Resources

Research on Student Civic Outcomes in Service Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Methods is the third volume in a series dedicated to research on service learning. This volume, with its timely focus on civic outcomes, is divided into three sections. It begins with an introduction to how student learning outcomes are embedded in service learning, then moves on to various theoretical frameworks by which one can situate research. It concludes with some nuts and bolts aspects of conducting research on student civic outcomes in service learning, defined as “a course or competency-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students (a) participate in mutually identified service activities that benefit the community, and (b) reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of course content, a broader appreciation of the discipline, and an enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility” (10). All three chapters in Part One are useful to the novice in this research area. “Introduction to Research on Service Learning and Student Civic Outcomes” provides a taxonomy of service learning courses, with essential attributes and levels of development for instructors to improve the quality of civic learning opportunities within service learning courses along with clear factors for individual as well as institutional research and assessment. “Student Civic Outcomes in Higher Education” offers a helpful literature review of civic outcomes, while ”Student Civic Learning through Service Learning” concludes Part One with two pertinent questions: (1) What do we know about cultivating civic learning through service learning courses? (2) What do we still need to learn about how the variables of course design influence civic learning? One key point repeated in each chapter is that civic outcomes in service learning should focus on learning with others and not doing for others. Part Two explores research on civic outcomes in service learning through multiple disciplines and theoretical perspectives including social psychology, political theory, educational theory, philanthropic studies, human development, community psychology, critical theories, and activity theory. The chapter “Critical Theories and Student Civic Outcomes” most directly questions the “individualistic” and “server-centered” approach to service learning (184), noting, for example, that serving at a soup kitchen often counts as service learning but protesting does not (187). A critique of the AAC&U Civic Engagement VALUE rubric is particularly thought-provoking on issues of access and power (187-190). Part Three turns more directly to the how-to of conducting research with chapters on quantitative, qualitative, and longitudinal research along with chapters on institutional characteristics and using local and national datasets. One of the most interesting chapters in this section, “Documenting and Gathering Authentic Evidence of Student Civic Outcomes,” asks “What counts as good evidence of learning and for whom?” (303). The chapter identifies two challenges familiar to those who work with assessment: making outcomes explicit and collecting authentic evidence (304-305). Unfortunately, much existing research depends on indirect evidence, and the chapter recommends use of the AAC&U VALUE rubric along with ePortfolios to enable formative and summative assessment. Each chapter of the volume concludes with an extensive reference section. The volume is worthwhile for teachers and researchers who want to improve students’ service learning as a site for civic engagement.

Using examples of community and civic engagement (CCE) at Auburn University, this collection of essays provides readers with a lens through which to view a number of debates in higher education. In the broadest sense, the essays address the question of the role of higher education. More narrowly, they ask questions such as, how do universities respond to increasing public pressure to demonstrate clear connections between education and job placement? Since the volume focuses on civic engagement, authors ask what the ideal relationship between a university and its surrounding community might be. How, for example, does a public university foster such relationships, of what sort, and to what end? With increasing pressure on students to graduate in four years, along with widespread perceptions of higher education as a form of job-specific training, it may seem rather bold for educators to promote a liberal arts education. However, Brunner argues that one can address these questions by looking to the ancient Greek and Roman liberal arts models, which “foster personal growth and civic participation” (1). Through diverse case studies, the authors illustrate the high impact learning experiences that occur in CCE situations. For example, students in political science who do internships have a higher degree of satisfaction with the course, learn nuances about relationships between theory and problem-solving in a community, and often reconsider their career choices. This reconsideration results, in part, from the reflective component of CCE, which helps students make connections between classroom learning and their internships via writing assignments. These connections further illustrate the critical thinking (among other skills) that liberal arts education fosters – skills which align with employers’ desires in hiring. While much of Creating Citizens focuses on teaching and student-learning outcomes, Brunner also addresses the contentious issue of how promotion and tenure committees are to evaluate the work of engaged scholarship. How, for instance, does engaged scholarship measure up to traditional peer-reviewed scholarship? Again, this is not a new question, but one that nevertheless impacts pre-tenured faculty decisions for research plans. Brunner notes that engaged scholarship combines teaching and service, is as rigorous as other peer-reviewed scholarship, and upholds university missions and values by engaging faculty in mutually-beneficial, community-based problem-solving. In short, students, faculty, the university, and the community all benefit from CCE. Readers may wonder how the final essay fits within this volume; though interesting as a reflection on the role of non-native activist anthropologists working in India, the connection to the thematic foci of the other essays is tenuous. Overall, however, this volume would be of interest to educators looking for practical models of CCE that can be adapted to fit one’s own institutional location, mission, values, and vision for community relations. Land-grant institutions such as Auburn explicitly aim to promote application of research, in this case through CCE, a model that any institution of higher education would do well to consider adopting.

