the image expands the imagination of students who live in a world of images. The image becomes the lens by which my students enter this world on a daily basis therefore I start with them in my viewfinder. I see them as they see the world and because this is their starting point it is my starting point. I am teaching with them in sight, I see them looking at their phones, I see what they see and as they see so that I can teach in the visual language that they understand. My students sleep with their phones beside their beds and before they brush their teeth in the morning, they pick up their phones and start their day looking at images. I want my courses and my content to be on their home-screens. This is the world in which we live, this is the age in which we are called to teach. I had to change how I see my teaching so that my students could see what I am trying to get them to engage. This has been a major shift for me. It called me to go back go to school to learn how to see so that I could become an effective teacher in the visual age. I talk about my shift and embrace of the world in which we live in the short video that accompanies this Blog. In this video we are celebrating my installation in an endowed chair. The video speaks to the shift I have made, and I invite you to consider. What does it look like to teach in the visual age (pun intended)? Teaching in the Visual Age: Dr. Ralph Basui Watkins from Ralph Watkins on Vimeo. [1] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. How to See the World (4). Basic Books. Kindle Edition. [2] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. How to See the World (4). Basic Books. Kindle Edition. [3] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. How to See the World (4-5). Basic Books. Kindle Edition. *Original Blog published on December 11, 2019

As a writer and a teacher I am always looking for ways to inspire my creativity. This summer I have committed to a practice of getting out in nature. I will be visiting national parks, state parks and doing some cabin stays. The goal is to incorporate the sounds and sights of nature as I seek times of solitude, stillness and quiet as keys to my inspiration. The first such trip this summer was to The Getaway two hours north of Atlanta, with a stop by Chattahoochee– Oconee National Forest. The video below shares my experience. My hope and prayer is that you might be inspired to find the practice of being in nature, solitude, stillness and silence as a means to fuel your creativity as a teaching professor. Photo 1: CHATTAHOOCHEE–OCONEE NATIONAL FOREST @RALPH BASUI WATKINS Photo 2: THE GETAWAY @RALPH BASUI WATKINS [su_spacer size="20" class=""] [embedyt]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CuhjCWFrAic[/embedyt] [su_spacer size="20" class=""]

We walk into our classrooms, be they virtual or face-to-face, and we see the eyes of our students with screens in front of them. Those screens may be laptops, desktops, tablets, or phones but the screens are there. On those screens our students spend an average of four hours per day, engaging moving and still images. We then ask them to read and process something that was written by someone they will never see or hear. We expect them to be fully engaged by the reading. The social justice issues they are reading about are hidden beneath text on a page. While reading is essential, it is limiting, and it especially limits the mental capacity of the students we teach today whose minds are wired to engage moving and still images via stories. Our students need to see to fully connect with that we are studying. If we are to teach to their strengths we need to show them the subject matter. The way we show them is by using documentaries as the foundation of course design. Listen to Albert Maysles as he speaks on the power of documentaries: [embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_yABhT20Hs[/embedyt] Documentaries put students in the midst of the social justice issues we are studying. They can see, feel, and connect, not just with the issue, but also with the real people who are affected by injustices. Nick Fraser says in his book Say What Happened: A Story of Documentaries, “docs have morphed into contemporary essays, becoming a form whereby we get to experience highly provisional stabs at reality, but, far more than fictions, which are usually finished and fixed in their own reality, they are also transformed by it.”[1] Documentaries are the new essay; we have access to a new type of reading made just for the generation of students we are teaching. We need to honor them by showing them and in the showing they are seeing what was, what is, and what can be. We work in an industry that values the written and spoken word over the visual. We were taught to plan our classes starting with the reading—readings that were written years before our time mostly by dead white males. I always found these readings alien to me when I was a student, and even those I connected with were usually written by people many years my senior. There was still this disconnect because of the faded pages from which I read; I was removed from them by time and space. None of what I have said makes these works irrelevant or useless but it highlights the limitations of readings. When I think about the students I teach today who view more than they read I see that they are deep thinkers, they are intelligent, they can read and write, and they also bring a more expansive set of communicative and interpretive skills to the classroom than I did when I was a student. The question I am raising in this blog is: How do I engage what my students bring to the classroom so that I can show them what I want them to learn? Yes, show them. To answer my question, I am suggesting that we show our students the social justice issues we are discussing