Resources

Event Template (by Haddon) Paste into html Customize: links highlighted with red textlink to workshop pageGround TransportationAbout a week prior to your travel you will receive an email from Trish Overpeck (overpecp@wabash.edu) with airport shuttle information (pdf). This email includes the cell phone number of your driver, where to meet, and fellow participants with arrival times. Please print off these instructions and carry them with you.

Perhaps one of the most painful memories I have of my early years in teaching was election night 2004. The pain comes from my too late realization that in my advocacy for a progressive outcome for the election I had semi-wittingly politicized my classroom in a way that still haunts me. I’d like to reflect for a bit on what happened and what I learned. What happened was quite simple. I was a progressive who was against the war in Iraq and the convulsions caused to our common life by extraction of our common wealth to finance massive tax cuts. Put simply, I was ardently against Bush and made no secret of it. In the weeks leading up to the election and the evening of the it, on which I had a class meeting, my advocacy had had the effect of drawing a political line along which members of the class sorted themselves. A consequence was that for the few weeks remaining after the election my pedagogical space consisted of political partisans and not a community of learners. What I learned from that was three-fold with the full effect being felt in the recent election. The first thing I learned was that I had spent insufficient time or energy teaching about my values, what they meant for how I understood the faith, and thus, how I constructed the task of teaching theology. Here I don’t mean to imply that I understand my role as being teaching my theology. Rather I want to suggest that it is good to realize that our values are being taught whether we are explicit about it or not. Being explicit means that I can reflectively engage students and materials in ways that shape our common experience. By focusing on values I can invite more people into our space than if it is a matter of politics. I did not do this work. The second learning was that I had spent insufficient time clarifying how I integrated scripture, faith, values in the work of theology for myself. So, while I am sure that I demonstrated a sort of integrity for my students it was not sufficiently reflective to build my teaching around. Certainly, the project to which I am dedicated as a theologian was/is clear and finds expression through my teaching but, at least at that point, the integrity at the center of teaching and that project were not clear. From this learning I changed my pedagogy radically. Teaching theology and not about it became my guiding pedagogical principle. The upshot of this change was that questions of the integration of scripture, faith, and values as the work of theology were at the center of every course from its beginnings. In the two classes I taught following the recent election I began with an observation that we as Christian theologians were being called into the public square at this moment for several very specific reasons. First, the candidate who won had made very specific promises about bringing harm to the weakest and most vulnerable among us, our neighbors. By placing promises to register our Muslim neighbors, round up and deport the stranger among us (immigrants), and the imposition of what amounts to martial law (a national stop and frisk policy), at its center the Trump campaign made the political theological. It is just here that my learnings of the past few years made it possible for our class(es) to grapple with our responsibility in this moment in ways that did not immediately devolve into partisan positions. We were able to draw on scripture, the various theologians we read, and our experiences of faith to imagine how to move forward. This was quite a bit different than in 2004. This then was my third lesson. By making the ongoing thread running throughout each class the explicit integration of our faith and values, it was then possible to interpret the political moment as a matter of faith and not partisan politics. A student summed up well what we had discovered on our journey: “loving and protecting our neighbor is a type of politics.”

