Resources

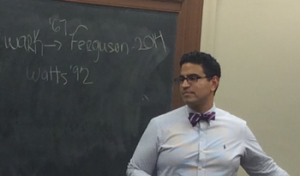

Elias Ortega-Aponte, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Afro-Latinos/a Religions and Cultural Studies Drew University As I geared up to teach two social justice themed courses this Fall, my summer preparations were disrupted by the news of two tragedies and the reflections they prompted. First was the death of Omar Abrego, beaten to death by police on August 2 in Los Angeles. Witness reports claim that Abrego was taken out of his car and beaten up by two police officers for at least 10 minutes, and left in a pool of blood. The father of three would die hours later in a

In a seminary setting with a daily rule of prayer, students and professors can easily fall into a trap of distinguishing between teaching students how to advocate for justice in the “real world” and the “in-church” liturgy of prayer and worship of seminary life. At times, the liturgical rhythms might even appear to be an intellectual or temporal straitjacket: hindering the work of classroom learning or service to the community and work for justice. However, in my own experience teaching in both Roman Catholic and Episcopal/Anglican seminaries, where the traditional Christian liturgy of the hours determines the structures and rhythms of the students’ lives and learning, I have found that teaching social justice in synergy rather than opposition to the liturgical tide has provided opportunity for teaching social justice rather than a hinderance. In fact, this immersion in the liturgy can transform teaching social justice into an act of recollection and connection building, rather than creating an oppositional dynamic. This “calling to mind” in beginning to teach social justice which immersion in liturgy permits has two crucial components. First, the daily liturgy of the Roman Catholic and Anglican tradition provides substantial content for beginning to discuss and understand the need for social justice and its objects. While there are calls to pursue justice throughout the scripture, the liturgy of the hours or of Morning and Evening Prayer, creates a special focus on the book of Psalms. In these liturgies, students will generally read in unison throughout the entire book every month, and then turn around and do it again. This means that students begin and end almost every day with the cries to instantiate God’s justice which fill the Psalms in their mouths and in their minds. Beginning a pedagogical engagement with social justice in the Christian tradition therefore begins with an acknowledgement of the Word which is already in their mouth, and then broadens to seeking to understand that word in the context of the present day. This grounding of the classroom discussion of social justice in the liturgy is, of course, far from novel, but stretches back through the Christian tradition. Explaining this tradition and explicitly linking it to their own immersion liturgy then prepares students for the task of analogical translation into their own world, of the ways in which Christians, from John Chrysostom through abolitionists to the Oxford Movement to Oscar Romero, have seen the liturgy as the point of departure out into the world to seek justice and serve the poor. Just as important as starting a discussion on what God’s justice might demand of them is helping them understand how their formation in the liturgy has better prepared them to work for social justice in the world. By its very nature, formation in liturgical worship demolishes the temptation to autonomy and the urge to seek the spotlight, and rather trains students to be communal, listen to others, and be patient with the small steps and slowly developing processes. For example, when students are taught how to chant the Psalms in choir, they learn that the goal is never to declaim, to take up the most space, to push their own voices forward. Rather, they are taught to listen to the tones and pitches of others, to join in the one communal sound, and to use their breath to sustain rather than project. In another example, students come to realize that the liturgy is only made possible by the invisible labor of the sacristans, who ensure that everything needed for the Eucharist celebration is clean, prepared, and its place, but who are never at the front or receive praise or applause. This approach is the exact opposite of what Martin Luther King, Jr. referred to in a famous homily a few months before his death as the “drum major instinct”: the urge to assume that you are better than other people because you are out in front and people notice you first (https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/drum-major-instinct-sermon-delivered-ebenezer-baptist-church). Rather than surrendering to this instinct, King urged his listeners to walk in the steps of Jesus Christ, who disdained the drum major position in order to be faithful in the unacknowledged work of bringing about God’s justice in the world: feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and visiting those in prison, rather than focusing on their own success or prominence in the eyes of those around them. Oriented properly, students formed in the liturgy have already developed the virtues and praxis which make this type of service which Dr. King describes possible. They are ready to pursue the slow work of justice, neither demanding the spotlight nor seeking to drown out fellow laborers with their own voices or opinions. Rather, they are already equipped for service, and the task of the teacher simply becomes how best to show them the way. *Blog Originally published October 21, 2020