in class while showing them how movements work by engaging documentaries as the core content for our courses. I am not dismissing books and readings, but I am displacing their historical place of privilege. Why documentaries? Documentaries speak to the head and the heart. Documentaries help students see and feel by eliciting the emotive response in the visual. More centers of the brain are activated by sound, movement, light, story, and real life characters who lived in the movement. Students see history and how they can make history. I have also found that conversation after a documentary is democratized unlike those after reading discussions. Reading discussions privilege certain types of students whereas discussion around documentaries has a way of leveling the playing field. Students feel more equipped to talk about that which they have seen, engaged, and understood. As Cathy Chattoo says in her book Story Movements: How Documentaries Empower People and Inspire Social Change, Documentary is a vital, irreplaceable part of our storytelling culture and democratic discourse. It is distinct among mediated ways we receive and interpret signals about the world and its inhabitants. We humans, despite our insistence to the contrary, make individual and collective decisions from an emotional place of the soul—where kindness and compassion and rage and anger originate—not from a rational deliberation of facts and information. By opening a portal into the depth of human experience, documentary storytelling contributes to strengthening our cultural moral compass—our normative rulebook that shapes how we regard one another in daily exchanges, and how we prioritize the policies and laws that either expand justice or dictate oppression.[2] Documentaries connect with us because we are wired for story and true stories told well speak truth to us and set us free to be part of the freedom movement. So if we are to start with documentaries as the foundation of our courses, and use readings to complement the documentaries, where do we start? Let me offer a few questions that might get you thinking: What do I want my students to see? Why is the visual experience of this course as important as the reading(s)? What do I want my students to hear? What do I want my students to feel? Why is it important for my students to engage the sights and sounds of this experience so as to bring to life that which we are studying together? What do I want my students to do about social injustice as a result of experiencing this course? How can I create and curate a visual experience that is buttressed by quality readings that will make this course be more than memorable, but will make it serve as a launching pad for social justice initiatives and actions in the real world? How can I make the viewing experience a communal experience and make it as unlike the isolating experience of reading as possible? What documentaries are worth my students’ time, in that they are well told stories, well researched, historically accurate, factual, and emotionally stimulating? So now you might ask what could this look like? What are some documentaries one might consider? There are of course many but allow me to offer a list I have used for courses where the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s has been the foundation of the course. The list below is just one such list to get you thinking about what a curated list of documentaries would look like, and about the order which they would be engaged. A Civil Rights Course Lineup (in this order): The Murder of Emmet Till (2003) 53 minutes Directed by Stanley Nelson The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords (1999) 86 minutes Directed by Stanley Nelson Eyes on the Prize: Season #1 – 1952 to 1965 (1987) 42 minutes each Directed by Henry Hampton and others Mavis (2015) 80 minutes Directed by Jessica Edwards 4 Little Girls (1997) 102 minutes Directed by Spike Lee Mr. Civil Rights: Thurgood Marshall & The NAACP (2014) 57 minutes Directed by Mick Cauette Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015) 115 minutes Directed by Stanley Nelson Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin (2003) 90 minutes Directed by Nancy D. Kates and Bennet Singer Movin’ On Up: The Music and Message of Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions (2008) 90 minutes Directed by Phillip Galloway Freedom Riders (2010) 117 minutes Directed by Stanley Nelson John Lewis: Good Trouble (2020) 96 Minutes Directed by Dawn Porter King: A Filmed Record Montgomery to Memphis (1970) 240 minutes Directed by Sidney Lumet King in the Wilderness (2018) 111 minutes Directed by Peter W. Kuhardt The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975 (2011) 92 minutes Director Göran Olsson Wattstax (1973) 103 Minutes Directed by Mel Stuart Chisholm ’72: Unbought and Unbossed (2004) 66 minutes Directed by Shola Lynch I Am Not Your Negro (2017) 93 minutes Directed by Raoul Peck Documentary Associations and Resources: Fireflight Media http://www.firelightmedia.tv PBS Civil Rights Documentary http://www.pbs.org/black-culture/explore/10-black-history-documentaries-to-watch/ HBO Documentaries https://www.hbo.com/documentaries International Documentary Associations https://www.documentary.org Doc Society https://docsociety.org Odyssey Impact https://www.odyssey-impact.org Impact Field Guide https://impactguide.org American Documentary https://www.amdoc.org/create/filmmaker-resources/ PBS POV http://www.pbs.org/pov/ Netflix Best Documentaries https://www.netflix.com/browse/genre/6839 Notes [1]Nick Fraser, Say What Happened: A Star of Documentaries (London: Faber & Faber Press, 2019), 28. [2]Cathy Borum Chattoo, Story Movements: How Documentaries Empower People and Inspire Social Change. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020), 207.