As a professor who teaches in an online education program, I picked up this book with interest for how it might inform my pedagogy. The content of the book, while relevant to my context of theological education, addresses more specifically the needs of organizations working for behavioral change in developing countries, particularly regarding available health interventions such as disease testing and immunizations. The authors address the mediums of radio, television, and internet, and how managers of these educational programs can best utilize different types of information sources. Early on, the authors distinguish between “Edu-tainment” and “Entertainment-Education.” Edu-tainment is a focus on education that employs insights from entertainment to keep learners engaged in the educational process and content. Entertainment-Education relies more heavily on the entertainment side in order to teach a certain topic or attitude, helping participants to empathize with characters in order to consider adopting behaviors similar to the characters. Entertainment-Education might look like a fable told to convey a moral – the story of the fable is interesting in itself, while the moral being taught is present but not foregrounded. With Edu-tainment, the same moral or lesson is present as in the fable, but the lesson or intended learning outcome is more directly named. While the title of the book contains “Entertainment-Education,” “Edu-tainment” is the main focus of the authors. Both approaches appeal to the “E Structure,” which is “Engagement of the audience, through Emotional involvement, which inspires Empathy for certain characters, who then provide Examples that demonstrate to the audience how they can accomplish the desired behavior, and also provide a sense of Efficacy for audience members, who make the desired changes or acquire that desired knowledge and gain a degree of Ego-enhancement (personal growth)” (8). Excellence in Edu-tainment requires a great deal of management and collaboration. The authors describe the various formats for Edu-tainment such as video or radio, and how the eventual product should be constructed with a team of writers, producers, and actors, with how lessons should be piloted with control groups to judge their effectiveness. Persons reading this for the sake of improving their online education pedagogy will feel overwhelmed by the expectations here, but learning about the possibilities for dramatic renderings of lessons with scripted dialogue can provide new ways to think about teaching for those interested in deepening their skills. While this book may not be directly helpful to theological educators because of its emphasis on behavioral modification in developing countries, it does provide some helpful tips.

Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education is a well-timed book. Not only are institutions of higher education tasked with preparing students for a globalized and increasingly technically-driven future, many are still reeling from the recession of 2008. According to Smith, these factors push much needed institutional-wide transformation regarding diversity and inclusion from a centralized position to the margins of universities’ priorities. While use of the term diversity in the general study of higher education organizations means “variety in institutional types” (3), in Smith’s volume diversity, infers more. It “refers to historic and contemporary issues of how institutions reflect people from diverse backgrounds and how institutional transformation is occurring with respect to diversity and inclusion for all identities that have emerged as salient in given political, social, and historical contexts” (3). Set in three parts, Smith begins with a section on the significance of context and then directs readers to five fascinating case studies looking at the status of institutional transformation and diversity in South Africa, the UK, the United States, Brazil, and among indigenous institutions in the United States and New Zealand. Last, the editor explores the similar themes, as well as identifies significant differences, which cross-cut the various studies and looks ahead at possible future implications of policy and research regarding diversity and inclusion on institutions of higher education. Perhaps one of the most fascinating, albeit complex, aspects of studying human diversity is not just the great variety of salient identities (race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, religion, abilities, etc.) but also the “increasing awareness that any given individual has multiple identities and that those identities intersect one another” (11). And the significance of one salient identity may differ given the national context. Smith observes that “while race has been central (though different) in both the United States and South Africa” there are places in Africa where “tribal affiliation, language, or religion” may be the more salient social identity among group members (10-11). Institutions are in no way divorced from the complexities and nuances of identity. Smith aptly notes that “institutions reflect the cultures, norms, values, and practices” of the people in the institution, “the historical and social circumstances in which institutions are developed,” and they “reflect the stratification and values of the larger society” (13). This also means that institutions easily replicate the dominant systems of social stratification and inequality if they are not careful. However, if they are intentional and committed to connecting diversity with the core values of their institution, they can “act as catalysts for change” (13). Jansen’s chapter on the complexity of institutional transformation in South Africa addresses the many boundaries still blocking Black students’ access to previously White universities, despite the end of apartheid. Jansen recommends seven fundamentals of deep transformation on a racially divided campus and walks readers through the treacherous terrain of the difficulties which South African institutions have faced. As the first Black Vice-Chancellor of the Free State, he has witnessed radical changes on South African campuses and provides some valuable insights for dealing with deep-seated suspicion between White students from conservative Afrikaans homes and Black students from political African homes. Both parties feel victimized and, while many of the students did not live through apartheid, Black students often “feel the legacies of those apartheid troubles in their personal circumstances” and many White students feel the need to protect the Afrikaans language and see the university as an “ancestral home” (38-39). The challenge for leaders like Jansen is balancing reform and reconciliation. Eggins’ chapter on institutional transformation in the UK addresses a half-century long upheaval in which the diversity of institution type played a significant role in the quest for diversity in higher education. Polytechnic schools developed in the 1960s and created a binary system of education. In 1992 “almost all polytechnics, together with a number of higher education institutions” were made into universities, to create a more unified educational system (47). Eggins maps out various “theoretical approaches to institutional diversity that address diversity and mission vertically and horizontally” (47). One of the most compelling aspects of this chapter is the author’s review of the effects of equality legislation on institutions of higher education in the UK. Moses’s chapter on the challenge of diversity for leadership in the United States offers readers clear and powerful suggestions on how institutions must reframe the case for diversity. She also enumerates five ways US institutions are linking their institutional goals to the value of diversity and provides readers with ways to think about diversity as it relates to other institutional core values. This chapter is pragmatically focused and makes an excellent resource for those in leadership positions within higher education, especially those challenged by “the institutional inertia that often pushes back against this kind of difficult cultural and institutional change” (69). Another poignant example of the varied and unique contexts in which institutions of higher education find themselves is illumined by Neves’ chapter on diversity in higher education within Brazil. As in the UK, equality legislation plays a significant role in Brazil’s embrace of diversity. Since the 1930’s, Brazil has been plagued by “the myth of racial democracy” which attempted to mask the overt racism (104). It took a new Brazilian Federal Constitution in 1988 which “defines racism as a crime” to legally recognize the work of social movements (especially among Blacks and feminists in the country) towards diversity and inclusion in Brazil (104-5). Although the Constitution “ensures free schooling at public institutions” only about one-tenth of Brazil’s higher education institutions are public (106). A highly competitive selection process which requires written exams (vestibular) means a majority of those admitted into the free schools hail from the best high schools and from the higher socio-economic classes (107). Neves expounds on the many programs implemented to help bridge the inequality gap, including access to “pre-university entrance exam cram courses” for African descendants and indigenous peoples, scholarships for low-income students, and support for projects that “produce knowledge on ethnic-racial themes” (109). Parker and Johnston look to indigenous institutions for insights into how universities can meet standards of academic excellence while honoring the culture and traditions of diverse populations. As they so aptly note, “education is not a neutral or objective concept” (129). Institutions of higher education are not value-free zones. They reflect the “societal norms established by the dominant group” (129). Often, merely by “carrying out their academic mission as usual” these institutions end up “perpetuating the very inequality and marginalization that higher education institutions seek to overcome” (130). In the US, tribal colleges and universities “must combine western and tribal paradigms for the success of their students” (133). In New Zealand, indigenous institutions (known as wananga) are theoretically and practically informed by “Maori knowledge, pedagogy, and philosophy” (136). Indigenous institutions take intentional steps to create environments which support their students and community members as well as prepare their students to engage in world markets often dominated by western cultural values. Institutions of higher education around the world could learn a great deal from their example. As disparate and unique as the institutions of higher education (HEIs) in these case studies are, Smith does an excellent job highlighting themes that cut across all of them. For each, historical and national context matters and even if race matters in all contexts, race matters differently in different contexts. The intersectionality of identities is complex. HEIs are reacting to expanding globalization, increasingly rapid changes in technology, fiscal austerity measures, and the political mood swings prevalent in public policy debate. There is hope, however. If HEIs are challenged in many of the same ways, perhaps they can learn from one another as well.

