Resources

When asked, “What was Muhammad’s moral character like?” Aisha replied: “His moral character was the Quran.” Students encounter this hadith at two moments in the introductory course to the study of Islam. The first is when students meet the Prophet Muhammad through hadith literature, the written record of sayings and actions of the Prophet. We return to the hadith the following week when students begin to explore the Quran. In our second pass of this famous narration, we begin to contemplate what it means to say that the Prophet’s character was the Quran. The idea that the Prophet was a walking Quran is at once simple and simultaneously beyond the immediate reach of the class. Students explain that to say the Prophet’s character was the Quran means he exhibited ideal virtues. This exegesis grasps at an accessible meaning of the hadith, but does not yet appreciate the concept of embodied knowledge that is so important in classical Islamic education, especially Quran education. In some respects, the notion of embodied knowledge runs counter to the kind of education students embark upon in their college years (and the whole of their education leading up to college). Most students describe the purpose of their liberal arts education as a training in a particular way of thinking—honing the skills of critical reading and analysis. But perhaps the idea of embodied knowledge is not so foreign to them. The university where I teach emphasizes “hands-on” and “experiential” learning, the power of doing to facilitate learning. Students are encouraged to study abroad, take on internships, and generally roll up their sleeves and immerse themselves—physically—in their education. So, there are some comparisons to make with students as we discuss the idea of what it might mean to embody the Quran. In this way, the institution’s learning philosophy translates to our classroom in my effort to create for students an embodied experience of the Quran. One of my goals when I teach the Quran is to develop in students an appreciation for the Quran beyond its written text (the Quran as mushaf). I emphasize the significance of the recited Quran and the place of recitation in Muslim life. As I introduce them to the art of Quran recitation, I try to create an auditory experience for the class. In doing this, I aim to cultivate an aesthetic appreciation of the recited Quran. This is an ambitious goal, one that deserves some probing. What kinds of possibilities and limitations might there be in cultivating an aesthetic appreciation for the recited Quran in the (secular) liberal arts classroom? To introduce the Quran to the uninitiated through its recitation is, first, to invite the audience to listen. Listening is itself an act to be honed. To prepare students for the auditory experience, they learn about the significant place of memorization (ḥifẓ) and the art of enunciation and elocution (tajwīd) with patterns of melody (maqāmat). Even with this preparation, the listening we try to practice in our class is complex. Just as much as opening the Quran and reading a page of text cannot convey its meanings, neither can listening to the most beautiful of recitations. In my effort to cultivate for the uninitiated an appreciation of the aural experience of the Quran, I try to create an opportunity for them to recognize its beauty. But this beauty may not be accessible to everyone. My hearing-impaired students have urged me to consider more deeply what an aural attunement to the Quran means for the deaf. For hearing students, the question of what it means to listen to the Quran can be overwhelming. In their preparation to listen, I share various sources with them (readings by Michael Sells and Kristina Nelson, as well as videos of Quran recitations where audiences physically and vocally respond to the performance). So, when students are not moved by a Quran recitation, they describe a sense of feeling left out. For them it is like standing in front of the Mona Lisa and grasping to understand its power. The Quran itself situates ways of listening in relation to the recognition of its truth. While the Quran describes hearing as a physical perception of sound, hearing is typically associated with spiritual understanding. Indeed, the Quran insists that listening requires the heart. Hearing is sutured to learning and understanding, whereas those who reject its message are described as those who “do not hear,” and those who are “deaf,” among other sensory descriptions. In one passage, those who reject God’s message are described as putting their “fingers in their ears” (2:19). At other moments, God interferes with hearing, such as when God placed “heaviness in their ears” (18:57), and “a seal upon their hearts so that they do not hear” (7:100). To listen, then, is not limited to creating an auditory experience for hearing students, but one that involves the heart. Or to put it in less anatomical terms, hearing in the Quran requires a recognition of it as revelation. In this way, the goal of cultivating in students an aesthetic appreciation of the Quran may be at best naïve and at worst problematic. Listening to the Quran for delight, pleasure, or entertainment may be an invitation to over-aestheticize the Quran—to dissolve its message into mere beauty. Listening to the Quran does not allow for a distanced observation. It immerses the listener, all listeners, in an embodied experience. While Quran recitation offers an opening into the Quran in ways that might awaken students’ interest (since it offers a break from the written word and involves their senses that are so often neglected in liberal arts classes), it is through recitation that those who hear and those who do not are distinguished by their bodies and beliefs. To expose students to the significance of the embodied Quran may be to invite them to the edge of its beauty.