I have been a consultant for the Wabash Center for more than a decade now, and I still often wonder what I am supposed to be doing when I consult, and how I should be doing it. Supporting colleagues in the intimate and courageous act of opening up their teaching to other colleagues’ input is often an uncharted journey. I think it’s even more challenging in an era where the primary pandemic I worry about is the one having to do with discerning what is true and real, and what is not. I think you can talk about this in any number of ways—COVID-19, racial injustice, climate catastrophe—but at heart the question is how we navigate the complex and multiple realities we and our students are inhabiting. I have had the enormous privilege of walking alongside two gifted colleagues these past few months—Dr. Mitzi Smith and Dr. Dan Ulrich—as they took on the challenges of designing and leading a course together, where one of them was the expert and the other was the learner, all the while walking alongside their student learners. Drs. Smith and Ulrich are Second/New Testament scholars, teaching in two very different seminary contexts. Dr. Smith is an African American woman, and Dr. Ulrich is a white man. This last sentence is at the heart of the project they took on, within the Wabash Center’s grant program, to imagine and embody what it can mean to develop a pedagogically effective and ethically responsible trans‐contextual online intensive course. They set out to bring into focus African American and womanist approaches to sacred texts—both those of the Bible, and those of the lives of women and men whose struggles are part and parcel of having no permanent shelter. Dr. Smith was the formal teacher, Dr. Ulrich the formal learner. And I was a listener, a learner, and perhaps a cheerleader as they tried to walk this walk. I think I know a lot when it comes to designing learning in digital spaces—but much of what I know is not relevant when trauma is the essential ecology in which we are living. Here are things I learned: Teaching and learning are thoroughly relational, and this moment in time requires us to face that reality directly and intentionally—it is no longer possible to pretend that what we do is purely cognitive. It’s really difficult to be trained as an expert in your discipline, and from that training demonstrate being an active learner. Humility and openness are key to navigating this terrain, but they are rarely the skills or capacities we are rewarded for in our scholarship. Empathy, not sympathy, is essential in this work but the difference between these two abilities is not generally taught in higher education. Certainly our students find the distinctions very difficult to parse. Structural and systemic racism are so much a part of higher education that it takes a lot of effort simply to discern the “next right step” in resisting them. Teaching together needs to begin in relationship-building long before a syllabus is written, let alone implemented. There is a necessary balance to be found between the improvisational nature of teaching when you are doing it alone, and the shared work of collaborative pedagogical design. Institutional constraints will force certain problematic compromises to be made no matter how committed you are to justice. Here are questions I still have: What kind of authority is it necessary to have in a class? With a colleague? As a consultant? How do you say “I’m sorry” in a way that matters? What does it mean to be an “expert” in an academy so riddled with injustice that the very performance of “expertise” may be re-inscribing that injustice? What degree of transparency is important for students gaining a sense of the power dynamics embedded in specific academic disciplines, and when might it be better to obscure them? I am left with a profound gratitude that there are scholars in this world who are seeking to break down some of the power dynamics of the academy. I remain thoroughly committed to the search for a “pedagogically effective and ethically responsible trans‐contextual” way of teaching even if I’m still not sure what that looks like—at least this project has offered me a hopeful glimpse!