As much as teachers would like to argue to the contrary, the university is a business, an educational business to be specific. Universities, colleges, technical schools and the like are in the business of selling learning. They sell this product to those who see the need for education beyond the formative years, whether that be training in a trade or preparation for an occupation such as medicine, psychology, or religious service. Institutions of higher learning have been in existence for around a millennium, and have served as a tent pole artifact for institutional culture – universities have either set the bar of cultural progression or have fallen behind, sputtering to keep pace with the practitioners outside their hallowed walls who are establishing new trends and raising the bar set by the university. We seem to be in a contextual epoch that is squarely set between each of these extremes. There is still a hushed reverence that comes from finding a peer who attended Harvard, Stanford, Princeton, or Emory. Many in the academic community clamor to hear special lectures from Continental colleagues who have attended or are employed by Oxford, the University of Paris, or the University of Amsterdam. In some pockets, simply having a college or graduate degree can still mean higher pay, positional advancement, or advanced social standing. In the United States, we seem to be living in a time of both saturation and scarcity. Higher learning institutions are continually creating new and engaging programs to prepare interested individuals for securing employment in an ever-evolving, technologically-driven, globally-emerging marketplace. And yet the number of students seems to be shrinking as many weigh the cost of attending college or find that their career choice may not even require a college degree. Responsiveness to the changes taking place in society and academic preparation for those changes is of concern for leaders at universities, colleges, and trade schools. On one hand, the administration crunches numbers and devises business strategies to ensure that the institution remains open. On the other hand, faculty craft courses and develop programs to ensure that teaching is what keeps the institution open. This is the discussion that editors Leisyte and Wilkesmann present before the reader. Assembling over twenty scholars from across the globe, this volume demonstrates that the New Public Management model can be used to successfully organize institutions of higher learning. In providing specific examples from Germany, China, the UK, and the Netherlands, as well as individual authors speaking out of their own experiences, this volume shows how academic managers can integrate business-based operational models with rubric-based educational models to promote academic integrity and marketplace relatability. Change will continue to be the one true constant of the educational universe, and this volume provides a good map for the road ahead.