I was born and grew up in the hills of east Tennessee, in the Appalachian region of the United States. As a child, I didn’t realize that where I lived had a reputation in other parts of the country. I also didn’t know that I had an exceptionally strong Southern accent until I was in college. When I decided to pursue academia, I worried that my accent would lead others to think that I did not belong in graduate school. I began to attempt to erase my accent, especially during classes or when speaking to a professor. Before giving my very first paper at a conference, I practiced over and over again to be sure that I sounded “smart” and “professional.” It was becoming clear that, to many people, “Southern” and “smart” were not synonymous. When I moved to the “north” (New Jersey) for my doctoral studies, these fears increased. I worked to prove that I was smart and capable, which meant that I attempted to hide my accent, even though it wasn’t as strong as when I was younger. Even with all of my work and practice, it occasionally slipped through and inevitably someone would comment on it. Through reading and reflection, I now realize this struggle with my accent was connected to my background and, further, my class. While many of my fellow students seemed to understand academia instinctively, I struggled to grasp it. This imposter syndrome affected me in numerous ways, especially in graduate school. Even when I had a question or a comment, I was nervous to speak. Insecurity infiltrated my body; I would wring my hands under my desk, cross and uncross my legs. When I finally found the courage to speak, my face would redden with every word. While I have worked to overcome these feelings and now can speak in academic settings, I still vividly recall my embodied experiences as a woman from Appalachia navigating academia. A number of scholars have written about class as it relates to the academy and the classroom.[1] For example, Stephanie Moynagh writes about the ways that class affects embodiment. She observes: Embodied experience varies widely, always shaped by the pervasive impacts of power structures that affect different bodies in different ways. Making sense of our somatic experience is also influenced by cultural discourse and by the limitations of cognitive processes of understanding. . . Membership in identity categories such as working-class, working-poor, poverty-class, low-income, or cash-poor is also confusing because class-based experience and identity can shift dramatically over time.[2] These observations resonate with my own experience in academia, a space that I continue to carefully navigate based on my background. My embodied experience also affects my pedagogical approach to the classroom. I remember vividly how it felt to enter a university classroom and feel out of place, confused at some of the language being used, and worried to contribute to a class discussion. I now recognize that my experiences navigating the academy help me to be a better teacher and guide for my students.[3] While my southern accent is now (mostly) hidden, I do not enter the classroom assuming that everyone understands terminology. Instead, I define words and set expectations clearly from the first day of class. As Moynagh argues, “All learning environments, both formal and informal, need to make meaningful space for nondominant ways of knowing and relating to the world.”[4] For this reason, I also offer a variety of ways that students can participate in the class. Instead of only acknowledging vocal contributions or sophisticated vocabulary, I encourage silent reflection and journaling. Similarly, offering creative assignments within the classroom is a strategy that can help to ease the tension for students who are less familiar with academic writing. I use storytelling often as a teaching strategy. Storytelling is popular in Appalachia, where we hear stories from our parents, grandparents, and even our neighbors. When possible, I take the students outside or arrange chairs in a circle as I tell a story, usually a biblical or historical one (because of the courses that I teach). I have found that students remember these stories later into the semester. In these ways, my geographical background becomes a way that I mentor and encourage students. I now acknowledge my Appalachian background when possible and attempt to dismantle harmful assumptions about geography and class. [1] bell hooks, Where We Stand: Class Matters (New York: Routledge, 2000); Matt Brim, Poor Queer Studies: Confronting Elitism in the University (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). [2] Stephanie Moynagh, “Class and Embodment: Making Space for Complex Capacity,” in Sharing Breath: Embodied Learning and Decolonization, ed. Sheila Batacharya and Yuk-Lin Renita Wong (Edmonton: AU Press, 2018), 356. [3] For an example of the ways sharing our own experiences can positively affect student learning, see: Phil Bratta, “Relating Our Experiences: The Practice of Positionality Stories in Student-Centered Pedagogy,” College Composition and Communication, January 1, 2019, https://www.academia.edu/43453027/Relating_Our_Experiences_The_Practice_of_Positionality_Stories_in_Student_Centered_Pedagogy. [4] Moynagh, “Class and Embodment: Making Space for Complex Capacity,” 365.

