Resources

The Wabash Center teaches toward freedom in hopes of liberation and healing. We have learned that acts of freedom occur in many forms, and occasionally involve receiving permission. Since 2019, I have had the honor of reading the feedback forms completed by participants at the end of events and programming experiences. In addition to reading the feedback, there are regular occasions of extemporaneous comments from participants about the insights they have gained during the convened conversations. There is a reoccurring theme: the experience of having been given permission. They have reported having received permission to move towards new habits, practices, attitudes, approaches, and aspirations. Permission to strive for improved teaching is a key theme. Permission to expect more care, consideration and regard from the institutions by which our participants are employed is often mentioned.Much of this feedback comes from early-career colleagues for whom learning to navigate faculty culture is new. Similarly, there are a significant number of seasoned colleagues for whom the Wabash Center sponsored conversations are lifegiving and permission providing.I hear gratitude in this feedback. More importantly, I hear that the giving of permission has been moments of empowerment, agency, healing and inspiration toward freedom. I want to share with you a list of the kinds of permissions that are reported in hopes that you too might be encouraged towards new freedoms.Participants have said that, I received permission …….to develop my own voice, to speak up and speak out without embarrassment, fear, or guiltto take the authority given me by my role and responsibility through hire, tenure or promotionto think differently about the established traditions or about the outmoded presumptions of my institution or academic fieldto, rather than give my power away, make decisions that are faithful to my values and ethicsto command and adjust my own syllabus in my own coursesto act as a good citizen in my institution in ways that align with my own needs, wants, aspirations, desires and longing; to work in integrityto prioritize my mental or physical health and the wellbeing of my familyto teach across disciplines for the benefit of my students and in ways that meet their expressed curiositiesto strive for a work/life balance and maintain that balance over my careerto say “No” to requests which do not suit me or which would overload or overwhelm meto ask that I be called by the name of my choosing (with or without title) and that my name be correctly pronouncedto report acts of bullying and aggression against me or othersto seek counseling, coaching, mentoring, spiritual direction throughout my careerto take the time and needed psychic space to grieve over the failure of a significant achievement or the loss of a belovedto be creative, imaginative, and wonder as an approach to teachingto pursue outside interests, hobbies, and playto resist grind culture, to resist productivity at the expense of my own wellness or the wellness of my familyto communicate when acts of violence like racism, sexism, classism, homophobia occurto parse between the obligations of my scholar/teacher identity and my employment dutiesto rest.The list is in no way comprehensive or exhaustive. I give you the list so you can see the kinds of issues which need to be attended to so that a healthy work environment is created and maintained. It takes hard work to move from a toxic and unhealthy culture to a culture of care, belonging, and justice. Perhaps giving permission to individuals to make healthy communal choices is a start.

Steed V. Davidson Associate Professor of Old Testament Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and Church Divinity School of the Pacific Each night I watch Jeopardy. Occasionally I am thrilled when Tobago or Trinidad features in a clue. This thrill comes from knowing that the island where I grew up (area of 116 square miles) has found its way into the knowledge required of Jeopardy contestants. I take this small thrill, and I am painfully aware of how small it is, because for most of my life I have been told that the intellectual knowledge that matters consists of material outside of..

