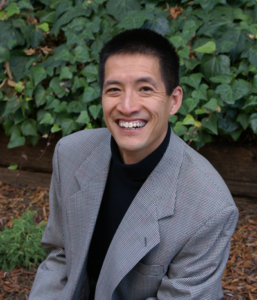

What We Do with Appearance and Assumptions: Our Own and Those of Our Students

It was by now a pretty well-known social experiment. A man dressed like a homeless person collapses on the street and is ignored by pedestrians; when the same person puts on a business suit and collapses on the same street, however, a number of strangers quickly come to his aid.

Unfortunately, appearance does matter, and it matters also in the classroom. Let me turn now to share my own experiences with two students in my very first course that I taught as a full-time professor.

Student One

It was literally my first day of class in the seminary. I was both anxious and excited. After giving out and going through the syllabus, I followed my lesson plan on which I had worked tirelessly all summer long. When time was up, I was secretly congratulating myself for making what I thought to be a wonderful first impression, especially when a couple of students came up to me and said that they were really “psyched” for the course. Then a white woman student who looked to me to be in her fifties introduced herself to me with not only her name but also her credentials. She said that she had a doctorate in adult education and that she could tell that I had little knowledge or experience with adult education (of course, I had told everyone at the beginning of the class that this was my very first year teaching at the seminary). She followed up and commented that my syllabus was too long and too intimidating and that I talked too fast, gave too much material, and failed to provide students any handouts. I was floored and a little embarrassed, but I managed to keep myself calm and said something to the effect that I would try to provide some handouts and that I would always be available for conversations if she had any questions about the course.

Unfortunately, my “invitation” resulted in one after-class encounter that has remained vivid in my memory even almost twenty years later. I had just returned a written assignment to the class, and this woman came up after class again and asked me why she got a particular grade. (It was not a bad grade, as I remember that it was in the B range.) Since I always provide ample comments on student papers, I pointed those out and explained that her paper could be better and more tightly organized. To my surprise, she responded by saying that my “problem” had to do with the fact that English was not my first language and that I did not understand that there was a kind of writing “in the West” known as stream-of-consciousness.

Unfortunately, my “invitation” resulted in one after-class encounter that has remained vivid in my memory even almost twenty years later. I had just returned a written assignment to the class, and this woman came up after class again and asked me why she got a particular grade. (It was not a bad grade, as I remember that it was in the B range.) Since I always provide ample comments on student papers, I pointed those out and explained that her paper could be better and more tightly organized. To my surprise, she responded by saying that my “problem” had to do with the fact that English was not my first language and that I did not understand that there was a kind of writing “in the West” known as stream-of-consciousness.

Would she feel the same liberty to approach a white male professor and say something like this if she got a B-range grade from him? I think not.

Student Two

It was time to look at my very first set of course evaluations as a full-time professor. This time, I was more anxious than excited. One particular student comment stood out among the—thankfully—many affirmative and encouraging evaluations that I had received.

This student basically said he or she had gotten to the classroom feeling very tired from a long day of work as well as feeling rather frustrated as this was his or her first day in seminary. Sitting at the back of the classroom, this student said he or she felt even worse when I walked into the classroom and stood behind the lectern as the instructor for the course. I could not repeat it verbatim but it went something like this: “I could tell it was going to be a disaster as soon as I saw him, but then Professor Liew started to speak and I was immediately energized and engaged.”

I am grateful and glad that, based upon a very positive evaluation, this particular student was able to learn from me and with me, but what this student assumed upon just seeing me is most telling. Why would he or she make the foregone conclusion that the course was going to be bad as soon as I showed up?

Yes, there is another “appearance” that one cannot change as easily as putting on or taking off a piece of garment. These two students taught me early on in my teaching career that students carry all kinds of assumptions, racialized or otherwise, with them into the classroom, and so I have to be prepared for them. Of course, we as teachers are not immune to this: we have assumptions that lead us to think, act, speak, and make evaluations in particular ways with particular persons. If teaching is truly one of the best ways to learn, I want and need to learn from these early experiences in my teaching career how students may also need to prepare for class in ways that go way beyond what are listed on their syllabi.

Allow me to share the following video by some students at the Rhode Island School of Design as we all work to plan and prepare for the beginning of a new academic year (note that the video contains strong language that some may find offensive). The video raises a host of issues and questions to consider. What questions arose for you as you think about your own teaching? What might it mean for students and teachers to “veil” themselves in classroom contexts?

Social DNA comes with the bodies that enter our classrooms, but it can also be addressed and even changed by what we do in our classes.

Leave a Reply