The seminary professor, a man of color, just walked out of the academic dean’s office. He had been teaching at the mainline Protestant theological institution for eleven years. The academic dean, a white woman, called him into her office to talk about a recent article he published in a mainstream magazine. He had written about white supremacy within American Christianity and the manifestations of racism in Protestant churches, including in churches that supported the seminary. The dean noted that she had received several complaints about his article. The professor asked the dean if she disagreed with anything that he wrote. She evaded the question and changed the subject to how the professor might repair relationships with some donors. She also reminded him that his review for promotion was coming up shortly and that she worried how this “controversy” could disrupt the review. The conversation ended with no resolution, but the dean said they could revisit “next steps” in a day or two after some prayer and reflection. The seminary professor was enraged, exhausted, and frustrated. In a word, he felt defeated. The professor began teaching at the seminary immediately after graduate school. He loved teaching his students and especially appreciated the increasing racial and ethnic diversity within the student population. But over the years, the racism that he experienced, and the racial harm that he witnessed his colleagues and students of color encounter, had taken a deleterious toll on his wellbeing and health. Being called into the dean’s office was the latest in a long series of episodes in which he and other colleagues of color were assailed because of what they taught, how they advocated for students of color, and how they challenged their institution to live up to its moral, pedagogical, and spiritual commitments to racial diversity, equity, and inclusion. In recent years, seminaries throughout the United States have grappled with racial discrimination. At some seminaries, there have been a handful of discriminatory incidents whereas at other schools the problems of racial prejudice have been widespread. Immediately after departing the dean’s office, this professor sat down on a bench outdoors and wrestled with whether his meeting with the dean was racially discriminatory. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission states that “it is unlawful to harass a person because of that person’s race or color” and explains that “harassment can include, for example, racial slurs, offensive or derogatory remarks about a person’s race or color, or the display of racially-offensive symbols.” The law does not forbid “simple teasing, offhand comments, or isolated incidents that are not very serious,” but it also outlines how racial discrimination is “illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment or when it results in an adverse employment decision (such as the victim being fired or demoted).” The professor acknowledged to himself that the meeting may not have fallen into the legal delineation of harassment, but he knew it was racially harmful and he could feel the pain coursing through his body. The professor concluded that he had three options. The first option was to compromise and agree to a plan to talk with some of the offended donors. He would not apologize for his scholarship, but he would discuss his article with them and listen to why they thought he was wrong. The second option was to seek the support of his colleagues of color. The faculty of color had confronted the administration before, and he believed they were prepared to do so again on his behalf. The professor thought that his resistance might also garner media attention and perhaps he could write another article for the magazine explaining what happened. But the professor was weary. He thought about his health and his family. He did not know if he, or his family, had the energy required to enact the second option. Therefore, the professor was strongly considering the third option, which was to simply resign from the seminary. He would miss the classroom dearly, for it was his sanctuary, his refuge, and a holy site where he experienced rejuvenation through the wonder of learning together with his students. But in this moment, the professor did not know how much longer he could bear the pain in his teaching body. Questions What does this case study tell you about the seminary and how it engages matters of racial diversity, equity, and inclusion? What would you do if you were the professor? Are there other options the professor should consider? If you were the academic dean, would you have done anything differently in this situation? If so, what? If not, why not?

During my first year of teaching, I participated in a Faculty Learning Community that was designed especially for first year faculty. At one point during our bi-weekly gatherings, one of the facilitators made the comment, almost in passing, “We teach humans, not subjects.” My brain shifted gears. His statement helped me place the student in center view instead of the subject and content of my teaching. He was from the education department, so it made sense to me that he was bringing us back to pedagogy. His admonition was that we must first and foremost attend to the humans before us. The moment has stayed with me as an ongoing question—what does it mean to consider and teach the human before me, first, and my course subject, second? There are a couple workshops I have participated in that have helped me fill this in further—one on culturally-responsive teaching that builds on research in neuroscience and cognition, and another on what’s called small teaching. In themselves, these are full and rich frameworks with corresponding research and publications. Still, there are a couple key, practical, contributions they have made to my teaching that have stuck with me and help me keep the human brain in mind—and where my understanding of embodied teaching begins. The first key learning about the brain is that it cannot learn when its amygdala is activated (often referred to as the reptilian brain). The amygdala is activated by stress, anxiety, anger, hunger, fear. It is instinctive, unconscious, and controls our basic body functions, increasing our heart rate and blood flow, for example, when it senses danger. If/when our amygdala is triggered enough, it can keep us in a guarded state that makes it hard to stay open enough to learn. My students’ ability to trust me, then, at least to trust me enough so they can stay relaxed enough to learn becomes my first order of business as I attend to them as whole human beings. Attending to their amygdala is important for them to be ready for the actual task of building on their knowledge and stretching their brains as I invite them to reflect critically upon religion—which is an often-fraught subject that raises people’s defenses. This is where my learning about “small teaching” comes in—specifically the beginning and end of class. The first and last five minutes are key for easing students in and out of the learning space. I am very intentional about how I start and end the class. At the start of the class, especially at the beginning of the semester, I make sure to cover a few bases: (1) give them something to do so that they have a productive way to channel any anxious energy; (2) humanize myself to them so that they can begin to trust me a little; and (3) let them know they are allowed and encouraged to take care of themselves in our classroom so they know I respect them as autonomous beings. I have a variety of ways to communicate these things to them, but I will paint a picture here of a common scene from day one in my typical classroom. As students enter the classroom (whether physical or virtual), a slide is already posted for them to reflect on relating to the topic of the day that includes an image and two questions: What do you notice? What do you wonder? This gives them something to do while also bringing them to the present moment. Then as I call us together to start the class, I welcome them and ask if anyone has a story to share about some recent good news or something new or fun they have done recently—there are usually one or two brave souls who are willing to share about their new pet or job or recent trip. This helps us all get a glimpse of one another as who we are outside of the classroom space. It lightens the mood a little. Finally, right before we start our discussion, I let them know that they are free to move around, stretch, do what they need to do to be comfortable in the class—they can even walk out if needed. I want them to know that I respect their autonomy and support them doing whatever they need to do to be well and to stay present in as much as it is possible. Those are the first five minutes, where I try to help us arrive to the present moment and also try to build their trust so they are willing to hang in there when ideas get challenging. Then the last five minutes are crucial for helping students integrate the day’s learning and give their brain a chance to wrap things up. I never end my class with announcements or reminders—those come earlier—instead I end with a reflection exercise that gives them an opportunity to review, synthesize, or make note of any lingering questions they can bring to the next class. The point is to not send them out with an activated amygdala or hurl instructions at them at the last minute. And having the class end on a calm note is a way of setting the tone of “We got this, we are good for today, and we will continue next time.” As they walk out of class is when they most often reach for the snack box. In my in-person classes, I always bring a box of snacks that has at least three kinds of bars in it (cereal bars, protein bars, granola bars). From day one I let them know that our brain does not learn when it’s hungry and I want them to be able to learn, so they can always count on the box of snacks. In a way, my approach to teaching the human starts with attending to both the brain and the stomach —because it really is all connected anyway… right?