Character formation plays a crucial role in enabling students to engage effectively in endeavors related to social justice and civic engagement. I have wrestled for a long time with how best to help students respond to societal challenges such as inequity, prejudice, and discrimination that they face or observe. As an ordained clergy of the Wesleyan Church, I fully embrace my denomination’s rich tradition of social justice. In addition, I seek to live out the belief that humanity can experience deep spiritual transformation that leads one to embody Christlikeness. I integrated these concepts in my teaching very early on in my career. However, I became even more acutely aware of the centrality of character formation to my teaching when I joined the faculty at Indiana Wesleyan University. The University’s mission statement reads, “Indiana Wesleyan University is a Christ-centered academic community committed to changing the world by developing students in character, scholarship, and leadership.” Every semester, I would teach one or two sections of the BIL102—New Testament Survey course as part of the General Education core. One of the purposes of the GenEd core is to help students begin to embrace Indiana Wesleyan’s World Changing mission. In the course in question, I design the learning in alignment with the purpose “to develop and articulate a Christian way of life and learning that enables virtue, servant leadership, and citizenship in God’s Kingdom.” Since every student has to take BIL102, I relish the opportunity to have students from different backgrounds engage the biblical text. During the class, I am intentional about challenging students not only to engage the text but also to encounter the person about whom the text speaks: namely Jesus. In our reading of the Gospel of Mark, I focus particularly on Jesus’s encounters with the marginalized. I use narrative techniques to help students place themselves in the shoes of different characters, and challenge them to wrestle with the implications of reading the text from different vantage points. More particularly, I ask them to name an aspect of Jesus’s identity and character that they can emulate. I remember the day a student described Jesus as “sassy.” I was shocked! I am not a native English speaker. The definition of “sassy” that I learned—rude, impertinent—did not match what I knew of Jesus, nor what I hoped my students would want to emulate. Thankfully, I managed to not voice my initial reaction, “How did you get that from the text?!”, but instead replied, “Tell me more!” The student went on to describe Jesus’s direct and, in her words, “no-nonsense” posture toward people. The student used Jesus’ interaction with the Syrophoenician woman in Mark 7 as a case in point. I conceded to the student that Jesus’s words seemed harsh, and I allowed the class to enter and dwell in the awkwardness and difficulties of the narrative. In the end, I was successful in encouraging the student to think of a different way of describing Jesus. My success was short lived. As we journeyed through the Gospel of John, the student became even more convinced of Jesus’s sassiness. I realized that it was necessary for me to pause and grasp the way the student understood the word, and what they were seeing in Jesus’s interactions with people. It dawned on me that Sassy Jesus was appealing because of the balance of truth telling and deep compassion that he displayed. While I struggled initially with the concept, Sassy Jesus eventually became part of the New Testament Survey experience. As I helped students prepare for a lifelong commitment to service and engagement as world changers, the idea of being bold and courageous in telling the truth while showing deep love and compassion began to take root. They found Sassy Jesus to be a relatable person. They found it less difficult to emulate and embody the requisite balance to speak the truth in love. To participate effectively in endeavors surrounding social justice and civic engagement, students need to be resilient and compassionate. It has become more and more difficulty to maintain this balance in public and private life. On the one hand, people hesitate to challenge or call out another person for fear of being viewed as intolerant. On the other hand, there is a tendency to confuse love and compassion with conformity and/or compromise. Jesus mastered the art of welcoming and going to people with whom he disagreed, people who were outcasts, and even people who thought they had everything figured out. He knew how to show them unconditional love and how to challenge them to embrace a better way of life, the way of the Kingdom. One of the greatest challenges we face as educators is to help re-create environments where students not only learn the skills but also develop the character necessary to engage in irenic conversation about difficult issues. We need to design learning opportunities that produce growth and maturity that lead to boldness. We need to construct experiential learning opportunities that build empathy in our students. This will enable them to stand against injustice, prejudice, and discrimination. It will empower them challenge others with the boldness and compassion that come from emulating and embodying the character of Sassy Jesus.

