Teaching the Not Visible

My grandmother used to speak in adages, parables, metaphors, similes and symbols. Now I call her proclivity for language, literature, and meaning-making “wisdom-speak.” Then, I thought she was being corny. She knew her wisdom-speak was meant to teach me enough until I am ready to know more.

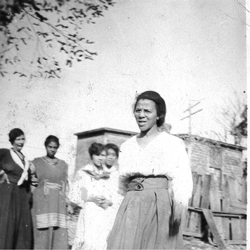

Her adages came from bible verses, poetry lines, and quotes from novels, cultural remembrances and living life as an African American woman in the USA, born in 1887. Folks like Langston Hughes, Booker T. Washington, Sojourner Truth, Pearl Bailey, Jesus, and Sarah Vaughn were regularly invoked.

Wisdom-speak is colorful, witty language - easy to recall and recite, with a depth of multiple meanings. Wisdom-speak is part of everyday conversation. It is a pithy quote or well-placed refrain woven into a conversation like salt on fried fish. It is accompanied by a hmmm or tongue click, a foot pat, a shoulder shrug or an eye roll. Wisdom-speak is a body, mind and spirit lesson.

Grandmother Vyola would say, “All that is is not visible.” As a child, I thought she meant that there is more to creation than what can be witnessed with the naked eye. If knowing is only about what is directly in front of us – then we miss so very much of all that is. Learning to see the invisible is the task of knowing. Learning the ways of the wind and the saints, angels, ancestors, cherubim and seraphim; the dream world and the day dreaming world; the ways of prayer and meditation are the learning of the invisible.

Grandmother Vyola would say, “All that is is not visible.” As a child, I thought she meant that there is more to creation than what can be witnessed with the naked eye. If knowing is only about what is directly in front of us – then we miss so very much of all that is. Learning to see the invisible is the task of knowing. Learning the ways of the wind and the saints, angels, ancestors, cherubim and seraphim; the dream world and the day dreaming world; the ways of prayer and meditation are the learning of the invisible.

Then as a young adult, I decided she was talking about identity politics and the politics of domination. The genderless politics of patriarchy, with its racist undertones and dictates, considers much of “all that is” to be too much for women, many children, and most men. The truncation of imagination engineered by systems of domination and control renders the capacity of many people as inferior thus negating all that is. Poverty drastically limits opportunities for in-depth exploration – so when we meet persons who have carved out an education in the wake of social depravity we should be in awe. As a young adult, I came to understand good teaching meant finding ways of seeing the manifestations of oppression in my own classrooms, church, society, and world.

And I encountered Alice Walker and figured Grandmother Vyloa was talking about what Dr. Walker was talking about. Grandmother Vyola is resonant with novelist, poet Alice Walker’s  four-part definition of a “Womanist” from In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose, 1983. The first part of the definition reads in part: “….Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered ‘good’ for one.” It seems as though Vyola and Alice were cut from the same cloth.

four-part definition of a “Womanist” from In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose, 1983. The first part of the definition reads in part: “….Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered ‘good’ for one.” It seems as though Vyola and Alice were cut from the same cloth.

In the last few days, I have turned my attention exclusively toward preparation for school. I have my head down as I put finishing touches on my syllabi, design learning activities, schedule guest colleagues, locate films, and order art supplies. My mode is one of efficiency and my mood is closed off. I am, in my planning, working from an attitude of indubitability. I have a clarity about what I will teach, how I will teach and what my students will learn.

While immersed in my preparations, grandmother whispered in my ear. Grandmother Vyola says that patent planning is not good for me or my students. She advises that the better way is to be more opened ended – like Jesus’ parables. Allow the students’ voice to affect most aspects of the course design, not just the convenient parts. Consider that you cannot see all there is to see so leave room for your own learning while you teach. Most of all, the plan that that which is revealed will be marvelous and know it is unplannable, but can be readied for – Get Ready!

I have learned to pause when grandmother speaks. I take a second look at my plans and see that I have relied, a bit, on stale redundancy and a few too many current conventions. I recognize that when I start telling myself I know what will happen, what can happen in my own classroom – I am in danger of not allowing for surprise, the unexpected, or the un-expectable activity of Spirit. My grandmothers Vyola and Alice remind me that my certainty is likely a trap. If I plan for only what I know, only what I can see, only for what I can do – then I am not being womanish, not acknowledging all that is in the world.

With this wisdom, I have begun to incorporate more ways of acknowledging the hegemonic forces which hide in our midst. I have adjusted and added ways which invoke the freedoms of learning for my students – freedoms like their own questioning, curiosity, and concerns being integrated into the full length of the course.

School starts the week before Labor Day --- I am less certain of my plans and better for it.

Leave a Reply