As a toddler, the Grammy-winning musician esperanza spalding heard Yo-Yo Ma play cello on Mister Roger’s Neighborhood and decided she wanted to play music like that. In an interview, she said it was Ma’s “total body activism during the music” that captivated her. A jazz-bassist, vocalist, and composer, esperanza moves with her music, which defies genres, and hopes to create a physical experience of resonance in her audience. As a professor of practice at Harvard, she hosts jam sessions at the studio at Harvard’s ArtLab so that participants can improvise and make music together. In her heart, she wants to be someone in “deep co-learning” with her students. How can our classrooms be spaces of co-learning that welcome creativity, collaboration, and even improvisation? How can we recognize the body as a valuable site of learning, so that the knowledge we gain would not be over our heads, but would speak to and touch our innermost yearning and desires? If this is difficult to do in an in-person classroom, is there any hope for online teaching via Zoom? Last spring, I taught an online course on Spirituality for the Contemporary World for Master students and community learners. I have learned so much about embodied teaching and learning: guided meditation, listening to music and poetry, art appreciation, rituals, Tai Chi, cross-cultural discussion, and much more. I want to reflect on a few memorable moments from the class. I invited Professor Cláudio Carvalhaes to speak on “The Pandemic and the Re-imagination of Rituals” because I knew him to be a creative teacher, preacher, and liturgist. Carvalhaes discussed the relation of ritual to our body and earth. He shared his experiences of leading workshops on liturgies on four continents of the world, which led to the book Liturgies from Below. At a time of crisis, he said, it is important to draw from the experiences of the community to craft liturgies and prayers that respond to the people’s needs. At the end of the presentation, he invited students to offer prayers with the movements of their bodies. He explained what he was going to do and invited students to warm up by standing, shaking loose, moving from side to side, and turning around. He demonstrated how to do these to ease the students. Then he picked up his guitar and sang four stanzas of a song. As he sang the first stanza on happiness and thanksgiving, he invited students to move to embody memories of happiness and joy. Similarly, he sang the second stanza on sadness and the third one on anxiety and invited students to imagine movements to express them. In the final stanza, he closed by asking God to hear our prayers, which were all in our bodies. During the pandemic, feelings of grief, helplessness, and uncertainty are stored in our bodies, as the book The Body Keeps the Score says. Acknowledging these feelings through movements of prayers helped us to connect with these emotions. Doing this together made us feel less alone. Students appreciated the time with Carvalhaes as they were given the freedom to experience the power of ritualizing through their embodied selves in their own ways. I also invited Episcopal priest and artist the Rev. Susan Taylor to lead a class on spirituality and art. Some years ago, I invited her to speak in my class in person and she brought a lot of art supplies with her. She wanted us to try out and create a collective art project at the end and the process was inspiring. This time, I told her, the class was online and I would appreciate it if she could include doing art in the class. She told me to ask students to have their art supplies, such as painting and drawing mediums, brushes, pieces of paper, color, palette knives, etc., on hand. She made a presentation on how arts help individuals and churches during a time of pandemic and strengthen our relationship with God. She shared photos of her art and included a detailed explanation of the process of working through a 7’x 6’ painting entitled “Skyflowers.” Introducing the process of how we would make art together, she offered a lot of encouragement for us to explore and tune out the self-judgmental voice. On Zoom, we could see her painting in her studio, adding shades and layers of colors to her work. We spent some time creating our own art and afterward we shared our experience of making art and what this meant to us. We also discussed how to include art in our own spiritual life and ministries. The brief moment of creating art transformed us from spectators to participants. It was wonderful to see students trying to express themselves in new ways and hear what art evoked in them. Since the class met for an hour and a half in the evening, I decided to teach Tai Chi movements for several minutes in the middle of each class. I began by teaching simple Tai Chi exercises so students could understand the principle of balancing Yin and Yang in the movements. I also posted a video from YouTube so that they could follow the exercises if they wanted to practice more. After we practiced these exercises in several classes, I was able to teach them several Tai Chi movements by breaking down the steps. Even though we practiced only a few minutes in class, a student was motivated to learn further about the practice of Tai Chi. We easily succumb to Zoom fatigue in online classes when teaching is didactic, usually with a PowerPoint presentation, and students become passive onlookers. But there are many ways to expand the possibilities of sensory experiences, even in a Zoom meeting. esperanza spalding invites us to think about teaching as embodied adventures. I have been stretched and learned so much from my co-learners.