What excites me about teaching theology to the Z-generation is their unabated courage. Admittedly, their actions online and public voices could get them into some pickles at times, but they model for previous generations the need to be concerned about things that matter, eternal things that matter to God. Issues of social justice, accountability, transparency, solidarity, lasting peace, and equity are important to my students even if they do not share the same commitment to organized religion their parents do. Their fresh voices are critical, but they also need to be political, in the best sense of the word, to achieve results. When teaching a course on social justice, I encourage my students to reflect on three moves others have made to create social change. The first move is to study carefully the behaviors of ancestors who wished to communicate who God is and the divine plan. I invite students to study the prophets who call people back to the terms of the covenant. Prophetic voices direct people to see how their misery is a result of their deviation from the fundamental agreement between God and humanity. In fact, they are not only the inheritors of such horror, but in many instances, the perpetrators. Students recognize that they must be clear on how they understand justice and take responsibility for their own complicity in the evil of which they speak. None of the prophets seem quite comfortable in their vocation. Their calling displaced them from comfort to speak on God’s behalf. As they came to embody God’s vision, however, their voices became clear, emboldened, and confident. Once students realize that their call to rectify injustice is part of an eternal effort, their voices are are similarly strengthened. Next, I turn to the life of Jesus. Whether a student is a believer is not my concern. It is about examining Jesus’ movements to invite people to inhabit the vision and values of the basileia ton ouranon. Four dimensions of Jesus’ ministry strike me as examples of effective preaching. First, Jesus used vivid imagery to illustrate what God’s justice demanded. These stories invited listeners into a process that captured their imaginations and hearts. Second, like the prophets, Jesus was unafraid to eat with his opponents and call out the leaders of his people and identify how they had strayed from their responsibilities. Third, Jesus made time to recharge through prayer and intimate relationships. Finally, Jesus was an individual of integrity. His actions supported his words. Students generally appreciate the need to communicate data and share narratives. They waiver on engaging their adversaries, taking time for themselves, and being models of authenticity. The third move I point to is that of the prophetic missionary activity of Paul of Tarsus. In Paul’s efforts to evangelize the world with the Christian message, Paul tackles the hardest reality first: he engages the Jewish community and invites them to conversion before moving onto the Gentiles. What Paul models for my students is a political maneuver that is generally not appealing. They are accustomed to building a support network primarily through crowdsourcing, but Paul’s life and mission encourages to make their cases for social justice by going first to their staunchest detractors. This strategy of Paul’s is particularly troubling to my students. Why would someone with a vision contrary to the status quo engage opponents? When I hear this question, I remind myself that this is the generation that spends a lot of time and energy proposing their viewpoints online. Information communication technology becomes a platform then for them to enjoy supports or “likes.” Their preference for social media allows them to restrict who they follow and who follows them; ultimately their worlds become echo chambers. They hear me, but I am not sure they fully understand. Students are a sign of hope in our very troubled and uncertain world. In their nascent knowledge and youthful energy, they are eager to change the world. Unfortunately, they do not always recognize how complicated it can be. Many give up. Yet, the prophets, Jesus, and Paul all can provide models of effective engagement and hopeful transformation of the culture.

Is the study of theology worth it? That’s a question you and I might pose to our students at the beginning of every semester. At times, we may have to answer this query for ourselves. At the beginning of each semester, I presume this is a question that students have, particularly because at my university students are required to take three theology courses. The first day of theology classes, then, I offer a value proposition. (Now, mind you, I generally teach moral theology classes primarily to business and pharmacy students.) I tell my students that this course may not position them for their ideal job in a corporation or biomedicine, but that a theology course can help students think, write, and speak with a depth and breadth they before had not known. The subsequent question every term is, “but how will that help me advance in my career?” These developed skills, I tell them, will aid them in living out the challenging and, perhaps, painful realities of life. That has never been truer than in these days of Covid-19. One of the first topics I teach is “narrative.” I invite my students to consider what the foundational stories for different religions are. Conversations extend from the metanarratives that undergird traditional monotheistic religions to Rastafarianism, Wicca, and Mormonism. These class days tend to be lively ones as we move into discussions of the Branch Davidians and the Westboro Baptist Church. Good narratives mature over time as profound experiences impact and challenge them. My parents’ generation had Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the Second Vatican Council, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the rise of Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Honestly, it made me jealous. I wanted stories to add to my collection, but could not imagine having any of such historical impact as they had. How young and naïve I was! GenXers and I have experienced stories that have forced us too to reevaluate the foundational narratives in which we were grounded. The students in front of me, now on my computer screen, were curious about my generation’s stories. Mind you, when I first started teaching, as I suspect all of us are/were, we are/were our students’ older sibling. Now, I could be their parents and for that reason, they are curious. When asked, I speak of how marginalized groups and their allies consistently have fought for equality, particularly LGBTQIA+ citizens, communities of color, and immigrants; seemingly endless wars in Viet Nam, the Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq; governments, including the United States, having a wide range political scandals; 9/11; and, of course, the information technology revolution. For some reason or another, they are fascinated, and I suspect hungry like I was when I was younger to have their own stories. While some have alluded to the global digital transformation in their lives, there has never been a clear consensus as to what might unite GenZers in a common narrative. Now, there is. They get it. Students recognize that they must understand the profound effect this global health crisis has had on them, and on their narrative. For those who have been grounded in an understanding of who and what God is for them, they will have additional work that may take them places about they least expected to go. What will be required is what the study of theology provides: some deep thinking, critical writing, and clarity in speaking.