On Wednesday, October 7, 2020 we had our first gathering with Victor Wooten and the fifteen scholars who are privileged to be a part of this cohort. Victor asked us, “Why are you here?” Many answered while I listened. I didn’t speak during the formal two hour period, I listened. I hadn’t intended not to speak. Prior to the gathering formally beginning I was my normal raucous self but when Dr. Lynne Westfield called us to order my posture changed. If would’ve answered the question Victor posed I would’ve said: “I am here because I love music. I am here because I use music in all of my classes. I am here because I thank improvisation is the key to living full and adventurous life. I love the guitar. I love the bass. I am grew up listening to Larry Graham, Bootsy Collins, James Jamerson, Jaco Pastorious and so many more. I am a true fan of Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miler, Chritian McBride and Victor Wooten. Victor Wooten is not simply a musician but to me he is a mystic, a teacher, a scholar and brilliant. Whenever Victor Wooten is in town I am there to be a part of the experience.” Everytime Victor comes to Atlanta I am there (the links below are to photo galleries of two of my recent experiences at a Victor Wooten concert). Victor Wooten at the Variety Playhouse in Atlanta, GA https://flic.kr/s/aHskZV22bG https://flic.kr/s/aHskzJKr6A I was in this cohort for the experience. I wanted to experience what it meant to be with Victor and my colleagues to do this work together, to grow together and reimagine what teaching could be for us in the present age. [embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GONEnFyj73w[/embedyt]

We can teach the ongoing struggle for civil rights by taking students to the current day struggle via Instagram and sacred sites. Who on Instagram is doing the work that the great ancestral photographers like Mikki Ferrill, Louise Martin, Moneta Sleet Jr., John Shearer and Gordon Parks did? One is Joshua Rashaad McFadden. His Instagram is liberative in every way. We can invite our student to share who they are following, while also inviting them to follow those doing the work of showing us the struggle. What this does is show the students the power of photography in the liberation struggle yet lives as it did in the 1950s and 1960s. Moreover it takes them out of the classroom and into the real world via a virtual photography feed. The second step in this process is taking student to sacred sites that are living. When you go to the field and experience the sites where the struggle occurred in your town or the town the student is living in, if they are taking the course online. Go and see, feel and hear the power of the sacred sites where the struggle was and is being waged. In the video below I take you to the sacred site where we in Atlanta honored the life of Rayshard Brooks. Rayshard Brooks was lynched by the Atlanta Police Department on June 12, 2020. The Wendy’s where the lynching occurred has become a sacred site of remembrance and resistance. I take you there in this video and you hear from one the leading modern day civil rights photographers alive today. Joshua Rashaad McFadden is someone you want to follow. May the videos speak for itself. http://www.joshuarashaad.com https://www.instagram.com/joshua_rashaad/ [su_youtube_advanced url="https://youtu.be/XpFNU0eKzwA"]

[su_youtube_advanced url="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1v1Z7Yj0OU&feature=youtu.be"] Teaching is an inherently creative act. We have been taught to teach as we were taught. I was taught by classic lecturers. If it wasn't the lecture it was the socratic method, seminar method or students present and lets see who can do the best. When I started teaching I taught like I was taught. I have come to discard the old ways of teaching and allow myself and my students the freedom to explore and create an experience that is saturated with the creative spirit of the times in which we live. In this Vlog I ask what creative rhythms do you have in your life that inspire creativity in your teaching? I share my creative rhythms and I invite you to celebrate yours and realize how they inform the creativity in your teaching.