We were halfway through the first day of class when a student started viciously criticizing a TED talk I had just shown. It wasn’t hard to determine where the student’s criticism was coming from. He was furious that I would consider a woman worth listening to. He was spewing misogynistic hate in a room that was 70 percent female. On the first day of class. I responded to the student’s misogynistic rant in my usual way. Trying to stay calm, I seized on something he was saying I could spin into a statement I agreed with, interrupted him with a “yes, and,” and proceeded to explain the value of the points made by the woman in her talk, being sure to emphasize how important and insightful they were. I never heard a misogynistic word out of him again. He never mistreated his female peers (I monitored closely) and by the end of the term was thoughtfully engaging with readings by female authors. It probably helped that he was surrounded—in my class alone—by thirty brilliant young women who were living proof of women’s intellectual capacities. It also helped that I was a white male, in a position of authority, who had not let him get away with saying misogynistic things unchallenged, even if I did use a strategy inspired by nonviolent conflict transformation techniques rather than direct confrontation and criticism. This story illustrates the power of embodiment, even in the form of a video. I doubt assigning a book or article by a woman would have elicited the same visceral reaction. Honestly, it usually takes me strategically getting a little angry in class to get students to stop routinely misgendering authors as “he,” despite my best efforts to ward off that habit, including through strategies like making cover pages for PDF readings that include a short biographical statement on the author. We often think of “embodiment” in teaching as referring to the kind of presence the teacher has in the classroom. Perhaps we also need to find ways to apply embodiment strategies to the authors we assign. Do we lose some of the power of a diverse syllabus when the authors remain just names on a page? In my classes, I try to use media to help highlight the diverse array of voices I hold up as worth listening to. Sometimes I assign a video or podcast or invite a guest speaker in person or on Zoom, but since most of the assigned readings are books, individual chapters, and articles, I also find other ways to help my students see our authors as real people. I often weave short videos or clips of lectures by our authors into my lessons. Lacking those, I’ll include a photo of an author alongside a quotation from their work in a slideshow. These aren’t complicated interventions; however, I fear that without them my students miss the diversity in my syllabi. This is perhaps most true of those students who most need to see it, those so steeped in patriarchal culture that even a “Barbara” or “Maria” becomes a “he.” Such interventions might not be the best idea if the message your reading list sends is that your field is dominated by cishet white men or that they are the only ones worth listening to, reading, or studying. Applying embodiment strategies to authors assumes that we’ve already done the work of diversifying our syllabi with the voices of those whose gender identity, sexual identity, racial identity, ethnic identity, nationality, language background, disability, age, religion, socioeconomic status, etc., both reflect the full diversity of humanity and affect their scholarship. As a white male, I don’t often deal with the kinds of challenges to my authority and expertise other educators experience, at least not from my students (as an adjunct, administrators and my tenure-track colleagues routinely devalue my expertise and experience). This means that my embodiment in the classroom is not particularly fraught. If anything, I have to take care not to be too intimidating lest my presence stifle participation. My identity and positionality also give me a platform and a responsibility to challenge worldviews that dehumanize and devalue those whose backgrounds, identities, and experiences are different from mine. Making the authors in my syllabi a little more real for students is one small way I pursue that goal.

