Theology in Sound and Motion: Perichoresis, for Brass Quintet

John of Damascus, one of the most important theologians of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, writes the following about the relationship between the three Persons of the Trinity:

[They] dwell and are established firmly in one another. For they are inseparable and cannot part from one another, but keep to their separate courses within one another, without coalescing or mingling, but cleaving to each other. For the Son is in the Father and the Spirit: and the Spirit in the Father and the Son: and the Father in the Son and the Spirit, but there is no coalescence or commingling or confusion. And there is one and the same motion: for there is one impulse and one motion of the three subsistences, which is not to be observed in any created nature.

The Greek word “perichoresis” has come to refer not only to this multi-dimensional, incomprehensible unity, but to a particular metaphor describing this relationship: that of a “divine dance” between/among/within the Trinity.

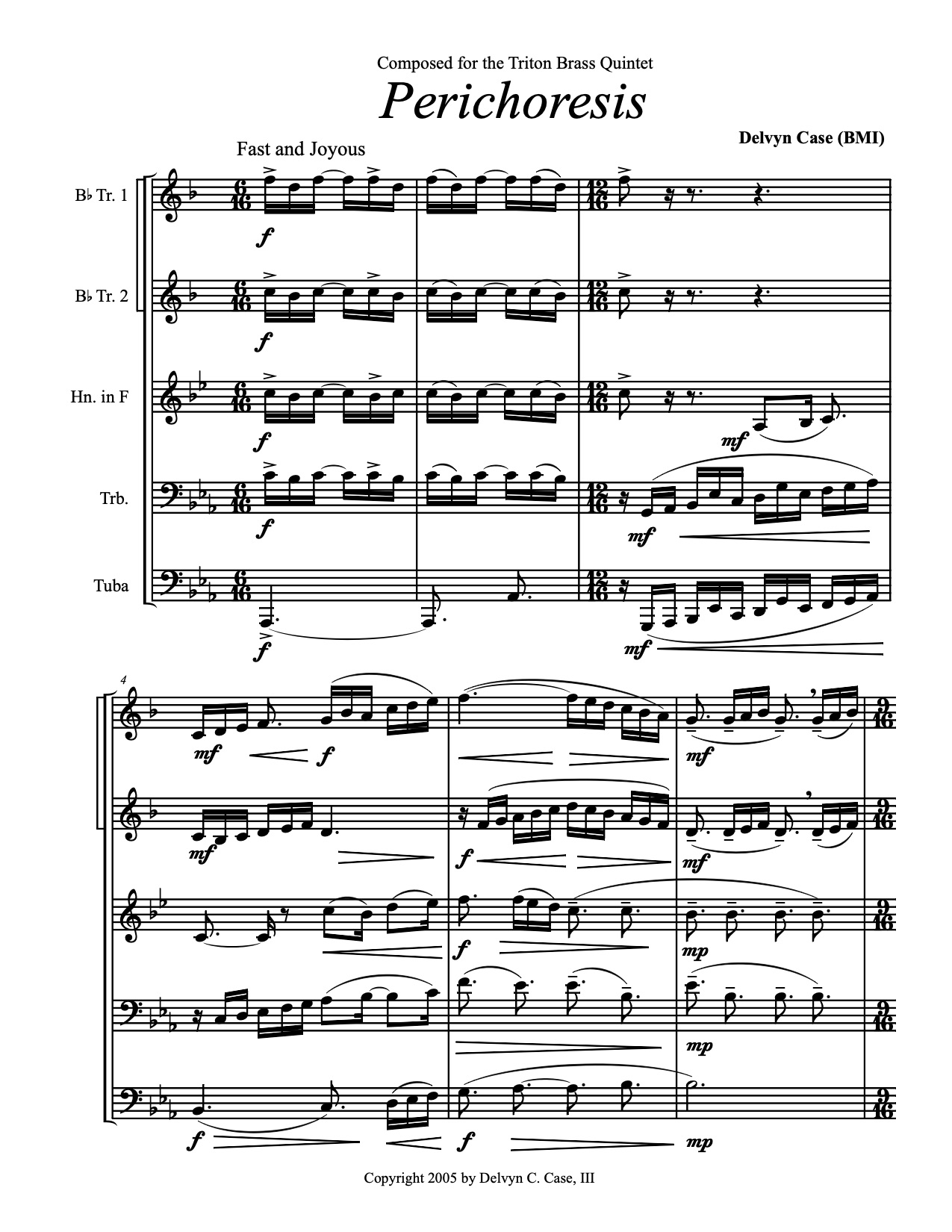

My composition Perichoresis[1] is my musical impression of this “divine dance.” Its overall mood is joyous, an ecstatic whirling-about in which all three members become lost in the ecstasy of divine fellowship. At the exact moment of the dance when one member moves, the other fills in the spot left vacant. Seen from afar, the effect might be like looking at a spinning wheel whose spokes disappear from view, yet which retains its speed, energy, and power. Musically, this occurs through the technique of giving each of the five instruments their own, equally important roles to play. In the fast sections there is no clear melody that dominates the texture, relegating the other parts to mere accompaniment. Instead, each musical “voice” contributes its own unique and independent strand, each often winding around the others in a musical version of indwelling. The complementary rhythms and melodies often make it difficult to distinguish these layers, yet the absence of any one of them would leave an obvious hole in the musical fabric.