When we engage our teaching world online, let me encourage you to start where you are. It is not about the tech, gear and gadgets. It is about vision, imagination and design. In this vlog I show you my setup, my online classroom and how I think about this space. This is not a “how to video” but rather it is a glimpse into my inner world. I want to invite you to dream about your space, your vision for online teaching and how this might look for you. My goal is to inspire you to think deliberately about your presence and vision for your online classroom. [su_vimeo url="https://vimeo.com/403354389" title="My Online Classroom"]

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="562"] Egypt https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/43570551171/in/album-72157669384150857/[/caption] What is the promise of documentaries for teaching and changing the world? Is the documentary the new pedagogical model for everyday classrooms? Is the professor of tomorrow not a lecturer or one who uses the Socratic method, forums, discussion boards, and blogs, but rather are they documentarians? Is the professor of the “now “ one who makes their own documentaries as content for their classes? Is this the game changer? Nick Fraser, in his book Say What Happened: A Story of Documentaries says, “. . . docs have morphed into contemporary essays, becoming a form whereby we get to experience highly provisional stabs at reality, but, far more than fictions, which are usually finished and fixed in their own reality, they are transformed by it. . . . . The best docs celebrate a sense of the accidental. And they matter. Like unknowable bits of the universe, they come into existence when a collision occurs.”[1] Fraser argues in his book that documentaries matter, they change the way we see and engage the world. Documentaries educate us, transform us, and challenge us. Fraser argues that the documentary is the new long form essay, it is what people are watching as they read. We are no longer a culture that is rooted solely in the literate and oral tradition, but a new tradition has emerged and it is the documentary as reliable scholarly source. If Fraser is right, and I believe he is, then how does this new reality expand our opportunities to teach in ways that are truly transformative and liberating? In my Evangelism and Social Justice course I assigned Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness along with Ava DuVernay’s, Oscar nominated documentary, 13th: From Slavery to Criminal with One Amendment and to my surprise this pairing was a game changers.[2] The students got it because they read, they saw, they felt it, and our conversation was transformative. The students were able to weave the two forms of scholarship together. In this class, we were wrestling with the fact that God calls God’s church to spread the gospel and that gospel is one of justice. God is on the side of the oppressed and God calls us to set the captives free. God calls us to see injustice, call it out and address it by correcting it. We spread the gospel by being the gospel. My students got it. One of my students said to me, “I finally get what Black theology is all about. I get it and I have to do something. Thank you so much for assigning the documentary. I see it now.” When she said, “I see it now!” this was eye opening for me (pun intended). It was the wedding of these two, the written word and the visual demonstration of that word, that help my students see. My students are used to watching Netflix, all of my students had a subscription or access to someone’s subscription and this viewing came natural to them. They live in the visual world and I have found that documentaries, like books, are a part of their scholarly diet. Why not feed this appetite? Do documentaries really make a difference? Can they change the way we see the world and then make us act on behalf of justice? Let me cite one case as example of just how powerful documentaries can be. The Fall 2019 edition of The ARTnews reported, “Agnes Gund believes in giving her art away, with donations of hundreds of works from her collection to the Museum of Modern Art spanning decades and others to the many institutions she has supported. But the 81-year-old philanthropist thought she could achieve more by selling a treasured painting after seeing 13th (Ava DuVernay’s,13th: From Slavery to Criminal with One Amendment). Feeling a call to action, Gund choose to sell her favorite holding . . . for $165 million to billionaire investor Steve Cohen, after refusing his overtures for years. She then used $100 million of the proceeds from the sale in 2017 to launch the Art for Justice Fund, a partnership with the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors currently working against the scourge of mass incarceration through concrete and poetic means.”