How Can We Bring Our Students’ Cognitive Load Down?

Like most of my colleagues, I’ve noticed a sharp drop in my first-year students’ writing and reading skills during the pandemic. And they are unfocused. Forget herding cats—trying to keep a classroom of first years on topic now feels more like herding bumble bees. More of them skip classes or disappear altogether. And of course, they struggle with depression and anxiety.

Mental health, focus, and academic performance are interconnected, and the problems feed each other in messy and complicated ways. But I suspect that increased cognitive load plays a key role.

The pandemic increased the cognitive load for all of us in three significant ways:

- It disrupted our routines, forcing us think carefully about tasks that we otherwise do on autopilot.

- Fear and uncertainty increased our anxiety, and anxiety makes it harder for us to process information effectively.

- It added a number of new tasks and distractions.

Students are dealing with that and more:

- Their job is learning, and to help them do that, they have several professors. But since their professors also suffer from cognitive overload, students are getting more confusing directions, less clear feedback, and more last-minute changes than they normally would.

- Since students are academic novices, they are less capable of putting the intellectual skills they are learning on autopilot. They have to think about each step.

- And let’s not forget the cognitively, socially, and emotionally demanding task of starting college.

It’s too much at once.

As long as excessive cognitive load operates as a confounding variable, we won’t know what’s causing our students’ problems. We need to help students bring their cognitive load down, both because it causes suffering and because bringing it down will help us identify and address the other significant problems.

So how do we do that?

Not by dumbing things down. But we often unintentionally create unnecessary cognitive load for our students. They end up working on unimportant things.

And so, here’s my big teaching question for this summer: What unimportant things am I making my students think about, and how does that distract them from working on what matters?

To address this, I’ll focus on three different areas:

- Reduce anxiety and uncertainty about my course and about grading.

First-year students spend way too much energy trying to guess what we want, and they often guess wrong. And that makes them spend way too much time and energy on unimportant things. I’m going to revise the rules for my classes over the summer, making them as transparent as I can. In the fall, I’m going to explain them more clearly and more frequently. I like my students to get a headache from all the deep thinking they do in my class, not from worrying about how to format their bibliography or about whether a bad paper grade will mean that they fail the class (it won’t).

- Use lots of routine and repetition to let my students put as many basic tasks on autopilot as possible.

I’ve been resisting too much routine and repetition because it seems boring, both for me and for them. But I think it will go a long way towards reducing anxiety and cognitive load, so I’m going to use more of it this fall with my first years:

- I’ll consider making all reading assignments due on Tuesdays and all writing assignments due on Thursdays.

- I’ll use a single simple set of instructions for all papers and one for all informal writing.

- I’ll ask the same three questions about each reading: What is the author saying? What do you think about it? How does it connect to our other readings and discussions?

- I’ll start each class in the same way: How are you doing, really? Put away electronics (unless you have special permission), you need your book, notebook, and pencil, here’s the plan for today.

- I’ll end each class the same way: Please write down a takeaway and a question from today; here’s the assignment for next class, come talk if you have questions.

- Include fewer details.

Eliminating course content is painful. We love our disciplines, and we want to include key distinctions and nuances, those beautiful and intricate details. So we keep packing things in. But as much as it pains me to admit this, my first years don’t need to learn the correct way of citing Plato and Aristotle (Stephanus and Bekker pages be damned). They don’t even need to know what a Stephanus page is. They need to understand basic MLA and they need to know why one cites sources.

Eliminating details in our instructions is difficult because students mess up in so many ways. It’s tempting to include all the ones we’ve come across so far. But detailed instructions are counterproductive because our students simply cannot process ten unfamiliar and challenging things at once. I’ll include two or three crucial ones.

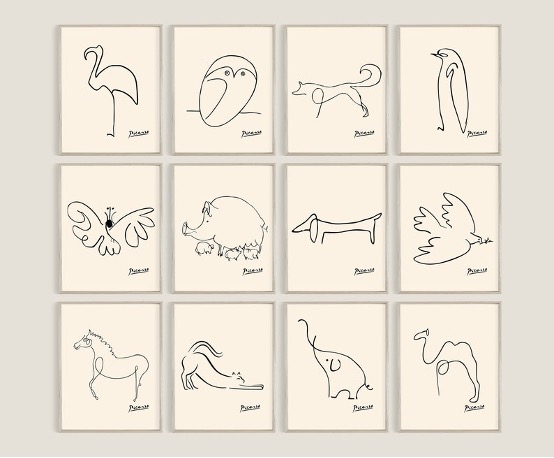

A friend just introduced me to Picasso’s animal drawings. Each captures an animal with a few simple lines. There is no background, no detail, no color, but they are crystal clear and impossible to misunderstand. I want to teach like one of those drawings.

Further resources

Jarrett, Christian. 2020. Cognitive Load Theory: Explaining our fight for focus. BBC. (I draw on his analysis above.)

Brief overview of the differences between novices and experts here.

Picasso animal drawings here.

Two of my blogs: How to provide feedback on papers and how to use nudges.

Leave a Reply