2017-18 Workshop for Early CareerAsian and Pacific Islander DescentFaculty This workshop will gather 14 faculty drawn from diverse religious specializations, in their first years of teaching, for a week in two successive summers and for a weekend winter retreat. As a learning community of committed and skilled teachers, this workshop will explore issues such as: Pedagogy and politics of faculty of Asian and Pacific Islander descent Being a fulfilled and engaged teacher/scholar Career growth such as tenure and alternate academic tracks Teaching and thriving in one’s institutional context Dealing with religious, social, ethnic, racial, and learning diversities in the classroom Connecting the classroom to broader social issues Course design, assignments, learning goals, and assessment There will be a balance of plenary sessions, small group discussions, workshop sessions, structured and unstructured social time, and time for relaxation, exercise, meditation, discovery, laughter, and lots of good food and drink. Goals To develop a professional network of mutually supportive teachers/scholars of Asian and Pacific Islander descent To speak candidly about the politics and pressures of teaching and learning in higher education To explore the intersections of positionality in the classroom, institution, and academy, such as race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and age To engage in formal and informal dialogue about existing and needed habits and practices of teaching in mono- or multi-cultural contexts To reflect critically on vocation, identity, and well-being that integrates the rigors of scholarship, teaching, leadership, and work/life balance To hone teaching practices and innovative pedagogies through design and implementation of collaborative projects To prepare for trends and changes in higher education Honorarium and Fellowship Participants will receive an honorarium of $3400 for full participation in the three workshop sessions, plus local expenses and travel. In addition, participants are eligible to apply for a $5000 fellowship for work on a teaching project during the following academic year (2018-19). These awards are for projects that emerge from the conversation and ideas of the workshop, in consultation with the leadership team, and are conducted during the year following the workshop. Read More about Payment of Participants Read More about the Workshop Fellowship Program Participants Front Row: Yii-Jan Lin (Yale Divinity School), *Zayn Kassam (Pomona College), *Tat-siong Benny Liew (College of the Holy Cross), *Su Yon Pak (Union Theological Seminary in NYC), *David Kamitsuka (Oberlin College), Roshan Iqbal (Agnes Scott College). Second Row: Hee-Kyu Heidi Park (Xavier University-Cincinnati), Samira Mehta (Albright College), Cuilan Liu (Emmanuel College of Victoria University in the University of Toronto), Fuad Naeem (Gustavus Adolphus College), Jung Hyun Choi (North Carolina Wesleyan College), Sailaja Krishnamurti (Saint Mary’s University-Nova Scotia), Christine Hong (Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary). Back Row: *Paul Myhre (Wabash Center), William Yoo (Columbia Theological Seminary), Harshita Kamath (University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill), Chrissy Lau (Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi), Kenneth Woo (Pittsburgh Theological Seminary), Hoon Choi (Bellarmine University). *leadership/staff position. APPLICATIONS CLOSED Workshop Information Dates First session: July 10-15, 2017, Wabash College Second session: January 25-28, 2018. Corpus Christi, Texas Third session: June 25-30, 2018, Wabash College Leadership Team Tat-siong Benny Liew,College of the Holy Cross, Director David Kamitsuka, Oberlin College Zayn Kassam,Pomona College Su Yon Pak, Union Theological Seminary in NYC Paul Myhre, Wabash Center Important Information flickr Photo Gallery for this Workshop Travel and Accommodations for Summer Sessions at the Wabash Center Policy on Participation Map of Wabash College Campus Travel Reimbursement Form (pdf) Foreign National Information Form (pdf) Payment of Honorarium Fellowship Program (2016-17) For More Information, Please Contact: Paul Myhre, Associate Director Wabash Center 301 West Wabash Ave. Crawfordsville, IN 47933 800-655-7117 myhrep@wabash.edu

2017-18Colloquy for Theological School Deans This colloquy seeks to gather a diverse group of theological school deans to engage in creative conversations about academic leadership in an age of dramatic socio-economic, environmental, demographic, and religious change in the North American context. Colloquy participants can expect to engage in collaborative learning, expand their understanding of the work of academic administration, and build a network of collegial support. Goals As peers in a collegial and confidential atmosphere, we will consider such questions as: How do you discern and affirm your vocation as a theological educator in the role of an academic dean within the mission of your institution? How do academic deans lead in times of dramatic social and religious change that directly and indirectly impact theological education? How do academic deans lead to keep faculties vital, curricula relevant, and teaching and learning the center of the theological school enterprise? Read our Policy on Participation Honorarium and Fellowship Participants will receive an honorarium of $3000 for full participation in the two sessions, plus local expenses and travel. In addition, the Wabash Center will reimburse expenses up to $500 for your attendance at the Association of Theological Schools’ CAOS meeting to be held prior to the ATS biennial in June 2018. Read More about Payment of Participants Participants Front Row: Stephen McMullin (Acadia Divinity College), *Deborah Krause (Eden Theological Seminary), *Luis Rivera (Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary), Heather Vacek (Pittsburgh Theological Seminary), Munir Shaikh (Claremont School of Theology). Back Row: Susan Abraham (Pacific School of Religion), Grant Taylor (Beeson Divinity School at Samford University), Melanie Johnson-DeBaufre (Drew Theological School), Jeanne Hoeft (Saint Paul School of Theology), Lynda Robitaille (St. Mark’s College), Valerie Rempel (Fresno Pacific University Biblical Seminary), *Paul Myhre (Wabash Center). *leadership/staff position. APPLICATIONS CLOSED Due January 17, 2017 Colloquy Information Dates First Session: July 17-22, 2017, Wabash College Second Session: April 18-22, 2018, Corpus Christi, Texas Leadership Team Deborah Krause, Eden Theological Seminary Luis Rivera, Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary Paul O.Myhre, Wabash Center Important Information flickr Photo Gallery for this Workshop Travel and Accommodations for Summer Sessions at the Wabash Center Travel and Accommodations for Winter Sessions in Texas Philosophy of Workshops Policy on Participation Map of Wabash College Campus Travel Reimbursement Form (pdf) Foreign National Information Form (pdf) Payment of Honorarium For More Information, Please Contact: Paul O.Myhre, Associate Director Wabash Center 301 West Wabash Ave. Crawfordsville, IN 47933 800-655-7117 myhrep@wabash.edu