I teach biblical/theological studies. Each semester, I seek to guide students toward a deeper understanding of my conclusions concerning the major theological points of the Old Testament. I teach them that, as a result of sin, the world in which we live is not the world as God created it to be. The world is “broken.” However, the amazing story of the Old Testament shows us that God, despite the sinfulness of humanity, is making a way for humanity to be reconciled to him. The brokenness of this world is the primary reason we find difficulty present in our lives on such a regular basis. The story of the Old Testament teaches us that God uses these various kinds of difficulties to command humanity’s attention so that they turn their hearts toward him in dependence. My desire as a professor of the Old Testament is to find real connections to my students’ lives so that the Old Testament is not viewed as merely an ancient book, which has no real value to their contemporary world. And every semester, it is a battle because most of them are simply not old enough, nor do they have the life experiences that are sufficient enough, to lead them to more deeply understand the powerful truths of the Old Testament. Outside of the minor irritations of life, the majority of the freshmen or sophomore students in my courses lack that which would lead them to truly understand the theological points I am trying to make and, therefore, they can lack an interest in making the necessary connections. They still feel a little invincible and at the top of their game. Enter our global pandemic. I could not ask for a better “soft ball” to be thrown at me. It is a perfect scenario for the teachings of the Old Testament to come alive. This global pandemic has created the opportunity to openly discuss the issues confronting our world, and even the issues that confront my students, with the goal of connecting all of it to the profound theology of the Old Testament. Every situation this global pandemic brings into their lives becomes a special opportunity for them to understand the deeper realities of living in this world as we know it and all of its subsequent difficulties. Even if it does not touch their own lives in meaningful ways, they are bombarded with constant news updating them on the tragedies that other people in this world are up against. They feel it. And they are moved by it. As numerous emotional stories flow through various information platforms, it has an impact on them, making them more prepared to listen . . . and to think. So, my responsibility as a professor is to take full advantage of a crisis that I could not have planned. For my teaching, it is truly the “perfect storm” for the application of my course content. With the emergence of this global pandemic, my class is more interested in engaging the focus of my teaching. And they will be the better for it. Of course, this causes me to reflect on what might be less obvious in the everyday events of our world, which, if properly utilized, could create the same opportunity for my students to impacted. Perhaps, as a teacher, I have grown somewhat lazy in my attempts to connect the dots for my students. This has led me to think more deeply about the way I approach my course lectures. Consider the many issues that potentially confront my students on a daily basis: • At a private Christian liberal arts university, costing around $40,000 per year, this may not be an issue for my students, but one cannot help but be aware of the persons who have made a bus stop their home or walk down the street pushing their shopping cart full of their life’s possessions or who scrounge around restaurant trash cans in search of food. • Sex or human trafficking. It is difficult to believe that either sex or human trafficking could be happening in our neighbor’s home across the street or in an apartment complex in close proximity to our home, but it is possible. These “invisible” people may be closer than we think. It is a horrible issue in our world, and we can put it out of our minds. • Drug/alcohol abuse. More people will die of drug abuse in the USA than will die of this global pandemic in the year 2020. Drug abuse wrecks families, tears apart marriages, and leads to financial ruin. Students have more than likely seen the impact of this issue in one way or another. My point is that, although these issues may not directly impact my students’ lives, the global pandemic might not either. But, unlike the global pandemic, these other issues exist continuously in the world which my students and I inhabit. Oftentimes, these issues become background noise to our comfortable little worlds, but they are there. My job as a teacher is to work harder to make these connecting points when my students might be having difficulty making connection on their own. Because of this, I am thankful for the global pandemic. I know that my subject matter, the theology of the Old Testament, made it fairly easy for me to make the connections between course content and this global pandemic, but I assume that, with a little bit of thinking, you can do the same. And, if you do, it will make your course content come alive and your students will be better able to draw value from the content of your course. And, if we can do it with a global pandemic, then I bet we can do it better in the situations of everyday life. I encourage you to go for it!