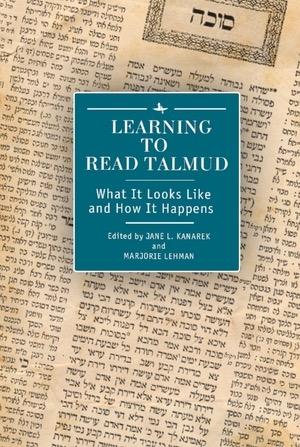

The subtitle says it all. This is not a how-to book that will teach one how to read the Talmud, but a book on how to teach others to read the Talmud. It is part of a “growing field of the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), a field that seeks to expand the research agendas of scholars in a particular discipline to include research into the teaching or learning of that discipline or both” (xii). Each chapter is written by a different instructor of Talmud, all of whom have various methods and goals for teaching Talmud to their students. While the title might sound like it severely restricts its audience to those who teach Talmudic students, it doesn’t. Insofar as the book examines various methods for teaching a text that is both ancient and in a foreign language, the book could be useful for anyone who teaches primary texts, especially primary texts that involve a foreign or dated language. The book does not advocate a particular method of teaching or approach to reading the Talmud, recognizing that the best method and approach would depend on the goals of the class and the students’ previous exposure to Hebrew in general and the Talmud in particular. Some of the instructors focus more on the technicalities of the languages, such as Berkowitz and Tucker. Others, such as Gardner and Alexander, focus more on how one teaches the text to non-specialists. Kanarek examines the role of using secondary readings to understand the primary text in teaching. Whatever one’s style of teaching or goal for a primary text in a foreign language, one can find various ideas for how to implement them in the classroom. Each chapter gives a brief background as to the intent and assumptions of the instructor, specific examples of what was done, student feedback or responses, as well as post-class reflections. Berkowitz discusses the usefulness of study guides for assisting students in asking the right questions about grammar and vocabulary to aid their understanding and make technical terms seem less alien. Tucker exemplifies in his approach how to help students appreciate and not gloss over difficulties in the texts. Kanarek examines how different types of secondary readings can help students in different ways discover and appreciate issues in the texts. Gardner considers how explaining the narratives and surrounding culture aids non-specialists in understanding and appreciating the texts. Alexander structures her class to help students appreciate the possibility of more than one answer. All in all, this book offers some very practical ideas on teaching original and foreign texts.