Since the start of the twentieth century, Christian religion scholars from the dominant culture - specifically ethicists – shifted their focus on how to live the Christian life via praxis toward the nature of ethics, wrestling more with abstract questions concerned with what is the common good and/or which virtues to cultivate. An attempt is made to understand the world, but lacking the ability to differentiate within disenfranchised communities between a “blink and a wink,” à la Geertz, their final analysis lacks gravitas. Teaching religion has become a process which [de]liberates not liberates. While abstract deliberations at times might prove sympathetic to the plight of the oppressed, the first casualty of abstract thought is rigorous academic discussions concerned with how to construct a more just social structure based on faith claims. A move to the abstract has, as my dissertation chair John Raines constantly reminded me, made the [class]room an appropriate name which signifies what occurs. This “room of class” becomes a space where students learn the class to which they belong, and how to assume the responsibilities associated with that class. During a visit to Yale, a student reminded me that while most seminaries train ministers for churches, Yale trains future bishops and superintendents. I doubt if such an attitude is limited to just one of the Ivies. Those with sufficient capital or connections to attend certain “rooms of class” on prestigious campuses are afforded opportunities normally denied to others (predominately students of color) who attend rooms at less prestigious locations. To occupy [class]rooms attached to power and privilege means that what is taught focuses more on the abstract as opposed to praxis designed to subvert power and privilege. To some degree, most eurocentric approaches to pedagogy at prestigious [class]rooms, more often than not, focus on explaining what is religious. But for those rooted in (or in solidarity with) disenfranchised communities relegated to the underside of prestigious [class]rooms, the question is not so much to determine some abstract understanding of religion, but rather, in the face of dehumanizing oppressive structures, to determine how people of faith adapt their actions to serve the least among us. Some professors who embrace a more liberative approach to pedagogy recognize there is no such thing as a neutral education system. Rather, students, depending on the [class]room they attend, are either conditioned to domesticate or be domesticated. A theological education serves to normalize and legitimize existing power structures within the faith community and society. A liberative pedagogy instead seeks to cultivate the student’s ability to find their own voice by creating an environment where collective and individual consciousness can be raised. The starting point is not some truth based on church doctrine or rational deliberation. Instead, the starting point is analyzing the situation faced by the dispossessed of our world and then reflecting with them theoretically, theologically, and hermeneutically to draw pastoral conclusion for actions to be taken. To function in the [class]room as a scholar-activist is usually to be dismissed, especially if one chooses not to engage in the methodologies acceptable to eurocentric thought. A division, unfortunately, exists where those concerned with the importance of maintaining their privileged space in [class]rooms oozing with power insist on lessons revolving around the thoughts and ideas of mainly dead white scholars (and those soon to join them) dismissing scholar-activist and the scholars from marginalized communities who inform their own thoughts. Simply peruse the reading lists on syllabi at prestigious [class]rooms to notice how scholars from disenfranchised communities are ignored – except, of course for that one elective class offered to check off the political correctness box. The [class]room space is protected with a call not to engage in the politics of our society, but instead to limit our thoughts to the polity that is the church, usually a homogenous church which more often than not misses the mark. The calling to be a scholar-activist is a recognition that by seeking solidarity with the stone rejected by stale builders regurgitating dead thoughts incapable of saving anyone, one finds themselves among the cornerstone of relevant, cutting-edge scholarship capable of revolutionizing society, literally turning the world upside-down.

