Resources

Elias Ortega-Aponte, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Afro-Latinos/a Religions and Cultural Studies Drew University As I geared up to teach two social justice themed courses this Fall, my summer preparations were disrupted by the news of two tragedies and the reflections they prompted. First was the death of Omar Abrego, beaten to death by police on August 2 in Los Angeles. Witness reports claim that Abrego was taken out of his car and beaten up by two police officers for at least 10 minutes, and left in a pool of blood. The father of three would die hours later in a

Travel Information for Participants Already Accepted into the WorkshopGround Transportation: About a week prior to your travel you will receive an email from Beth Reffett (reffettb@wabash.edu) with airport shuttle information. This email includes the cell phone number of your driver, where to meet, and fellow participants with arrival times. Please print off these instructions and carry them with you.

Creativity can be learned, practiced, and matured. Encourage yourself to ask - "why not?" "what if?" and "suppose ....?". Be brave in your teaching, suspend judgment, and learn to listen inside and outside of yourself. Dare to learn inspiration as a skill. Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield hosts Dr. Delvyn Case (Wheaton College: Massachusetts)

Before the quarantine caused seismic interruptions, a cloistered education was deemed by many as the better education. This longstanding approach to education meant that the student would sequester from the world, study undisturbed from the goings-on of the world, to then emerge and return to the world as a learned person. The time away from society, family, and many kinds of communal obligations was meant to provide time for intellectual maturation, contemplation, and some say, an extended adolescence. The students would be free to read, write, and think while under the watchful eye of a teacher. In the cloistered model of education, the degree taken (wrestled and snatched) afforded the recipient a select spot in the ranks of the higher echelons of society. The focus of education as secluded and separate from society is evident in the language of students. Students talk about the classroom as being “in here” while their lives are “out there.” Students, in rebuffing some ideas, comment “that won’t work in the real world” or “that’s nice to discuss, but in the real-world people will not go for that.” The classroom, for these students, is not the real, while life in society, in community, with family obligations and responsibilities is the real. Students also signal that what is taught in many classrooms has little relevance to the problems and pain of their people. Or what they learn requires a great deal of translation, interpretation, and adaptation to be relevant to the suffering of their people. The primary aim of cloistered teaching is to insulate student and teacher until which time that the student has met the disconnected standards of the faculty. In this time of shifting models of education, these kinds of new questions abound: Suppose the aim of education is not to hide from the world in order to emerge as an educated person, but instead the better aim is to prepare to meet the needs of the world as education? Could this moment be forcing us to a collective realization that the better aim of education is to engage in the world as education and thus change the world? What is the relationship between communities of learning and social change? What is the influence of the world upon classroom teaching? Moving forward, what will be the relationship between communities of learning and the world? What will be the relationship between schools and the very neighborhoods, towns, and cities they occupy? What if the world is the classroom? What practices of communities of learning are needed for social innovation? What meaning-making practices, understandings and joys of the world are needed to facilitate vibrant learning in schools? Yes, many schools have forms of internships, field education, supervised vocational experiences, elaborate field trips, or study abroad while in a degree program. Most of these programs are auxiliary to the degree program and if not auxiliary the experiences which keep students in the world or send students into new worlds are not the spine of the curriculum. The primary presumption of current models of higher education is that student’s first learn theory in a classroom (cloistered), then are sent out into the workplace to practice. There is still a separation and privileging of theory over practice. Howard Thurman informed us years ago that theory and practice are each sides of the same coin. What would it mean to create approaches to education which do not separate theory from practice or student from community? A small start to answering this critical question has to do with the mindset of the students while in a degree program. The identities and social locations of my students has always been a significant factor in my teaching. I wanted my students to come to class and bring with them into the course conversation the joys, suffering, trouble, practices, learnings and know-hows of their people, their communities. I believed that students, to have agency in their own learning, must not leave their families nor society for education, but they must reflect critically and imaginatively on the struggles of their community looking for new and needed solutions. To facilitate this approach, I designed this learning exercise for my introductory course: During the second session of the course, I asked students to reflect upon these questions: (a) Who are your people? (b) What sacrifices did your people make for you to be in this educational experience? (c) What problems plague your people? What problems have their backs against the wall? Once these questions were engaged, I would instruct them to draw a metaphor or simile to depict your people and their current social situation. I chided them not to reduce the complexity of the situation, but to use a metaphor which depicted the complexity. I gave them time to think and draw. Finally, I asked these questions for further reflection and preparation for our semester long conversation: (a) What kind of leader will you need to become to assist your people and relieve their suffering? (b) What leaders will you join for the thriving of your people? Using their drawings and prose we created a gallery wall in the classroom. I encouraged them to, for the entirety of the semester, keep their families, churches, neighborhoods at the center of their experience in this degree program. Throughout the course I insisted that they not think generically nor individualistically as if they were at school alone or disconnected from the world. Throughout the semester I led them in other learning activities and assignments where they had to continue to consider the specific problems, troubles, challenges, and attributes of their people and ways our study informed those troubles and fostered their leadership formation in their own context. We do not have the luxury of disconnecting our best minds from the troubles and support of their families and neighborhoods while undertaking higher education. We need models of education which nurture interconnection, understands community and promotes a sense of belonging as a necessity to healthy society.