Early adopters of instructional technologies, for years, have been trying to raise awareness of the need for theological education to be adaptive (never mind innovative--that just seems not in the DNA of most theological schools) to the emerging realities of learning in higher education. Many have been warning that "the Digital Natives are coming!" Well, the Digital Natives are here, and as a result, most theological schools are obsolete; they just don’t know it. That is, the way most theological schools teach is obsolete. Students have changed, and as a result, so has the nature of education and learning. Here are some characteristics of the incoming students in seminaries (adapted from Beloit Colleges "Mindset" lists): They are the sharing generation, having shown tendencies to share everything, including possessions, no matter how personal. Having a chat has seldom involved talking. Their TV screens keep getting smaller as their parents’ screens grow ever larger. Rites of passage have more to do with having their own cell phone and Skype accounts than with getting a driver’s license and car. A tablet is no longer something you take in the morning. Threatening to shut down the government during Federal budget negotiations has always been an anticipated tactic. Growing up with the family dog, one of them has worn an electronic collar, while the other has toted an electronic lifeline. Plasma has never been just a bodily fluid. With GPS, they have never needed directions to get someplace, just an address. There has never been a national maximum speed on U.S. highways. Their favorite feature films have always been largely, if not totally, computer generated. They have never really needed to go to their friend’s house so they could study together. They may have been introduced to video games with a new Sony PlayStation left in their cribs by their moms. A Wiki has always been a cooperative web application rather than a shuttle bus in Hawaii. They have always been able to plug into USB ports Their parents’ car CD player is soooooo ancient and embarrassing. Since they binge-watch their favorite TV shows, they might like to binge-watch the video portions of their courses too. “Press pound” on the phone is now translated as “hit hashtag.” The water cooler is no longer the workplace social center; it’s the place to fill your water bottle. There has always been “TV” designed to be watched exclusively on the web. Yet another blessing of digital technology: They have never had to hide their dirty magazines under the bed. Attending schools outside their neighborhoods, they gather with friends on Skype, not in their local park. They have never used Netscape as their web browser. “Good feedback” means getting 30 likes on your last Facebook post in a single afternoon. They are the first generation for whom a “phone” has been primarily a video game, direction finder, electronic telegraph, and research library. Electronic signatures have always been as legally binding as the pen-on-paper kind. They have largely grown up in a floppy-less world. XM has always offered radio programming for a fee. There have always been emojis to cheer us up. Donald Trump has always been a political figure, as a Democrat, an Independent, and a Republican. Amazon has always invited consumers to follow the arrow from A to Z. In their lifetimes, Blackberry has gone from being a wild fruit to being a communications device to becoming a wild fruit again. They may choose to submit a listicle in lieu of an admissions essay. By the time they entered school, laptops were outselling desktops. Once on campus, they will find that college syllabi, replete with policies about disability, non-discrimination, and learning goals, might be longer than some of their reading assignments. Whatever the subject, there’s always been a blog or a Youtube channel for it. A movie scene longer than two minutes has always seemed like an eternity. As toddlers, they may have taught their grandparents how to Skype. Wikipedia has steadily gained acceptance by their teachers.(1) Closer to home: The majority of your incoming students have taken at least one online course, in elementary school, high school or college; they don't need a "tutorial" or orientation to using an LMS (but many of your Faculty do!). A paper syllabus is useless to them. They expect that most of the information they need for your class will be on a digital platform (an LMS, a website, or an app) on a screen (a laptop, a tablet, or their phones). Whatever they produce in your class, for whatever subject, will be digital to some extent. And, they are better at Powerpoint than you. The reality is that as theological schools we hold on to an industrial-aged model in a digital world. Furthermore, the imagined future students we push our admissions office to find to fill our classroom seats and residential halls don’t need us to learn. Classroom instruction as a signature pedagogy is obsolete. That may seem an overstatement, but here are examples of how Digital Natives challenge ideas of how you learn and from whom. At 13 Patrick McCabe learned robotics from the internet. He even demonstrates how to teach a robot to learn. Amira Willighagen was seven years old she took it upon herself to learn how to sing opera music. Growing up in Pakistan, there were no instructors in town that could teach Usman Riaz how to play percussive guitar, so he learned it from the internet. "I wanted to learn more about that so I just let the internet be my teacher," Usman said, "You learn from exposure and you learn from watching other people and that's exactly what I did except that instead of having the person physically in front of me I had a portal to them through the computer." He says, "There's so much out there available for everybody that they don't need to sit and worry about whether they don't have a teacher or not, you just need an internet connection and the desire to want to learn something and that's really it." Arguably, the most important role of a dean is to be the visionary that shapes the educational values and enterprise of the school. Does your vision for your school align with the realities of a digital world? Is your Faculty teaching in the ways Digital Natives need to learn? Expect to be taught? Is your Faculty preparing ministers with skills for a world that no longer exists? Is your Faculty as attentive to the ways of teaching and learning as much as they are to what they teach? Will your next incoming class find they've signed on to an industrial age system of education that is obsolete? Where is your school situated in the landscape of online theological education? (1) Adapted from Beloit College's "Mindset" lists.