The social justice issue that I have consistently raised in my biblical exegesis courses has been US immigration. As I tell my students—mostly white middle-class Protestants fixed on parish ministry—engaging this topic in a sermon will likely incite some criticism from parishioners or even set in motion a premature resignation. Despite my school’s borderlands location and the exilic content of the Hebrew Bible, pivoting to the topic of US immigration in a biblical exegesis course cannot be done haphazardly. In terms of texts, I find that Genesis (12–50), Exodus, Psalms 120–134, Second Isaiah (40–55) and Lamentations are especially apt for engaging this complex sociopolitical topic. What is unavoidable in these texts are stories about people on the move because of famine, jealousy, conquest, or faith—to name just a few. Yet still, connecting these biblical stories to the lived experiences of migrants in places like the US-Mexico border is by no means a linear process. No matter how convinced I am that Abram’s journey from the Ur of the Chaldeans to the land of Canaan (Gen 11:31) is a migration story, in order to bring my students along I must confront the assumptions that inform their understanding of migration. A common assumption they often have about migration and by extension immigration is that both phenomena represent a social problem or challenge. At the source of this assumption is indeed not an ancient notion of migration but rather their nation-state formation. By contextualizing the latter, students discover that the problems most associated with migration and immigration in US dominant society—like border crossers as “illegal,” economic strains, cultural threats, and spreaders of disease—stem from Western nationalist forms of inclusion and exclusion. After discovering their own nation-state biases about immigrants, I find it easier to shift to the theme of migration in the biblical text, contrasting along the way the ancient assumptions that likely informed it. As opposed to nationalist thinking, the biblical text often starts with the assumption that humans are free to move and that this movement constitutes an act of faith rather than a crime. Emphasizing the freedom of movement and the faith that accompanies it in the biblical text, I then pivot to US immigration and the sociopolitical injustices produced by the nation-state’s control of human mobility. Though migration studies, forced migration studies, and refugee studies are useful resources, their approach to immigration is often based entirely on the modern concept of the nation-state and hence tend to view borders, citizenship, and state sovereignty not as human constructs but as natural to our earthly existence. This nationalist-centric agenda can also be transferred unwittingly over to the biblical commentary material that relies on the social sciences. For this reason, I supplement my immigration bibliography with migrant artwork (See https://artedelagrimas.org/), particularly the kind that emphasizes the freedom of movement and faith as in the drawing below: Dayana, “Mi Jornada (My Journey),” colored pencil and marker, 2014, 9 x 12, Arte de Lágrimas Gallery. Dayana is from Guatemala and was 7-years old when she drew this art piece about her asylum-seeking journey to the US. She and her mother travelled by car and then by bus. She remembered that the road was long and gray (left side). Her picture narrative ends with them crossing the Rio Grande on a makeshift raft (lancha). She first drew the rocks (piedras) in the river and then the river banks. Next, she drew the makeshift raft in the middle of the river with her and her mother inside it. I asked, “Did anyone say good bye to you?” She replied, “My aunt.” She placed her aunt on the Mexican side of the river waving goodbye. I then asked, “Was there anyone else?” Not saying anything, she removed the rosary from around her neck and traced the plastic crucifix over the Rio Grande. She then began to sing the hymn “En la Cruz, en la Cruz, yo primero vi la luz, y las manchas de mi alma yo lavé, fue allí por fe yo vi a Jesús, y siempre feliz con El seré (At the Cross).” Her and her mother sang these words while on the raft. In the drawing the cross is the symbol of faith that accompanied Dayana’s migratory movement across the Rio Grande—the symbol of a territorially bounded state. Like Abram’s story, her faith assumes the freedom of movement.

For many years I have been involved with a team of instructors teaching a required first-year formation class at the Iliff School of Theology. Initially called “Identity, Power, and Difference,” we designed this class to invite students to reckon with the realities of structural inequality and oppression in relation to their vocational paths. Our goal was to increase student commitment and capability for seeking justice as a core part of their religious leadership in multiple contexts. Additionally, the course was designed to allow students the space to begin to wrestle with the emotional and personal implications of these systemic issues before they encountered them in classes in Christian history, theology, ethics, sacred texts, and practical theology. In those courses, they would need to work with these issues in more complex academic ways, and not become overwhelmed or resistant