Searching for Zora: Auto/mobility and the religious imagination

None of the women in my motherline drove a car regularly before the 1970s. To get to where they were going next in their lives, when they left where they were born, they navigated saltwater roads. They moved house; whole villages, islands, and continents receding in their wake. They lived as the newly arrived outsiders in other Caribbean islands, the United States, England, and Canada as they gave birth to us, the next generation. Before she got on the boat that would cross the Atlantic to England, my mother walked her island world just up the road from the deep-water harbour.

None of the women in my motherline drove a car regularly before the 1970s. To get to where they were going next in their lives, when they left where they were born, they navigated saltwater roads. They moved house; whole villages, islands, and continents receding in their wake. They lived as the newly arrived outsiders in other Caribbean islands, the United States, England, and Canada as they gave birth to us, the next generation. Before she got on the boat that would cross the Atlantic to England, my mother walked her island world just up the road from the deep-water harbour.

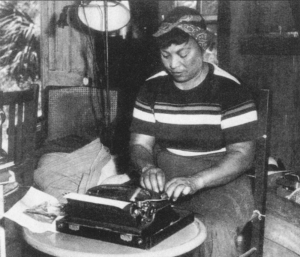

My work as a teacher, scholar, and writer focuses on the religious lives of everyday folk in communities in the African Diaspora in North America and the Caribbean. The oeuvre of anthropologist and writer Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) helped me hone some essential items in my toolkit. Key among these is Hurston’s recognition of the centrality of oral traditions in southern US black communities. Her brilliance as a scholar and writer is based on her keen observation as an anthropologist and on her self-reflexivity as a member of the communities with which she worked. Her stance was unusual for the 1930s and prescient of the call for research reflexivity in anthropological and other social sciences and humanities which emerged later in the twentieth century.

Hurston was also a traveler. She journeyed throughout the US South and the Caribbean including Haiti, the Bahamas, and Jamaica, to record the stories, songs, and folklore of black communities. She drove a car on her trips through the rural US south conducting research. In a memorable episode recounted in her 1942 autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road, Hurston tells readers about her escape from a conflictual situation in a work camp by leaving late at night and driving away.

She also wrote about a road trip and her drive across the Canada/US border from the state of Michigan into the city of Kitchener in southern Ontario. I was intrigued to learn that Zora Neale Hurston had driven through, or possibly even stayed, in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. I teach at a university in what is now called Kitchener-Waterloo. For years, I have tried to retrace her steps in the Kitchener end of town imagining where she may have stopped for a meal or an overnight stay. Did she park her car on Duke Street in downtown Kitchener close to where Canada’s first black lawyer, Jamaican-born Robert Sutherland (1830-1878), operated a law practice decades earlier? Did she stay at any of the inns or on the outskirts in nearby smaller towns? Perhaps she rested in a rented room with a black family using the informal word-of-mouth shared information which helped black travelers navigate racially segregated landscapes.

Hurston enigmatically notes in her observations that life on both sides of the border looked very similar from her vantage point. What did she mean exactly? I interpret Hurston’s comment as referring to social as well as geographical landscapes. It is a sly indication that de facto racial segregation existed across the border in 1930s Ontario. Racialized segregation shaped her experiences on both sides of the US and Canada border. Hurston’s strategies of navigation as a black woman driver and traveler would have been needed in both places. Indeed, the Canadian historical record supports Hurston’s assessment. After all, Herbert Green’s Green Book, a handbook for black motorists on road trips published from 1936 to 1966, provided references to safe places not only in the US, but also across the border in Canada, in the province of Ontario.

My search for Zora in the local and regional African diaspora is not only through textual and visual records but also literal as I walk the streets of small towns and drive rural roads in my very old car trying to match place names from old maps and memoirs with current locations. Sometimes I meet an empty field or a church building now repurposed as a home but on occasion I have visited buildings which are still standing and church communities which are vibrant even though their locations have shifted.

Surrounded by rural farmlands and smaller towns, Kitchener-Waterloo is located on the traditional unceded territory of the Haudensaunee, Anishnawbe, and Neutral Indigenous peoples. As a British-born black woman of Caribbean heritage living in Canada, I have thought about how my own complex identity has been shaped by forced and chosen migrations of previous generations. In courses that I have designed, I ask students to read, think, and write about the local in connection to regional, national, and international historical and contemporary contexts. In doing so, they are encouraged to consider studying religion and culture beyond static notions of historical dates and immobile structures and fixed figures. This approach challenges ideas of “history” and “religion” happening to abstract, far away actors while the current local context remains unexamined, safe, and uncomplicated.

Citations:

Hurston, Zora Neale. Dust Tracks on a Road. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991

Leave a Reply