Teaching in Times of Ferguson: A Personal Reflection on Social Justice Pedagogy in a Theological School

As I geared up to teach two social justice themed courses this Fall, my summer preparations were disrupted by the news of two tragedies and the reflections they prompted. First was the death of Omar Abrego, beaten to death by police on August 2 in Los Angeles. Witness reports claim that Abrego was taken out of his car and beaten up by two police officers for at least 10 minutes, and left in a pool of blood. The father of three would die hours later in a hospital. The reports were unclear as to the reasons that led to Abrego being stopped that evening, the details of his beating, and his death. A week later Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager, was left to bleed to death in the middle of a street in Ferguson, Missouri, after being shot by a police officer who claimed to have feared for his life - leaving me to ponder how the fear of an armed white police officer is reason enough to claim the life of a black youth. These were but two reminders of the vulnerability of Black and Brown peoples in the United States, two more victims in too long a list of those who died in acts of police brutality over the last few years. These tragedies, and the communal responses to them, led me to rethink, yet again, about my own body, and about my body in a pedagogical space, and about my practices as a social justice educator.

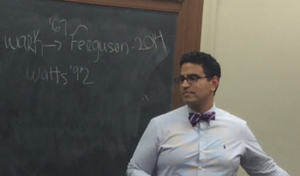

Two questions drive my reflections here. The first is how my body signifies in a classroom in times marked by these unfolding contentious events and what these events reveal about our societal dealings with questions of race and racism. In current times, it is not only that the renewed public relevance of matters of race and the everydayness of violence against people of color call for ongoing critique of systemic structures of oppression and the pervasiveness of micro-aggressions people of color endure everyday. It is also that these structural inequalities and micro-aggressions shape the pedagogical space and influence pedagogical choices. Theological schools are not immune to the distorting influences of structural inequalities and micro-aggressions. The underrepresentation of faculty of color in theological education, and the experiences of isolation they report, point to the possibility that pedagogical spaces for theological education are, more often than not, hostile contexts for faculty of color to live out their teaching vocation.[1] Meaning that faculty of color in theological education deal on a daily basis with the combined effects of unequal structures and forms of micro-aggressions inside and outside of the classroom, in the theological as well as in the secular space. How much more would these experiences, and their bodies, matter in moments of heightened social conflicts? Do we give credence to the growing chorus of detractors claiming that race should no longer be relevant as an issue in setting the social justice agenda of our day–because, how is racism possible in a post-racial society? As the body count of people of color grows, do we engage attempts to downplay the enduring legacy of racism head-on or do we reformulate our critiques to more palatable post-racial parlance?

Every educator of color, and those outside white-male heteronormativity, continuously deal with the ways in which our bodies interrupt the pedagogical space. Am I seen as capable enough? Should I be taken seriously? Did I say that only because I am a person of color? Do we have to talk about race, again? Our pedagogical practices are challenged to engage these times with a sharp mind, a zealous heart for justice, and an ongoing commitment to challenge structures of oppression and practices that devalue the lives of those at the margin of power. It is a struggle to challenge those worldviews that dehumanize and are continually bent to destroy the present and future of communities of color, while all along seeking to forget their past. In a society that proclaims the beginning of a post-racial era, a person’s race is still a determinant factor of whether a person lives or dies.

Every educator of color, and those outside white-male heteronormativity, continuously deal with the ways in which our bodies interrupt the pedagogical space. Am I seen as capable enough? Should I be taken seriously? Did I say that only because I am a person of color? Do we have to talk about race, again? Our pedagogical practices are challenged to engage these times with a sharp mind, a zealous heart for justice, and an ongoing commitment to challenge structures of oppression and practices that devalue the lives of those at the margin of power. It is a struggle to challenge those worldviews that dehumanize and are continually bent to destroy the present and future of communities of color, while all along seeking to forget their past. In a society that proclaims the beginning of a post-racial era, a person’s race is still a determinant factor of whether a person lives or dies.

Even with the increase of technology mediated interactions, a primary way in which students interact with their lead instructors is through their physical presence: the shape, color, and gender of their bodies and the ways in which they carry that body through the space of the classrooms; the speed with which they move, and how much of that space they use; the timber of their voice and how they inflect it to make a point or respond to a question; the pace of their speech and the use of silence in teachable moments. Bodies matter because, at a micro-level, they are manifestations in the rooms in which they are present, of macro-level webs of signification in which they exist. These bodies are imputed social meanings that set construed parameters of action, that shape how they are perceived and what they are supposed to do. Educators of color and those whose identities lie outside the white-male heterosexual construct, then face a task of working through the meanings that are imputed to their bodies and what those bodies are taken to represent. The power such representations have over the pedagogical space cannot be underestimated.

The second question that drives my reflections here is how such awareness shapes my pedagogical practices in teaching contexts in which bodies of color are not the norm. As an educator of color in a theological institution, I find myself continually engaged in considering the ways in which concerns for social justice influence my pedagogy in light of the ways my body signifies just by being there, by occupying the pedagogical space. In a nutshell, I was forced this summer to consider at a deeper level two of my driving pedagogical questions: “What are you about?” and “How do you become a worthy ancestor?” As a young man of color, and son of the Black diaspora in the Americas, I am deeply aware that my education, achievements, and current social status are not protection against the violence of a society that daily claims the lives of people of color. I could be in the classroom one night living out my vocation as an educator, and the next morning commentary on my broken body could be occupying the news.

The task of social justice pedagogy, and particularly the pedagogy of those of us engaged in critiquing racist practices, takes place in a time that contends the relevance of race. Ironically, these positions that herald the end of racism, take shape at a time that sees the continual erosion of hard fought civil rights gains for communities of color, such as affirmative action legislation, the ongoing political, educational, and economic disenfranchisement that curtails full flourishing of the present and future of Black and Brown communities due to incarceration, unemployment, and the crumbling safety net -- and of course, public neo-lynching spectacles of people of color by police force. How else could the beating to death of a Brown man be named, or the shooting and bleeding to death in the middle of a street, and in broad daylight, of a Black young man, For this reason, I challenge my students by asking them these questions too: to consider what their lives are about, what the legacy is that they will leave behind, and to come face-to-face with the expansiveness of our collective social justice vision that is bounded only by the audacity of our moral imagination. Whether we live up to that challenge is up to each one of us. But our decisions will contribute to the collective shape of the future. As a theological educator, I often wonder whether I teach what I do and teach how I do, not in order to satisfy a curricular goal, but in order to live – to foment the survival of the communities of color to which I belong. Although (as far as I know) my life has not recently been in immediate danger, in this society, any moment can be my final curtain call. In case of the latter possibility, others will have to answer the questions that drive my social justice pedagogy: What was I about? Did I carry myself in a worthy way following the path of my ancestors to join them?

Two weeks after the death of Mike Brown, families and friends of Omar Abrego, and community members decided to protest. They took courage in the opposition to brutality and their contentions acts to disrupt a system that for too long has treated the lives of people of color as disposable, and they sought justice for a loved one. En la lucha…

[1] See ATS folio, “Diversity in Theological Education,” http://www.ats.edu/uploads/resources/publications-presentations/documents/diversity-in-theological-education-folio.pdf

*Original blog published November 17, 2014

This piece is extraordinarily helpful. I identify with your reflections — particularly about the ways a theological educator’s body can interrupt pedagogical space. Thank you for giving attention to this phenomenon and highlighting the pedagogical role of embodiment.