[3] Agnes Gund’s worldview was changed by engaging the work of Ava DuVernay. Gund saw and she acted! Can we get our students to see and act? Can we employ the use of documentaries in our classes in similar ways we have employed readings in the pass? Can we make our own documentaries and have them replace our lectures? What does it take to make your own documentary? All it takes is a camera, editing software, and our no-permissions-asking selves to just go and do it. In my African Roots of Black Theology class, I created a two-part documentary to start the class. The students engage my asking the question in the context that gave rise to the question. It is a new and more visceral way for them to engage in a new form of contextual visual education. My students got to travel with me as I traveled through Egypt. I used the daily vlog as way to tell the story, share my questions, pondering and musings. The students go with me to where my story begins and it begins in Africa. I also created photo albums for all major stops along my journey so that students could pause and admire the still images in conversation with the moving images. I offer these examples as a testimony of my first attempts and I look forward to seeing yours as we ask what are the now / next in pedagogical practices? Sample Documentaries: Vlog Style [su_vimeo url="https://vimeo.com/355109032" title="Part #1: Out of Egypt"] Part #1: Out of Egypt I’ve Called My Son: A Son’s Journey Black to Africa (https://vimeo.com/355109032) [su_vimeo url="https://vimeo.com/355118012" title="Part #2: Out of Egypt Final Cut"] Part #2: Out of Egypt Final Cut ) Portraits of Egypt https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157669384150857 Giza Pyramids https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157693534362690 Sakkara, Step, Red & Bent Pyramid https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157697707740291 The Cairo Museum https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157696165977282 The Temple of Aset https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157698917086034 Edfu and Komombo https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157699345621995 Luxor https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157669383738737 Karnak https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157698915679014 East Bank Temples https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157671458282618 Denderah https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157696165292492 Abu Simbel https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157697695476081 References [1] Fraser, Nick. Say What Happened: A Story of Documentaries. Faber & Faber; London, 2019. p. 28. [2] Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press; NY, 2012. DuVernay, Ava. 13th: From Slavery to Criminal with One Amendment. Netflix; 2016. [3]Sheets, Hilarie M.. “Justice League: How Agnes Gund’s $165 Million sale of a beloved painting helped get others to join the fight against mass incarceration.” In The ARTnews Fall 2019 VOL. 118, NO. 3, p. 75-76.

In 2015 my wife, Dr. Vanessa Watkins, took a trip with National Geographic to Cuba led by one of their photographers. One of the things I love about National Geographic trips is that the tour leader lectures in the hotel prior to going out to engage the culture. This leader lectured, but what blew my mind was that he never put a word on the screen. Throughout our fourteen-day trip, he always lectured with a computer, projector, screen, and images. Still images were his language of choice. He showed us what he was talking about and it was powerful. The images he shared were his images, he was a professional photographer, but that wasn’t what made the images work, it was his pedagogical decision to use the screen to project pictures. He would talk around the image; the image became the center piece of his comments and it worked amazingly well. Those images are still with me, five years later. What does this say to us as pedagogues? [caption id="" align="alignnone" width="2560"] Vanessa and Ralph Watkins in Cuba 2015[/caption] We have the big screen in our classrooms, in Moodle and Canvas, but how are we using this real estate? Are we using the screen to project words, words that we are re-reading to our students? Are we using the templates designed by engineers in Power Point who have no artistic or pedagogical training? Are we using the screen to show our students what we are talking about so that they can see it? I would suggest that we think about how we might use the screen as a pedagogical tool to show the students what we are talking about, to engage the creative centers of their brains, and to embrace the old saying, “a picture is worth a thousand words.” I would rephrase that old saying, “a picture saves us from saying a thousand words.”To use photographs in the powerful way they can be used, we have to understand why a photograph works. Better yet we have to learn to read photographs. Lets go to Cuba: This is my favorite image from Cuba. Why? This image is rich and full of information. When you read an image, you first read it from left to right. From left to right we see the juxtaposition of the old cars, a new car that is a taxi, a school bus with the backdrop of the capital. Smack dab in the middle of the image behind the newer black car is a street sweeper’s trash can. The image offers clarity, negative space (open space), and the beauty of Cuba’s sky. From the far-left bottom of the frame you see a blue car and that is put in conversation with the far-right of the frame where you see a white car. Sandwiched between these two cars is the complexity of Cuba. The capital stands as a monument under reconstruction; a symbol of Cuba’s determination to live, build, rebuild, reconstruct, and embrace its rich heritage of rugged survival. You also read an image from front to back. In the foreground we have this old blue car. The car’s headlights shine in the morning rising sun. You can vaguely make out the people in the car. The blue car greets you and it says, “Good morning Cuba!” As you move one layer back to the middle ground of the image, you see the black car, the street sweeper’s garbage can, the woman walking on the side of the school bus, the school bus, the capital, and the beautiful morning sky. The streets are clean and the streets speak of the beautiful blackness that is Cuba. This