because of fragility or novice learner status. This is particularly important for students whose identities often place them on the upper side of hierarchies of privilege and oppression and who were not practiced in understanding and navigating such realities. One of the commitments early on was to attempt to work intersectionally, rather than learning about oppression identity category by identity category. We didn’t want to begin working with racism, then sexism, heterosexism, classism, and maybe have time in a ten-week quarter to get to oppression rooted in ability, religion, nation of origin, age, etc. We wanted to avoid setting up the idea that these are competing categories demanding attention and redress. Many helpful resources (such as the Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice textbook edited by Maurianne Adams and Lee Ann Bell) take precisely this approach, providing materials that focus on one area of identity-based oppression at a time. There is a clarity of focus on each particular form of oppression in this approach. However, the realities of intersectionality, first articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, mean that doing so often makes invisible the experiences of those who reckon with multiple forms of intersecting oppression. It also obscures the ways that a single person may have a complex identity matrix that includes both targeted and dominant elements (gay white men or straight women of color, for example). The concern is that imagining that these forms of oppression work independently from one another, or that they do not develop together historically or inflect one another constantly, sets students up to focus on one aspect and fail to recognize complex social dynamics in which their work occurs and the shifting ways their embodiment is interpreted by those around them. Of course, all forms of oppression and inequality do not function in the same way. But, we found that working thematically, and then providing examples of how those themes play out within different contexts and structures, helps students see patterns and intersections as well as distinctions between particular forms of injustice as they are practiced and institutionalized. For example, we begin with the theme that difference is socially constructed at particular moments in history, becomes embedded in institutions and systems, and creates material inequalities with its hierarchical sorting of humans. We look at this from multiple vantage points, from disability studies to critical race theory to gender studies, privileging personal narratives and historical examples that involve more than one identity category. Likewise, when we work on the theme of the relationship between privilege and oppression, we explore how these dynamics work with Christian privilege, class privilege, white privilege, cisgender, and male privilege. Other themes we explore include everyday intersectionality, modes of resistance, solidarity and accomplicing, and communal vocational discernment. Teaching intersectionally means that students often find themselves simultaneously being challenged and their experiences affirmed in relation to various themes. At times they recognize their own privilege, and at times they recognize how their experiences and embodiment have been targeted and made invisible by social structures and practices of distinction. Our hope is that by working at the intersections, we help build empathy, solidarity, and recognition of difference that will allow our students better to acknowledge, navigate, and dismantle injustice in the everyday interactions of religious leadership. Such work begins in the classroom and, of course, requires committed communal work of all of our lifetimes to complete.

“Doc, if I teach what you are talking about I’ll get fired!” “Talking about this in seminary is fine, but if I try to talk about white supremacy on my job –won’t I get fired?” “If I talk about racism and oppression in my church-I’ll get fired.” In classroom conversations that teach against domination, systemic hatred, violence, and social dehumanization, students begin to consider what it might be like to take these agendas to the places where they have leadership responsibility, authority, and obligation. Students become concerned about what might be at stake should they take up the lofty ideals of equity, liberation, and social holiness. The concern for personal risk is not pervasive, but it is certainly a concern which is voiced. Once students learn a bit about employing liberative pedagogies they become concerned about employment stability, the consequences of moral agency, and the backlash of courageous acts. Students feel inspired, intrigued, and curious about new approaches to the sins of xenophobia, white nationalism, racism, misogyny, Islamophobia, and homophobia, only to be halted by the personal fear of communal rejection, the possibility of shunning, and the chance that they will get fired. After reading great thinkers like bell hooks, Paulo Freire, Katie G. Cannon, Parker Palmer, and Audre Lorde, students lean into the conversation of social transformation and church accountability. They “try-on” the ideas of liberation and the hope of systemic equity for minoritized, economically disenfranchised, and those