Musical textures create a sonic example of an ideal community: one body, many parts, and none more important or unique than the other. Unlike visual art-forms, music brings to life these types of complex relationships in ways that make sense to us humans. Music allows us to hear individual parts at the same time as we hear the whole that they create. The bassline of a Beyoncé track is 100% funky without anything else. Yet, when part of a family of horn riffs, drum loops, background singers, and lead vocals, that constituent element takes on a new identity. It is the same as it was, yet completely different: a new thing, yet not new at all. Its beginning is its ending, its Alpha already its Omega.

Musical textures create a sonic example of an ideal community: one body, many parts, and none more important or unique than the other. Unlike visual art-forms, music brings to life these types of complex relationships in ways that make sense to us humans. Music allows us to hear individual parts at the same time as we hear the whole that they create. The bassline of a Beyoncé track is 100% funky without anything else. Yet, when part of a family of horn riffs, drum loops, background singers, and lead vocals, that constituent element takes on a new identity. It is the same as it was, yet completely different: a new thing, yet not new at all. Its beginning is its ending, its Alpha already its Omega.

The Trinity expands upon this idea by challenging us to imagine a mutual interpenetration of the parts and the whole.

As a teacher, a composer, and member of the Body of Christ, this is the model of community for which I strive. In the classroom or the rehearsal studio my goal is to create an environment in which my students and I take turns leading the “dance.” But this only happens when I get out of the way, when I recognize that my students are not small-scale versions of myself, but rather young people whose lived experiences are fertile sources of knowledge.

In the classroom, this happens when I allow a discussion to take on a life of its own, skipping down paths I didn’t even know were on the map. In orchestra rehearsals it happens when a French horn player’s phrasing opens up a new dimension of musical interpretation, changing the way I conduct an entire passage. In both situations, the requirement is that I stop trying to hear the content of my student’s ideas, and instead listen to the ways those ideas express their full humanity—when I listen through or beyond their words to understand who they are. When this happens, the space I vacate does not remain empty, but is immediately filled with a presence: a person whose life is both similar to mine and different, and with whom I can now collaborate as co-learner and co-teacher.

As in the classroom and the rehearsal hall, however, there are many moments in Perichoresis when certain parts come to the fore and others step back. In the slow middle section, a lyrical melody ebbs and flows, sometimes played by one instrument and sometimes joined by a partner. But even in these moments we don’t lose sight of our ideal vision of community. The melodies only sing because the ground beneath them allows them to stand. Conversely, the accompanying chords draw their notes from the melody, taking a line and turning it into an object: something solid and substantial. When I’m lecturing or leading discussion, I try to remember that I don’t need to be the melody. While my voice may be the most prominent at those moments, thinking of myself as the accompaniment is a way for me to recontextualize my role. My words can be the fertile soil for my students’ nascent ideas, the ground on which they can learn how to stand.

I don’t always get there. As a teacher, husband, father, or church member, I often find myself singing the melody before I’m even aware of it! As I learn how to undo years of uncritical acceptance of my importance as a white guy, it’s helpful for me to look to music as a model: it is, after all, the most evanescent of all artforms, a will-o’-the-wisp that disappears as quickly as we hear it. Its fundamental weakness, however, belies an extraordinary power: power that can change hearts and minds—but only if we allow it in, if we really listen to it.

My hope is that listening to my composition will help you think in new ways about the Trinity. Perhaps it will help you imagine how three Persons can be One, or One Person can be Three. And perhaps, the next time you listen to music, you might even be inspired to take it as a model for your life as a teacher, leader, or community member: a model based on relationships, mutual indwelling, and the joy of the dance.

[1] Composed by Delvyn Case, and premiered by Boston’s Triton Brass Quintet, Perichoresis has also been performed by the Grammy-winning Chestnut Brass Company. Of this piece, theologian Walter Brueggemann wrote, “I am not a great theologian but have pondered ‘perichoresis’ for a long time. This is the finest exposition of that thick idea that I have encountered.”

The audio is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GoHExKMJLk.

Leave a Reply