One of the cruel ironies of teaching in Atlanta is that the so-called fall semester always begins in the damp-flames-of-hell climate that is August in Georgia. But this morning, as I sit with my coffee on my back porch, I recognize the halting, modest signs that a proper fall may arrive after all, despite all evidence to the contrary. I see a few yellow leaves drifting to the grass from the weeping cherry tree. Likewise, I notice the tip top of the Japanese maple tree is hinting at its fall purple-red glory. The air, while still sticky, carries a whisper of crispness. I could sit here for a while, if I can just slow my mind and let my senses help me pay attention to the world. Embodiment should come easily to me. I am a practical theologian whose specialization is the relationship between theology, education, and ecology. This intersection can hardly be imagined absent a strong commitment to embodiment, to the ways in which we understand our bodies to inhabit particular places and relate to other bodies; to see, to breathe, to taste, to hear, and to touch. In honoring the body’s knowledge, we name its vulnerability, and the ways in which we are tied to the vulnerability of other bodies.[1] I have tried to counter false narratives that would suggest that a real academic somehow transcends her embodied self. I have developed practices to help ground me in my heart and body, and when I’m able to commit to these practices, everything else seems to flow: my research, my teaching, even those administrative tasks. Easier said than done, though. In our institutions of higher education, serious inquiry has been conflated with dispassionate objectivity, learning with the cognitive work of recalling and interpreting.[2] We might even struggle to recognize the needs and honor the knowledge of our own bodies, as individual scholars and human beings.[3] Speaking for myself, I might spend hours crouching at my computer, loathe to break my supposed focus. With high hopes, I might have scheduled a workout or a walk with the dogs for later in the afternoon, only to abandon those plans when it seems I do not have time. I might eat breakfast and lunch at my desk. Now, after two years of remote work and learning, I think the question of embodiment is insisting itself to us in new and powerful ways. I think we begin to find our way toward an answer by first looking within. How do you begin your day? Environmental education scholar Mitchell Thomashow writes, “Consider two different ways of greeting the day. You can step outdoors wherever you may be in order to feel the temperature, wind conditions, light, sounds, and smells, or whatever visceral impressions fill your senses. Or you can immediately glance at your phone to check your messages, email, or whatever virtual information gets you oriented.”[4] On good days, I might begin the workday at my writing desk at home, which faces out a window, and quietly work on research and writing projects for an hour before the rest of the family awakens. Sometimes I might check in online with some colleagues who also arise early to write before turning to our other daily tasks. It’s a tiny act of resistance to the culture of accelerated and sometimes frenetic work demanded by the pressures facing so many of our institutions.[5] But more often than I would like to admit, I start my day by checking my institutional email on my smart phone before my feet even hit the floor. It’s a seemingly small thing, but the net result is that, from the start, my mind is in a reactive state. I respond to every demand, every email, every knock on my door, with little sense of purpose or vision. I end the day exhausted, my eyes and shoulders strained, with seemingly little satisfaction to show for it. This way of being is not sustainable, of course. And as orientation approached this fall, I was confronted in a new and urgent way with the limitations of approaching my work without mental and emotional intentionality. Even deeper, I was confronted with the poverty of the life of the mind absent a steady, trusting, and grounding practice that honors my own body’s knowledge. Thanks to a benign but persistent virus that took up residence in my inner ear in August, I found myself unable to be in crowded spaces, to process complex visual or aural stimulation, to look at my computer screen, or even read without becoming very dizzy. I would clench my jaw and “power through” whatever task was before me, practically racing back to my office to close my eyes—no fluorescents, please!—or rest my head on my desk until the next thing. I barely got my syllabus revised and was grateful for a colleague who volunteered to build my course website for me. To my surprise, though, I could work in the yard, walk the dogs, and even do yoga with little difficulty. The body that found itself queasy and unsteady after just twenty minutes of looking at my computer screen was calmed and centered by these practices that grounded me in sensory experience, slowed my mind, and allowed room to reflect, think, and be present. Embodied practices that I once had perhaps too eagerly broadcast as a countercultural “choice” became a necessity and a source of salvation. As I write this, episodes of dizziness and disorientation are, happily and as expected, becoming less frequent and less severe. Yet I am clinging to a reordered pattern for the morning, landing me here, on my porch, greeting the day with all of my senses, watching the leaves turn and listening to a chorus of birds and bugs. There is so much to do, it’s true. But might you also find a place to pay attention to the world, and your body’s place in it? A place where you could sit, just for a while? [1] Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (New York: Verso Books, 2004), 26-27. [2] Furthermore, the ways in which learning is structured in so many of our institutions reveal a disembodied “implicit curriculum” observable in how our classrooms are arranged, the kinds of assignments we make, and the reduction of embodied exercises and classroom breaks to reluctant “accommodations” we make so that the mind can continue the work of learning, unencumbered by the inconvenient needs of the human body. See Elliot W. Eisner, The Educational Imagination: On the Design and Evaluation of School Programs (New York: Macmillan, 1979), 97. [3] It is, of course, important to acknowledge that “embodiment” has historically carried additional risks for too many scholars and students in institutions with unexamined racist, sexist, and heteronormative assumptions. See, for example, Carol B. Duncan, “Visible/Invisible: Teaching Popular Culture and the Vulgar Body in Black Religious Studies,” in Being Black, Teaching Black: Politics and Pedagogy in Religious Studies, edited by Nancy Lynne Westfield (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2008), 3-15. [4] Mitchell Thomashow, To Know the World: A New Vision for Environmental Learning (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2020), 75. [5] Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber, “Introduction,” in The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 1-15.