is an image that could be the opening for a lecture about my trip to Cuba. Why put words on the screen when I can put this picture on the screen? This picture takes you to Cuba. No words needed. This is an image you can talk around as you share with your students the complexity that is Cuba. When it comes to using images in our classes we need to use powerful images that tell stories and read well from left to right and from front to back. You are looking for images that speak to what you want to say, and say it in a way that brings to life the argument you are making. You have to ask what does this image say? What’s in the edges of the frame? Where does the eye go and where does it wander? What thousand words does this image say that I don’t need to say? Images speak if we look at them and listen. What are your images saying in your lectures? Here are some more pictures from my Cuba trip. I present them for your consideration to practice reading images. Start from left to right, then read the image from front to back, look at the edges of the frame and then ask, where does the eye go and what does this image say? [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] Picture #1: The City View of Havana[/caption] [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] Picture #2: The Fruit of Cuba[/caption] [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] Picture #3: Walking and Talking[/caption] [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] Picture #4: Time for Dinner[/caption] To view all my photos from Cuba: https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphwatkins47/albums/72157652605129753

I learned something this holiday season—my first holiday season as a grandfather. My family traveled from Atlanta, Georgia to Orlando, Florida to surprise my mother, Mrs. Earlene Watkins, on her 80th birthday. The surprise is summed up in this moment. [caption id="attachment_239279" align="aligncenter" width="397"] Mrs. Earlene Watkins, My Mother[/caption] My mother didn’t know that that I was coming with my wife. But, we weren’t the big surprise. The big surprise was the new addition to our family. Her new, four-month old, great-grandson, Princeton Josiah Smith. My daughter, Nicole Smith, and her husband, Walter Smith, conspired with us to make this day possible! My daughter Nastasia Watkins and I both videotaped this historic moment. I shot with two cameras: I walked in using my Canon G7 Mark II, and then I shot with my Canon EOS C100. These two cameras are what I am most comfortable with. I had to bring them in large camera bags, set them up, and prepare to shoot. In contrast, my thirty-two-year old daughter, Nastasia Watkins, shot her video with the camera she lives with: her iPhone. She not only shot this video with her phone, but she also edited the video on her phone. She posted her video within minutes. I took my video back to the hotel, edited it on my laptop in Final Cut X, and posted my video on the next day! [caption id="attachment_239281" align="aligncenter" width="392"] My Mother, My Daughter, My Son-in-law and Princeton Josiah Smith[/caption] What did I learn? Nastasia Watkins is no teenager. My daughter is a partner in her own law firm. She and her peers are completely comfortable making memories with what is in their hands. As I watched her shoot video and take pictures over the holidays, it was clear that she was always ready to shoot. On the other hand, it was more work for me. It didn’t come naturally. I didn’t use my phone. I had to go get my camera, get ready, shoot, and then put the camera down. My daughter never put her camera down. It was no challenge for her to be engaged in the moment and shoot simultaneously. I was wowed by her ability to be fully present and to capture the moment. She taught me how her peers and those coming up behind her are processing, capturing, and seeing their world. They see the world with phone in hand. Their phone is not used to make phone calls, but as a way to see, engage, make sense of, understand, and frame their world. For we teachers, these are our students. They see their world through a screen the size of their phones. If we are to understand how to engage them, we must see what they see, how they see, and how they learn to make sense of that which they engage. How do we do this? We must pick our phones up and start to use them as they use them. I have to put my big, expensive cameras down. I am recommitting myself to using my iPhone X for the reason I say I bought it: for the camera. When you see commercials about the latest phone, they never advertise the phone’s ability to make phone calls. They sell the phone as a camera. It was the commercial that sold me, and after this holiday season I have recommitted to using the most powerful pedagogical tool I have with me all the time and that is the camera on my phone. When we use the phone as a camera and editing device, we will begin to engage and make sense of the world our students live in. This will, in turn, inform our teaching and learning. We will see the phone as a teaching and learning device and not as a distraction from our traditional teaching moments. When we see the tool in our hand as a revolutionary pedagogical device, it will change how we use that which we have in our hand. [caption id="attachment_239282" align="aligncenter" width="408"] The Family at the Surprise Birthday Party for Mrs. Earlene Watkins @ 80![/caption] Well, I know you want to see the two videos . . . here you go! Video by Nastasia Watkins https://vimeo.com/382453975 Video by Ralph Watkins https://vimeo.com/382456567 Photo credit: Victor Watkins