I help people have difficult conversations for a living. I facilitate dialogues–usually in communities deeply divided over issues that touch on people’s values and worldviews. I have spent much of the last three years working with professors as their classrooms increasingly fit that description. In Jill's terms, I help people wobble, but not fall down. Jill talks about wobble in terms of letting something happen and getting out of the way. That is a piece of it for sure, but there is a choreography to wobble, a delicate but purposeful crafting of space, time, language, movement, and furniture that makes wobble possible. The purpose is to break people out of the conversations that hold us back from seeing complexity in ourselves and others. It is meant to crack the surface conversation to reveal new possibilities, to deepen understandings of values and lived experience, and to unmask our own assumptions. I call it “choreography” because every choice we make while facilitating a conversation invites some responses and discourages others. And every choice we make leads people to focus either on us or on each other. If we call on people, it invites people to raise their hands and wait for us to conduct. If we don’t, it invites people to give and yield focus as they move in and out of the conversational space. It is choreography at its most subtle. If we ask people to sit quietly and reflect for two minutes before answering, we invite the second and third thought that someone has, not just the first. The work of dialogue is disruptive of old patterns. It disrupts dynamics of dominant voices monopolizing the space–including ours. It weakens the power of the first speaker. It breaks the pattern of asking questions we already know the answer to while our students try to read our minds. It invites silence as a space of intention and reflection rather than of fear and disengagement. It invites empathy rather than judgement. It prompts uncertainty rather than certainty and curiosity rather than declamation. It allows for wobble rather than steady motion along the straight and narrow. When I visited Jill’s class, I stood up and talked about dialogue in front of rows of chairs, with people raising their hands and I called on them–ironic. It was a fine conversation. But when I sat down to watch the rest of the class, Jill didn’t just allow or encourage wobble, she choreographed it. Jill asked the students to move the chairs into pairs of arcs facing each other. A wobble happened. Then Jill sat outside the circle. Another wobble. Outside the circle is one of those places that disrupts the old pattern, a place of intellectual humility. It disrupts the pattern of students relying on us for the prompt, the answer, the nod of approval. Then she asked a question she didn’t know the answer to. Wobble. She gave people a chance to reflect before speaking. Wobble. This is not just allowing something to happen; these are a set of choices we make–a choreography that when done right makes possible a new kind of conversation that breaks the dominant polarized and divisive rhetoric or silencing that we see so often in our discourse. What happens when we choreograph wobble is that students rise to their own power and possibility, and move through their own wobbling moments to muster the momentum to move together. In Jill’s class, the conversation had to be interrupted after 40 minutes to announce something about papers, but it would have gone on. Even if Jill and I had quietly snuck out of the room, it would have gone on because the students had turned toward each other and engaged. Whether we recognize it or not, much of our public discourse is designed for simple, polarizing, escalating episodes of attacking and defending well-worn positions. We have opportunities to design and incubate a new discourse, one designed for the generation of ideas, the exploration of new ground, the contemplation of complexity. The patterns we have to break are strong and so our choices must reflect that. Our choreography must reflect the need of this moment; the need to turn to one another with curiosity, complexity, and care.

Ground TransportationAbout a week prior to your travel you will receive an email from Trish Overpeck (overpecp@wabash.edu) with airport shuttle information (pdf). This email includes the cell phone number of your driver, where to meet, and fellow participants with arrival times. Please print off these instructions and carry them with you.