We can define the syllabus with precision, but our best-laid plans are subject to the moments when life simply happens. Questions arise. Frustrations are felt. And the sages on the stage better have something to show for all their high-falutin’ learning. At least this is how I feel when teaching in the midst of traumatic events. I can usually triage the syllabus—shuffling assignments around to give space to the moment. I even know well enough to leave room for the inevitable crisis within my course planning. But what do you actually do when you’re in front of students who have come to class just as raw as you? There’s no media bulletin that will solve the problem. Trauma doesn’t care about public relations. There’s no master lecture that will bring a master solution. Trauma doesn’t leave room for satisfying answers. But I’m here to tell you that all is not lost. Every Christmas break, I go home to Houston. My most recent trip was the first time I had been since Hurricane Harvey. And in the days following my return to Pennsylvania, friends wanted to know what I saw. I didn’t have much to respond with except for the watchwords of the human story. We rebuild. We heal. We grow. We learn. This is what we do in the face of natural disaster. It too is what we can do in the face of psychosocial trauma. But it’s going to take some time. Unfortunately, I have found myself in the position of consulting a number of institutions enduring the perpetration of prejudicial affronts, most frequently concerning rampant sexism, homophobia, and racism. The biggest mistake I see is the grab for a big fix or antidote to make the situation go away. I have to explain that trauma is an immediate crisis that takes hold of us for the long haul, so our job is to equip our communities to rebuild, heal, grow, and learn as best as we can manage, moment by moment, day by day. For teachers, this means reminding ourselves and our students that the more we know, the better we can manage the crisis before us. When life happens, I tell myself to adhere to the following protocol step by step. Gather your composure. Find your footing even in the midst of your insecurity. Claim your own humanity—the right to feel, the right to hurt, the right to grieve. Eat nutrient-rich foods. Drink plenty of water. Meditate, do jumping jacks, practice yoga, or walk around the block. Your first step is to regain your sense of self. Reconnect. Take a moment to let a trusted colleague or companion know that you’re about to go into the fray. You have a community. A simple text message or phone call can remind you that you’re not alone. Lower the bar. When it’s go time, your job today is to “be you” and “do you” with the students. This will equip them with the confidence to do the same. Before you know it, you will fall back into the role of teacher. They will fall back into the role of student. And you’ll together develop a new stasis. Preach what you have practiced. Have your students take a few minutes to do a version of what you have just done. Lead them in a moment of silence or even a quick stretch-break. Let people grab a drink of water and return to class. Let them check in with each other as they trickle back into the room. Your acknowledgment of their humanity will go a long way in garnering the trust you’ll need for the day. Teach the moment. Present what you understand about the situation and contextualize it in light of what you know as teacher-scholar. Then take a few moments to show how you’re learning. In so doing, you’ll remind students that they are not the sum of their emotions. They are also learners with skills and proficiencies to help them grapple with the day beyond what they could have done prior to class. It also solidifies a basis for community-building amidst the new state of affairs. From here, you have a “we” with which to work. Come together around a whiteboard and make a list of questions that you all want to pursue as a class. Name the resources you might consult in the coming days in your search for more information. Excavate your syllabus to see not whether there’s anything of use, but what can be used in the moments ahead. Better questions lead to better possibilities. The work you have put in—together— will bear fruit in the days to come. I know now what else to ask for in the midst of trauma. But until then, use the learning process as a vehicle to position yourselves in renewed strength and community.

In our ostensibly secular age, discussing the real-world contexts and impacts of religious traditions in the classroom can be difficult. Religious traditions may appear at different times to different students as too irrelevant, too personal, or too inflammatory to allow them to engage openly with the materials, the issues, and each other. In this “Design & Analysis” article Aaron Ricker describes an attempt to address this awkward pedagogical situation with an experiment in role-play enacted on the model of a mock conference. This description is followed by four short responses by authors who have experimented with this form of pedagogy themselves. In “Conplay,” students dramatize the wildly varying and often conflicting approaches to biblical tradition they have been reading about and discussing in class. They bring the believers, doubters, artists, and critics they have been studying into the room, to interact face-to-face with each other and the class. In Ricker's experience, this playful and collaborative event involves just the right amount of risk to allow high levels of engagement and retention, and it allows a wide range of voices to be heard in an immediate and very human register. Ricker finds Conplay to be very effective, and well worth any perceived risks when it comes to inviting students to take the reins.

One page Teaching Tactic: working in groups to practice reading carefully and write academically.

Wabash Center Staff Contact

Sarah Farmer, Ph.D

Associate Director

Wabash Center

farmers@wabash.edu