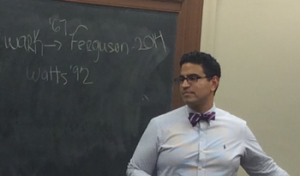

Elias Ortega-Aponte, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Afro-Latinos/a Religions and Cultural Studies Drew University As I geared up to teach two social justice themed courses this Fall, my summer preparations were disrupted by the news of two tragedies and the reflections they prompted. First was the death of Omar Abrego, beaten to death by police on August 2 in Los Angeles. Witness reports claim that Abrego was taken out of his car and beaten up by two police officers for at least 10 minutes, and left in a pool of blood. The father of three would die hours later in a

“I’m just so sick of feeling awkward,” I told my spouse the night before the first day of classes this semester. After having taught for eight years in another school across the country, I was about to begin teaching at a new institution. I was bemoaning the fact that everything was different at my new job, and I felt like a fish-out-of-water most of the time. My new colleagues were extremely warm, welcoming, and supportive. But I was still learning the ropes at my new institution. I had to ask questions about nearly everything: how to use the copy machine, if I could use the coffee maker at the end of the hall, how to navigate the learning management system, and who to go to on campus for what. I was also feeling unsure about the new age range of students I’d be teaching. I had been at a small graduate school, comprised of adult students (generally ages 40-70), and I was now at a medium-sized liberal arts institution, teaching mostly undergraduate students (typically 18-21 years old). I hadn’t taught undergraduate students since I had completed my PhD, over 9 years ago. When I was chatting about my nervousness with a friend, she consoled me by saying, “You’ll be fine. Just don’t dress frumpy!” So, when I was getting ready for work on the first day of classes, I went to my closet in search of my least frumpy ensemble. I donned a brightly colored geometric-print skirt and a pair of 3-inch heeled sandals in hopes that my students, over twenty years younger than me, might approve. My first two classes that day went well. I introduced them to the syllabus and assignments, but also sprinkled in some course content. I also tried to introduce them to my teaching style, by using music, 1-min journal writes, and a think-pair-share exercise. By the third class of the day, I was getting into the groove and feeling more confident, which means I began to walk around in the classroom. Then, right in the middle of class, when I was near the front of the room, I stumbled. I lost balance on my right foot—remember: I was wearing 3-inch sandals—and then tried to regain balance by putting all of my weight on my left foot. The next thing I knew, I was tripping around the front of the class and flailing my arms in big circular motions until I went crashing into the whiteboard behind me. The only saving grace was that my skirt remained in place. When I regained my composure and looked up, the 24 students in the room (nearly all of whom were first-years) were staring at me wide-eyed, their mouths gaping. One cried out, “Are you okay?!?!?” I managed to mumble a joke about them not expecting an acrobatics performance in a theology class, but it had no effect. No one laughed. They were, I’m guessing, still in shock. I had to keep talking and teaching, because what else could I do? After class (thankfully my last class for the day), I headed back to my office. I passed my new colleagues in the hall, and did what any self-respecting introvert would do: When they asked me how my first day went, I smiled and said, “Fine!” Then, I went into my office, closed the door, and posted about it on Facebook. The next day, I could laugh about it (and could also tell my new colleagues about it). I laughed about it with my students, which gave them permission to laugh about it too. And now that we are almost at the mid-term mark in the semester, I realize, like most awkward and humbling experiences, there’s a teaching and learning moment in this one too. Here’s what I learned: 1) Embrace the awkward; it may help in relating to students. Even before I fell, I was feeling awkward, but I’m guessing that many of my students were too. As first-year students, it was also their first day of class in a new institution too. Some students had to present me with sheets verifying their learning accommodation needs, which, based on societal stigmas, they might not have preferred to do. Others, I later learned, were first-generation college students and were wondering if they belonged on campus. And a few were single mothers, trying to balance a full course load with parenting and part-time jobs. When I stopped worrying about how I looked and felt, I could be more in tune with their needs. 2) Think about how to help first-year students succeed in a new learning environment. I had been learning the ropes in a new school, but so had they. Many had left home, family, friends, and partners, and they were living away from all of their most stable relationships. They were also learning to manage their time and new freedom. Realizing this, I decided I could do more than simply list on my syllabi the contact information for the Student Success Center. I set some time aside in the course schedule for supportive activities. For example, I had a representative from the Student Success Center come into class and talk about the services they offer; I asked a librarian to demonstrate the research database to them; I led workshops on how to avoid plagiarism, how to read critically, and how to write a theology paper. I also passed around informal evaluations after the first few weeks of class, and I learned that students were feeling nervous about disagreeing (even respectfully) with other students in small groups. So, I led another workshop on respectful, critical dialogue. 3) Be comfortable. I’m back to wearing flats and 1” heels, even if they are frumpy. But it’s not just my shoes that have to feel comfortable, I have learned. So does my teaching style. When I over-plan or am too calculated about what I want to do in any given class session, the delivery usually falls flat (pun fully intended). When I relax, loosen my grip on the lesson place, and let the feel of the room and the students’ questions and concerns guide the way I present the material, it usually works much better. The students are more engaged and take on a more active role in their learning. Have any of you had big embarrassments in the classroom? If so, I’d love to hear about them—not just to stroke my bruised ego, but to hear what you’ve learned from them too! Please comment below.