seeking asylum. There is a thrill to these taboo and previously unconsidered notions of good community and spiritual maturity. Quickly though, too quickly, the thrill meanders into, or slams into, the reality of being a neophyte leader in an established system. Their questions wither into concerns of self-preservation and selfishness–“If I try to do this stuff, will I get fired?” Critical, prophetic wisdom shrivels. Rather than bringing ease, deep study plunges the student into discomfort, dilemma, and the promise of hardship, sacrifice, and possible loss of power, authority, and social stature. In asking if they will get fired, I do not believe my students are having a crisis of conscience–their conscience is clear. They say they want liberation for all persons–and I believe them. Their dilemma is in falling victim to selfishness and the illusion of security. They are afraid that if they lead people toward change, and teach toward an ethic of compassion, love, empathy, and mercy, that this will be such a drastic shift away from the current norm of white supremacy and patriarchy that they will be punished. These genuine concerns must be considered in the seminary classroom if learning about justice is to be real and realized. On the days I am impatient with their self-centered concerns, my answer to their genuine, albeit uninspired, concern is to quote science fiction writer Octavia Butler, “So be it. See to it.” With this statement I am not so much trying to be callous as I am trying to portray what my grandmother told me: “We do not fight flesh and blood, but powers and principalities.” What she meant was that we are obligated to speak our truth then trust in the Spirit who would see us through the fight; our truth and trust must be in God. This is a hard lesson which sometimes takes a lifetime. My grandmother would also import Emily Dickinson’s advice to “tell the truth but tell it slant,” her version of “.. . be wise as serpents and innocent as doves” (Matthew 10:16). When I am more patient, I linger over the question of self-preservation. I carefully explain that the work of teaching to transgress, if done effectively, will likely result at some point in life with the loss of favor, friends, reputation, money, and yes, might result in getting fired. I want my students, even the young ones, to have more fear of the harm and violence of living in a racist society than fear of personal sacrifice. I want them to fear being unfaithful to what they say they care about and believe. I want their fear to motivate them rather than paralyze them. When I ask the student who had the courage to voice their fear of being fired why they would want to lead a congregation or institution who would suppress their impulse to fight against the status quo, I am asking why would they want to squander the gifts they offer for the needs of the world to a people who are uninterested in, or unmoved by, the suffering of the world. Heretofore, my students have heard this as a rhetorical inquiry and no one has responded to this query – not yet. I tell them that failure (like getting fired) is likely one of the better learning opportunities in the teaching journey. Surely, few of us have the wherewithal to prescribe failure or to sabotage our own career, even for justice work. However, when the surprise of failure finds us, we must know this likely signals new opportunity, new fulfillment, the chance for deeper contemplation about the meanness of the world and our role of leadership. Some of my most creative teaching episodes have come from my failures. I must remember to tell my students more stories of when I have failed, what I learned and, most important, point to the fact that I have lived to tell about it. Failure, even when deadly, has not as yet meant my demise. We tell students to live the question – or at least I do. But, they must live the deeper questions and not the shallow ones. If their best reflection question is “Suppose I get fired?” then this narcissistic inquiry will embolden the status quo. Shallow reflexive questions will only serve to undergird mediocrity and leave domination unchecked. Living the big questions of life means, in the 21st century, coming to grips with the fact that there is “no place to escape the diversity of the human community” (P. Palmer). Our pursuit of the deep questions in the public view of teaching will help other people to do things they really want to do, but are too afraid to do by themselves. People want to be good neighbors, want to welcome the stranger, want to live in harmony with dignity, respect and peace. Our job, as learned people, is to provide them with excuses, rationales, and ways to honor these virtues of justice. Those of us who are privileged to have studied cannot retreat into small menial jobs of maintaining the status quo or regress into living quiet lives of desperation hoping to be rescued by the leadership of someone else. Those of us who are educated must take up the big, big, big jobs of life like teaching justice, spreading mercy, and modeling love. We must refuse to be seduced by shallow subsistence which promises a paycheck. Our job of justice is to enunciate so clearly that truth is unmistakable–the truth that there are no inferior people. This enunciation will likely get all of us fired.