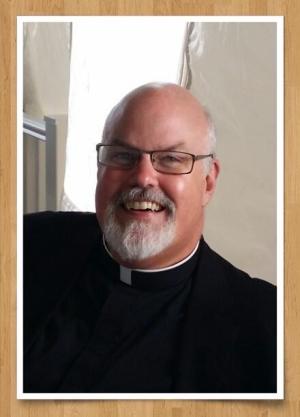

Teaching theology in the seminary is challenging. Many students, burning with zeal to do the “real work” of ordained ministry, pastoral care, often cannot immediately perceive theology’s role in that endeavor. Its utility for building community, performing diaconal service, celebrating liturgies, or providing spiritual formation is often not as apparent to them as it is to us. I have found that one way to defuse students’ skepticism toward theology is by early, direct, and repeated emphasis on the relationship between theological imagination and the embodied practice of faith. Once students catch a glimpse of how theological symbols function (thank you, Elizabeth Johnson!) and, conversely, how practices shape theological symbols, they more readily apprehend how preaching, teaching, and living good theology are essential to providing the pastoral care they expect seminary will train them to give. Last July, I participated in the Wabash Center’s Teaching with Digital Media workshop for the express purpose of developing more tools to help students connect the study of theology to the practice of ministry. As part of an exercise during the workshop, I reconceived a paper assignment at the end of the first term of a two-semester introduction to theology sequence I teach annually. I turned it into an outward-facing digital theology project. Having students dip their toes into doing a bit of public theology as the culminating task of a semester of study designed to demonstrate the link between conceptual and practical theologies seemed like it would further my pedagogical goals. The assignment I gave them was to imagine themselves the director of adult formation at a church and to create an original meme (a still image or a GIF) for the formation-program Facebook page of the church. The meme was to communicate the importance of preserving a robust concept of sin in Christian theology and practice. Students had to share the meme as broadly as possible and solicit feedback on it. They then needed to write a brief paper that would (1) explain, in conversation with the relevant course texts, the theological choices made in creating the meme, and (2) report and reflect on how the meme was received and what the student learned from this as a theologian. The results were remarkable. [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="511"] Used courtesy of Nora Boerner, CDSP M.Div. student[/caption] Students created memes that were sometimes provocative, sometimes humorous, sometimes both. The richest and most sophisticated of them, not surprisingly, were produced by the students whose theological rationales were the most nuanced. What was gratifying about this was that they themselves realized this connection. They were able to grasp how easy it is to communicate theology sloppily and saw that providing a message consonant with the Good News requires a deep understanding of what that central communication is. If one is going to distill the Gospel into capsule form, such as a meme, with as little distortion as possible, solid theology is required. In cases in which viewers received a message different from the intent, students benefitted from a first-hand education in how easy it is to be misunderstood when concepts are not handled with sufficient care, and they could appreciate that this can have unintended negative effects on one’s audience and thus impair the pastoral relationship. [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="451"] Used courtesy of Sunshine Dulnuan, CDSP MTS student[/caption] Some students were made anxious by the assignment because of lack of familiarity with meme culture or trepidation over engaging in public theological commentary. Confronting both of these anxieties is important for church leaders in training. Effective public communication in the visual and syntactical languages various publics use is crucial for those charged with mission, discipleship, and evangelism (the three foci of Church Divinity School of the Pacific’s program of formation). This may mean learning idioms quite different from one’s default mode of communication, and needing to translate theology well from one into the other. The anxiety this assignment provoked was, to my mind, the one commonly experienced when confronting a developmental challenge, and so it was, in the end, a productive anxiety. [caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="405"] Used courtesy of Joanna Benskin, CDSP M.Div. student[/caption] This media-based assignment contributed nicely to my overall pedagogical objectives. Students were required to produce and disseminate a micro-theology expressive of their developing theological imaginations. They communicated a formational message with a theological foundation they could articulate and justify. They were thus given an opportunity to enter intellectually and affectively (and also tentatively and gently) into the arena of public theological exchange and to grasp how challenging, indispensable, and even, yes, pastoral, the discipline of theology can—and, in the context of these students’ particular vocations, must—be.