Daniel Madigan, my mentor when I first began teaching Islamic studies, considers his introductory course an opportunity to help students understand Islam as a religious choice and vision. This, in contrast to a politicized framework wherein Islam, is a problem to be solved. Marshall Hodgson also refers to the vision of Islam early in volume one of his series, The Venture of Islam. He writes, “Islamicate society represents, in part, one of the most thoroughgoing attempts in history to build a world-wide human community as if from scratch on the basis of an explicitly worked out ideal.” In an earlier blog post, I recommended the use of graphic novels and comics in teaching Islam because they are substantive and because students benefit from the engagement with visually rich, multimodal texts. Courses in religious studies have an unfortunate tendency toward abstraction. Separating ideas from their cultural expression is a disservice to our students and Islamic or Islamicate culture itself, which represents the “highest creative aspirations and achievements of millions of people;” Hodgson again. If we are to help students appreciate a vision, we must show them how that vision is lived, and the cultural heritage it has built over the centuries. In this post, I want to highlight some of the online resources available through museum websites, particularly the website of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and provide ideas for how these tools could be used in the classroom. In conjunction with a virtual exploration, it would be ideal to send or accompany students on a museum visit but this is not always practicable. Fortunately, museums are committed to education and the advancement of knowledge in their mission statements and their online resources are often exemplary for that purpose. Teaching is sometimes isolating because it can be accomplished in isolation. A busy professor can close off the classroom and get through the term without doing the work of engaging outside institutions. But to do this job right, we need partners whose missions intersect with our own. In my experience, museum professionals are eager to help and they have created a wealth of resources to draw from. A small investment of time spent researching museum offerings or reaching out to a museum education office can pay huge dividends in terms of student learning and engagement. In fact, a more student-driven classroom can save time in the long run. Letting students take charge of their own learning means they are doing more of the work. Anyone who has visited The Metropolitan Museum of Art knows it is an overwhelming experience. Thanks to a sense of direction that allows me to get lost in my own neighborhood, I have spent the better part of an hour just trying to find my way to the right wing in the Met. Their website can provoke a similar experience. It requires a certain amount of detective work to identify the right online resource for your students and a significant amount of scaffolding to guide them to its best use. But there are unique opportunities to be found! Five decades of Met publications are available to search and download, sometimes in their entirety, for free. This collection includes a full online copy of Art of the Islamic World: A Resource for Educators that pairs well with an online lesson plan on “Arabic Script and the Art of Calligraphy” suitable for modified use in the college classroom. The Met website is also home to 82nd & Fifth, a series of two-minute videos in which curators discuss works of art that changed the way they see the world. These videos, including an engaging presentation on the official signature of Süleiman the Magnificent, are also available as part of a YouTube playlist. Projects like this provide useful modeling for classroom activities. A student can be tasked with exploring Islamic art and creating their own short video on how it has changed the way they view the world. The most powerful resource on the Met website is the ability to search its collection as a whole. Students searching for “Islam” will bring up thousands of entries, including photographs, historical information, and links to related objects and textbooks as available. This is a fantastic opportunity but it must be used wisely. Casting students into this sea of information without a clear purpose is not likely to be successful. As a colleague once instructed me, “Throwing everything against the wall to see what sticks is not a sound pedagogical strategy.” Certainly, the Met collection can inform garden-variety research papers and projects begun in the classroom but it can also provide an initial inspiration for detective work. Students might start with an item from the collection and generate questions based on its features and provenance. Finding an elaborate illustration of a drunken party from the Diwan of Hafiz, students may wonder about the relationship between intoxication and mysticism. Confronted with a folio from the Blue Qur’an, they might want to know more about the aesthetic and practical features of other Qur’anic manuscripts. The key is that students are puzzling over museum objects and formulating their own paths of inquiry leading to a more holistic understanding of Islam. Advancing toward the highest, creative and comprehensive level of Bloom’s Taxonomy, you could ask students to curate their own virtual exhibition using an online collection. Seeking out meaningful threads of continuity between temporally and geographically disparate objects is an enormously challenging task but the rewards for a job well done are great as well. Such an assignment, carefully wrought, has the potential to help students consider the vision of Islam as it was realized in material culture; not in abstraction, but as a source of creative renewal and inspiration across time and space.