Years ago, preparation for the beginning of school was a family affair. The cigar box for storage of pencils, pens, glue, and scissors was gotten by my father from the Pennsylvania State Store. Notebooks, book bags, and new sneakers were on my mother’s to do list. New clothes were my favorite preparation. A plaid skirt and dresses for me. My brother got pants and shirts, enough for the week. For our family, fulfilling this routine meant “we were ready!” for school to start. Now, years later, I am on the other side of the classroom podium. Yes, new shoes have been purchased, but my attention is on a different kind of preparation. I am uneasy and apprehensive. The hatred and moral outrage in the nation is weighing heavily upon my preparation. While racism is woven into the tapestry of USA democracy, we find ourselves in an unrehearsed moment. We are in an era where facts have empirical alternatives, immigrants are disinvited with police action, patriotism is routinely questioned, time-honored value systems are publicly maligned, and core social institutions such as family, religion, parenthood, marriage, and racial identity are under siege. When the classroom doors are flung open the students will likely be thinking about, and undoubtedly affected by, our moral crisis spurred on by recent domestic terrorism and the uninhibited displays of white supremacy. The national conversation about our morally bankrupt and inarticulate president will be on their minds. Or worse yet, if learners have ignored or closed themselves off from the surge of the Klu Klux Klan, the protests in all the major cities, and the many looming international disasters, then when they enter the classroom they will be hoping to continue the delusion of safety and security. Whether immersed in the national conversation or oblivious to it there is a new kind of vulnerability, uncertainty, mistrust and strain in our everydayness – I am unsettled and do not know how to prepare. What does it mean to “get ready” to teach when the national leadership is equivocating and mealy-mouthed about the inferiority and disposability of Blacks, Jews, Latino/s, recent immigrants, Muslims, LGBTQ, and the poor? When students cross the thresholds of our classrooms, their questions, concerns, beliefs, fears, confusions, fatigues, and misgivings will also flood through the door. It would be foolish to hide behind our own scripted syllabi, and then feign surprise when these issues bubble-up. Even if these volatile topics are not discussed forthrightly in our curriculum, students and colleagues alike are likely to act-out their fears and emotional distress. Our classrooms will be altered by the national conversation on hate in America – and rightfully so. My hunch is that the seminal inquiries will come when students (and colleagues) ask about our personal beliefs and values. The instances with the most magnitude are not likely to happen in the drama of a lecture or during a spirited debate in the classroom. I suspect the inquiry will come in subdued moments at the coffee urn or while riding together in an elevator. Students will ask, overtly or in a roundabout fashion, what you personally believe concerning patriotism, moral courage, and race. If you are a teacher with any standing in the faculty, or with any regard in the life of your students, you will be asked about your personal stance on white nationalism and white America. To be asked by your students to guide them with your own moral compass is a powerful request. It is a request that, for some teachers, is beyond our comfort zones and perceived professional boundaries. Tough luck! Students will be listening for the integrity of your conviction, your ability to be genuine about current injustices and the location of your moral passion. Be honest and believable. If we are to seize the power of our authority and step into our responsibility as moral agents who set examples of moral clarity, then we must know what we think before we are asked what we think. The moral volatility of this moment behooves all of us to know what we believe before we are asked - because we will be asked. During your preparation, reflection, and soul searching consider the risk and the cost of your values and weigh them carefully. Meeting the obligation of speaking for justice and against hatred has a price - sometimes a terribly high price. Silence also has its premium. The pundits and politicians cannot be our exemplars. Their disingenuous speak makes their ignorance vivid during the 24/7 news cycle. Most have done little personal or critical reflection – and it shows. When they incorrectly use vocabulary from the politics-of-racism lexicon, speak a-historically as if race politics is new, or reply in shallow, hackneyed clichés we know we are being led by persons who are ill-prepared and outmoded. The failure of moral leadership is, in part, the unwillingness to prepare before speaking. Soundbites cannot rule the day. The wild ride that is Trump’s presidency is only going to become more frenetic and incoherent. The collective experience of dangerous uncertainty and looming demise will not wane but continue to wax into the foreseeable future. The psychological torque produced by this fatigue will weigh heavily upon the stability of our classrooms and upon the teaching know-how we have come to rely upon. Our students, more than ever, will need us to create spaces that help them to make sense of all that is shifting, eroding, and slipping away. As teachers who accept the prophetic nature of our role and responsibility, we must tend to our own body health and keep consistent with our spiritual practices. If you must despair, do it in the privacy of your prayer closet. Allow your students to hear what you believe as a way of integrity and meaning-making. Show them how to create the voice of justice by being a voice for justice. Assure them that democracy can withstand this attack. Then hope like hell that it can.

Cláudio Carvalhaes Associate Professor McCormick Theological Seminary In Brazil There has been a recent uprising of students fighting for justice and better education. Several political developments have spurred the revolt of fourteen- to seventeen-year-old students in defiance of arbitrary laws of governors. Let me mention four events. First, it was

Nancy Lynne Westfield Associate Professor of Religious Education Drew Theological School The proximity of violence is the terror. Violence is not new – it is, for much of our society and in many, many ways, a preferred way of life. The illusion is that violence can be controlled, patrolled, contained,