Perhaps one of the most painful memories I have of my early years in teaching was election night 2004. The pain comes from my too late realization that in my advocacy for a progressive outcome for the election I had semi-wittingly politicized my classroom in a way that still haunts me. I’d like to reflect for a bit on what happened and what I learned. What happened was quite simple. I was a progressive who was against the war in Iraq and the convulsions caused to our common life by extraction of our common wealth to finance massive tax cuts. Put simply, I was ardently against Bush and made no secret of it. In the weeks leading up to the election and the evening of the it, on which I had a class meeting, my advocacy had had the effect of drawing a political line along which members of the class sorted themselves. A consequence was that for the few weeks remaining after the election my pedagogical space consisted of political partisans and not a community of learners. What I learned from that was three-fold with the full effect being felt in the recent election. The first thing I learned was that I had spent insufficient time or energy teaching about my values, what they meant for how I understood the faith, and thus, how I constructed the task of teaching theology. Here I don’t mean to imply that I understand my role as being teaching my theology. Rather I want to suggest that it is good to realize that our values are being taught whether we are explicit about it or not. Being explicit means that I can reflectively engage students and materials in ways that shape our common experience. By focusing on values I can invite more people into our space than if it is a matter of politics. I did not do this work. The second learning was that I had spent insufficient time clarifying how I integrated scripture, faith, values in the work of theology for myself. So, while I am sure that I demonstrated a sort of integrity for my students it was not sufficiently reflective to build my teaching around. Certainly, the project to which I am dedicated as a theologian was/is clear and finds expression through my teaching but, at least at that point, the integrity at the center of teaching and that project were not clear. From this learning I changed my pedagogy radically. Teaching theology and not about it became my guiding pedagogical principle. The upshot of this change was that questions of the integration of scripture, faith, and values as the work of theology were at the center of every course from its beginnings. In the two classes I taught following the recent election I began with an observation that we as Christian theologians were being called into the public square at this moment for several very specific reasons. First, the candidate who won had made very specific promises about bringing harm to the weakest and most vulnerable among us, our neighbors. By placing promises to register our Muslim neighbors, round up and deport the stranger among us (immigrants), and the imposition of what amounts to martial law (a national stop and frisk policy), at its center the Trump campaign made the political theological. It is just here that my learnings of the past few years made it possible for our class(es) to grapple with our responsibility in this moment in ways that did not immediately devolve into partisan positions. We were able to draw on scripture, the various theologians we read, and our experiences of faith to imagine how to move forward. This was quite a bit different than in 2004. This then was my third lesson. By making the ongoing thread running throughout each class the explicit integration of our faith and values, it was then possible to interpret the political moment as a matter of faith and not partisan politics. A student summed up well what we had discovered on our journey: “loving and protecting our neighbor is a type of politics.”

Miguel A. De La Torre, Ph.D. Professor of Social Ethics and Latino/a Studies Iliff School of Theology While teaching at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa, I was traveling with a local colleague to an engagement. Along the way, I ribbed him concerning some native cultural idiosyncrasy; at which point he turned to me in jest calling me “just another imperial gringo.” Although a humorous retort in our banter, I confess that I was taken aback. Of all the things I have been called throughout my life, this was the very first time I was ever called a gringo.... Read

Lea F. Schweitz, Associate Professor of Systematic Theology/Religion and Science, Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago As a teacher, whenever I utter the words, “Okay class, please get into your small working groups,” I remember the sense of dread that...

Kwok Pui-lan, William F. Cole Professor of Christian Theology and Spirituality at the Episcopal Divinity School What if you were to stage a debate on the black Christ, instead of giving a lecture on James Cone’s black theology? If you...