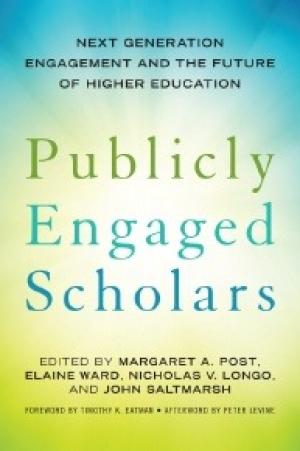

Preparing citizens through education is not a novel idea. Its origins lie in Greco-Roman approaches to the task, and in American history the goal of educating the citizenry can be traced back to Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), William James (1842-1910), and John Dewey (1859-1952). Dewey, who was perhaps the most articulate about the implications of pragmatism for education, saw academic preparation for life in a democracy and the moral education of children as part of the same endeavor. The contributors to this volume acknowledge Dewey’s role in this enterprise, but do not explicitly explain why these essays represent the “next generation” of educators inspired by his vision. The best explanation, perhaps, is that they emphasize academic advocacy, as opposed to broader social wellbeing; engagement with society over preparation for engagement with society; and social location over citizenship as a point of departure for academic work. With that set of assumptions in mind, it is easier to discern the larger purpose of the sixteen essays in this volume which include an introduction and afterward, along with chapters devoted to three subject areas: (1) “The Collaborative Engagement Paradigm”; (2) the work of “New Public Scholars”; and (3) thoughts on “The Future of Engagement.” The vast majority of the contributors to this volume are specialists in education and programs in community engagement, and there are individual writers from the disciplines of art and political science. For that reason, some seminarians and seminary faculty will find more immediate points of contact with their work than others. Both groups will also find themselves asking – if education driven by engagement is appealing or necessary – whether the more natural point of contact for seminaries is the community, the church, or both. A critical evaluation of the essays will also raise other questions to which there are no simple answers: What is the place of “social relevancy and public legitimacy” in shaping the curriculum of higher education (1)? Can engagement as a model for learning set aside more abstract, disciplinary concerns (17)? What role has commodification played in shaping higher education and is learning through engagement immune to commodification (24)? To what degree do faculty members remain accountable to the disciplines that they represent when using engagement as a model for teaching and, if so, how is that accountability achieved? The answers to those questions will all look potentially different in theological schools and seminaries where faculty regularly grapple with the relationship between the work that they do and the needs of the church. Indeed, that realization may point to the most important question that the subject matter, but not the book itself, raises for theological educators: What does it mean for seminaries to engage the church “as reciprocal partners and coeducators” (5)? Answering that question is one that everyone who cares about theological education would do well to answer.

Excellence is seldom achieved alone. These words express one of the major themes of Indigenous Leadership in Higher Education, edited by Robin Starr Minthorn and Alicia Fedelina Chávez. Consisting of autobiographical narratives, the editors and contributors weave a blanket of experiences and guiding principles which illustrate and encourage the involvement of Indigenous leaders throughout the academy. Many of the narratives begin in the traditional manner with the authors situating themselves within their maternal and paternal lines, recognizing the interconnectedness of the present to the past in order to lead future generations well. That sense of community permeates the various narratives, weaving a thread into the blanket of colors that blends the experiences and insights into what constitutes Indigenous leadership. This blend of narratives is most evident in the second and the final chapters, in which the editors succinctly gather individual contributors’ words and correlate them to particular themes that serve as a wheel of knowledge in chapter two and summarize potential methods for incorporation into higher education in the final chapter. In chapter two, “Collected Insights,” the editors provide a wheel of four major components of what constitutes Indigenous leadership. The last chapter highlights approaches and philosophies, strategies, academics, and means of working with students to promote and encourage leadership for Indigenous peoples. While it may be tempting to read just these two chapters because of the breadth contained therein, the narratives themselves expand on one or more of the dimensions discussed in these two chapters. One of the major themes is that Indigenous leadership is communal rather than a solo endeavor; Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy writes that “Indigenous leadership requires individuals to see themselves as part of a unified whole” (53). In chapter two, the editors provide other examples that demonstrate the importance of connection to the community through its elders and the people for whom one serves. Even though most of the narratives are directed toward Indigenous leadership in higher education, many of the principles can be applied to all persons in the academy. The narratives help educators rethink how to provide opportunities for all students to grow in wholeness and wisdom, not just knowledge of facts. Among the qualities the editors describe as “what we strive to embody,” (17) qualities that may resonate with all Indigenous persons, for me, one is clearly lacking. As a Native Hawaiian, I would include gratefulness. While this quality may be imbedded in the concepts of generosity, humility with confidence, and spirituality, I found few expressions of gratitude within the narratives. This disconcerted me because it is inconsistent with what I learned from my kupuna, my Elders. I would hope that, while this embodiment is not expressly evident in the narratives, it is part of their respect for the Elders who have wrapped them in the blankets of experience and provided them with the warmth that enabled them to be Indigenous leaders.