My teaching goals reflect my expectations that my students will change the world. I want my students to have profound consciousness of love, of themselves as capable beings, of the beauty of creation. I want to instill in them with the necessity to fight for the oppressed, uplift the downtrodden, and conspire with the voiceless for a place in the societal decision-making. I want them to be cunning enough to avoid the shallow passions of those who would exploit their talents, squander doing good, and misuse their power. I want them to be wise. With these ideals in mind, I design into every syllabus the notion of the body. There are few things more sacred and more political than the human body. Intentionally engaging the body to learn, while simultaneously making the politics of the body part of the course conversation, is a critical way to get to my lofty teaming aims and kindle my student’s passions. Wisdom depends on the body. A metric I use to assess in-class learning activities is the degree to which I have engaged all the senses of the body in a semester. If, by the end of the semester, I have not engaged all the senses multiple times and in multiple ways, I deem my cache of learning activities for that course as weak. When I engage all the senses multiple times throughout the semester, I notice students’ depth of understanding is higher. I carefully design activities for seeing, smelling, touching, hearing, and feeling, not because of student’s varied learning styles, but because a multisensory encounter is more interesting and is more satisfying to the curiosity. Giving adults permission and opportunity to learn with their bodies is an act of resistance against the current body politics which would deem the body only as a commodity. And it’s more fun than just sitting still. I am well versed in shaping courses that point to and analyze the ugliness of the hegemonic politics. A notion which oftentimes intrigues my students while studying the politics of the body in the USA is the ways our bodies are used as indicators of inferiority and superiority. It is thought that to gaze upon a body, one can determine who is male, white, straight, and wealthy. Continuing, it is also thought that to gaze upon a body one can determine who is female, not white, not straight, disabled, and poor. This delusion is perpetuated by the bad science portrayed on some TV shows. There is an episode of CSI where the coroner, while investigating a crime scene, uses a caliper to measure the width of the nose of a charred body and informs the detectives that the deceased victim was African American. Disputing this kind of ignorance about the body and race/gender/class/sexual identity politics is the stuff of marvelous classroom discussions. This semester I wanted to shape a course and a conversation that was a teaching of love, self-worth, dignity, acceptance, and belonging for the personal body, for bodies of knowledge, and communities as bodies of persons. The course is entitled “Reading Deeply.” I selected one book for us to read for an entire semester. The book we are ruminating over is Remnants: A Memoir of Spirit, Activism, and Mothering by Rosemarie Freeney Harding with Rachel Elizabeth Harding. It is a multi-genre memoir that vividly demonstrates an integrated life of deep spirituality and activism. I want my students to be exposed to the wisdom of this text in hopes that they will emulate this wisdom. A thematic thread in the memoir is of healing, wellness, and care for the body. Pressing students to deeper engage body/identity politics, the first assignment is to create a wellness plan and fulfill that plan throughout the semester. Students reported-in about their plan last week. While each woman was making her report (all the students are women), the other students listened with remarkable tenderness. There was an air of respect and regard as each woman told us of the focus of her plan, the rationale for the focus, and the activities she would pursue over the semester for healing, fitness, balance, and rest. The projects were about living into their best selves by disrupting the patterns of ignoring, abusing, or neglecting their bodies. The plans included stopping some habits and starting new habits. In all cases the women were excited about being given course space to consider her own body and contemplate the question, “do you want to be well?” Asking students to live-into the principals of our reading rather than just “think about” the reading is their preference for learning. Their reporting felt reverent. At the end of the semester, they will report-in again telling the story of attempts at self-care and healing. The political is always personal. In studying the harm, violence, and inhumanity of identity politics it feels right, needed, even provocative, to teach students to value their own bodies, to respect the enfleshed. The power of love to create a more humane world undoubtedly includes care of self, nurture of body – a tending to the soul. In the memoir (pp 39-40), Rosemarie recounts the words of her mother after recovering from a near-death experience: “…. Listen, Rose. When you die, there is nothing, nothing there but love. Everything else is gone.” “Hmm.” I listened. “Nothing but love,” she said again. “So while we’re in this world, we have to do whatever we can to love people, to love this world, to take care of all that’s in this world. Because that’s all that matters, the love.” I closed my eyes briefly. The impact of my mother’s words made me sway ever so slightly where I sat. “Hmm.” She was ready to get into bed. She was pulling the covers over her shoulders when she said it to me again, “Now don’t forget, Rose. There’s nothing left but love. That’s the most important thing. That’s what you need to know.”