Resources

Attending to the public pressure to rethink societal oppressions requires trustees, faculty, student and administrative alignment. Leaders taking risks for prophetic agendas is the work of justice in theological education. Do not be forced into silence! Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield hosts Dr. L. Serene Jones (Union Theological Seminary).

emilie m. townes Dean and E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of Womanist Ethics and Society Vanderbilt Divinity School The opening paragraph of the Vanderbilt University Statement of Commitments: The Divinity School is committed to the faith that brought the church into being, and it believes that one comes more authentically to grasp that faith by a critical and open examination of the Hebraic and Christian traditions. It understands this faith to have import for the common life of men and women in the world. Thus the school is committed to assisting its community in achieving a critical and.

What are the practices which might assist us as we endeavor to still ourselves to sustain the genuine? Who are the trusted people who we rely upon? What role does the body play in sustaining the sound of the genuine, the feeling of the genuine, the experience of the genuine?

The current rebellions and outrage is appropriate given the history of race politics in the USA. White scholars are called to use their curiosity, imagination and teaching competencies to embed into the curriculum anti-racist content, tactics, and strategies. Find ways not to let racial violence be overwhelming; practice deep listening, dialogue and community building with minoritized people. Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield hosts a conversation with Dr. Jan Love (Candler School of Theology - Emory University).

Who or what is God? Words can only say so much about who God is or what God isn’t. Thankfully our thinking isn’t limited to words. Through Art Theology -- using the creative languages of the arts -- we can form new ideas, questions, and perceptions about God. Let the words go and think in color. Thinking back to the very first ideas of God you ever had, what color comes to mind? Gray... Gray was the color of the beard of the old man in the sky, the first image I had of God the Father. Gray was the color of the clouds he sat on. In painting this first idea, I used cold, dark, black grays illustrating the vast remoteness of this idea of God. I began incorporating yellows and whites and softening places within the gray, creating warmth in the painting. As I did so I recalled my childhood struggle to comprehend how this cold, dark, mysterious God also made me and loved me unconditionally. [caption id="attachment_247214" align="alignnone" width="467"] The Cloud of Unknowing Angela L. Hummel 11x14 Acrylic on Wood[/caption] My concept of God changed when I was introduced to the idea of Jesus and the idea of God’s personal love. The gray remains but softens even more and I introduce an abstract brown line. God’s love expressed through Jesus felt so intimate and personal that I have at times a sense of knowing the nook of his neck, of having rested my head upon that shoulder line. Yet, I could not tell you what his eyes or nose look like. In some ways I do not know him at all. In other ways, that personal love of God is the most real thing in my experience. [caption id="attachment_247215" align="alignnone" width="390"] Personal Love Angela L. Hummel 11x14 Acrylic on Wood[/caption] Stepping back and looking at the first two paintings I felt a new question arising. I was physically uncomfortable as I reflected on how masculinely gendered my ideas of God had been. No matter what we think and understand theologically about God language, we carry these memories in our bodies. I felt myself reaching for new colors and lines: purples, blues, gold, and undulating lines. This next painting incorporates my reflections on Shekinah. Both women and men are made in the image of God. The divine feminine reveals a love that conceives, gestates, labors, births, nurtures, and sustains. [caption id="attachment_247216" align="alignnone" width="467"] Shekinah Angela L. Hummel 11x14 Acrylic on Wood[/caption] God is love. This love is mysterious, personal, intimate, boundaried, male, female, non-binary, fluid like water, beyond our comprehension. How can we reflect the love of God and learn to love in this dynamic way? Regardless of bodily function, all of us can learn to love more deeply by reflecting on how love conceives, gestates, labors, births, and sustains. The Christian focus on moral theology has led to judgmentalism that has caused some people to reject religion. Why don’t we devote as much attention to Christian love -- what this love is and how we live it? We need new ways of exploring this vast idea. We need Art Theology. Art Theology has helped me to move away from a monologic pedagogy into a dialogic way of teaching. When my students paint the colors and lines of their thinking about God they move into new ideas, questions, and dialogue that discursive reasoning alone could not take us into. The understandings that we have arrived at through this method have transformed my classroom into a dynamic place of collaboration where together we have learned to see God as truly other, for who God is, not constrained by our previous limited definitions and arguments. Angela L. Hummel

Dr. Willie James Jennings (Yale Divinity School) is this week’s guest on the Dialogue On Teaching podcast. Jennings and Dr. Nancy Lynne Westfield discuss his upcoming book, “After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging,” which will be published in October 2020.

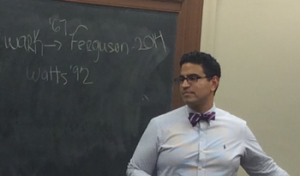

Elias Ortega-Aponte, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Afro-Latinos/a Religions and Cultural Studies Drew University As I geared up to teach two social justice themed courses this Fall, my summer preparations were disrupted by the news of two tragedies and the reflections they prompted. First was the death of Omar Abrego, beaten to death by police on August 2 in Los Angeles. Witness reports claim that Abrego was taken out of his car and beaten up by two police officers for at least 10 minutes, and left in a pool of blood. The father of three would die hours later in a

Travel Information for Participants Already Accepted into the WorkshopGround Transportation: About a week prior to your travel you will receive an email from Beth Reffett (reffettb@wabash.edu) with airport shuttle information. This email includes the cell phone number of your driver, where to meet, and fellow participants with arrival times. Please print off these instructions and carry them with you.