Driftwood on a beach. How did it get here? From where? When? Why this beach? Why this day? And also, that it arrived, on the foam, with a bounty of neon green moss, stubbornly shining a light in the soggy sand. A beacon. Life will out. Blog originally posted in April 2018

As religious and theological educators, one way to encourage democratic formation among our students is to teach about democracy, especially about the historical relationship between religious institutions and democracy. Another way is to provide opportunities for students to practice democracy. In other words, we might consider how our classrooms and assignments can provide opportunities for students to engage in democratic practices. Both seem important to democratic formation among students. In the United States, one way to describe a civic association, religious institutions having historically been the largest share, is a school of democracy. While this Tocquevillian view has its critics, social scientists claim that participating in civic associations can cultivate a set of civic beliefs, dispositions, and practices that will contribute to a robust civic life. For example, participation in civic associations can generate citizens’ ability to care for one another, care about public issues, and learn how to deliberate about these public issues. They are also thought to generate what Robert Putnam calls “social capital,” which is created when citizens learn the norms of reciprocity, build networks, and build trust. Social capital is needed for citizens to come together to work on common projects, build broader cross-group networks, and join together to hold elected officials accountable. What makes something—an institution, organization, workplace, classroom, or community—democratic? I recently discussed this question with a student as she prepared to facilitate the week’s discussion of Jeffrey Stout’s Blessed are the Organized. As we discussed the text, she compared two organizations she has worked for. Transparency and shared decision-making were features that she felt made her current organization more democratic than the other. Practices of shared authority, shared responsibility, transparency, and accountability are all part of what organizing people democratically looks like. Providing students with examples and theory helps them evaluate the organizations and institutions that they are currently a part of or help lead. It can also cultivate their moral imaginations as they envision reforms or their broader vocation. Further, teaching students about the civic and democratic practices of religious institutions is fundamental to cultivating a moral imagination. Churches played a significant role in the grassroots organizing of the Civil Rights Movement, for example. Our students should not only study the moral reasoning that motivated this civic work but also the organizing practices and the principles that structured these movements. This includes analyzing instances of undemocratic authority and accountability within movements, such as the gendered disparities within certain spheres of the Movement. Contemporary examples are crucial too. C. Melissa Snarr’s All You That Labor is an ethnographic study of the role that religious organizations played within the Living Wage Movement. In addition to being a more contemporary example of broad-based organizing, this study illustrates how religious institutions can help frame the moral language of a public issue. This, too, seems important for helping students develop a moral imagination and prophetic voice. Teaching about democracy, however, is not the only way we can imagine our role as theological and religious studies educators. Rather, our classrooms can also be places where students are able to practice democracy. In my ethnographic study of a public high school in Brooklyn I found several examples and a robust culture of shared authority and shared responsibility among teachers and students. I borrow this way of framing democratic education from Amy Gutman, but it is also deeply related to broader traditions of liberative or critical pedagogies. In my spring course, I incorporated a practice of shared authority and responsibility. Students were divided into small groups of five to six and each was responsible for facilitating the discussion for one week. I met with each student prior to their day of facilitation, and during class I observed. This structure, I believe, is one way to share not only authority with students but also to share responsibility. Students are authorized to share in the responsibility of how the learning unfolds not only with the professor but also with their colleagues. To make these aims more explicit, I asked students to complete a short feedback form after each discussion. One of the questions was: How much more do you feel you understand the content after the discussion? Students could rate on a scale of 1-5 with 1 being “about the same as before” and 5 being “much more than before.” Another question was: How collaborative was the knowledge production and discussion? Students could rate on a scale from 1-5 with 1 being “little to no collaboration” and 5 being “very collaborative.” My goal was to make the aims of the discussion clear: collaborative knowledge production. In this way, I hoped to cultivate a shared responsibility among the group members for understanding, critiquing, and applying the week’s content. While some students incorporated this language and framing into their written feedback, I could have done more to incorporate this as a practice central to the aims of the course. As I reflect on how to revise this practice, I am eager to incorporate other ways to practice shared authority and responsibility within the classroom.

Getting through the pandemics will take all of us, plus the willingness to allow our imaginations to be chaotic and refuel the soul. Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield hosts Dr. Christine Hong (Columbia Theological Seminary).

Creating worthwhile experiences for students using a digital platform can provide new, interesting and creative options in teaching. Cultivating the digital imagination will help teaching into the future. Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield hosts Kwok Pui Lan (Candler School of Theology - Emory University).

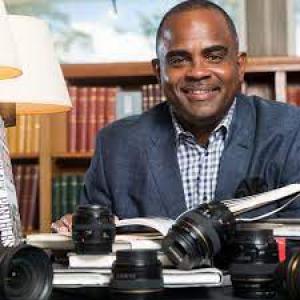

I can’t afford a boat but I can rent one. I spent a day on the water with my wife, Dr. Vanessa Watkins, her sister Dr. Adriana Higgins, and my brother-in-law, Rev. Michael Higgins. This time with family and friends doing something out of the ordinary, inspires my creativity. I had never been out on a pontoon boat before and never driven a boat; but, here we were having fun, laughing, talking and enjoying each other. It was one of the most relaxing times of my life. I cannot quantify how this might have affected my creative energies, but I know it did. A big part of being creative is enjoying life, having fun and relaxing. When we are able to relax, we allow our brains to rest and be restored to create. I encourage you as a teacher, professor and creative to make time to do new things with family and friends. It will bring joy to your life and invigorate your creativity. Caption: My family and me on a pontoon boat in Red Mountain State Park, Ackworth, GA. ©Ralph Basui Watkins