As the National Guard is deployed in Los Angeles, tear gas flows, rubber bullets punish bystanders, and cars burn, I cannot help but think about how undocumented immigration and mass deportations have become racially charged. I hear some people ask, “Who are these people?” Part of the issue is that the words used to describe Latin@s, such as “Hispanic” or even “Latino,” are not racial markers. They are used to describe a vast conglomeration of people who are diverse in and of themselves. The term is as broad as “American” or “European.”

For example, I am Honduran-American. My ethnic heritage is Honduran, but even then, two of my four grandparents were from El Salvador. These are two countries that went to war in the “Football [Soccer] War” of 1969. Honduras has enjoyed relative peace, but El Salvador was embroiled in a prolonged Civil War from 1980 until 1992. Even now, there are sharp differences: El Salvador has elected Nayib Bukele, an authoritarian right-wing politician, while Honduras elected Xiomara Castro, a left-wing socialist. I know I may be teasing out fine details, but these countries are different. Yet they are all lumped together under one category that erases nuance: Hispanic.

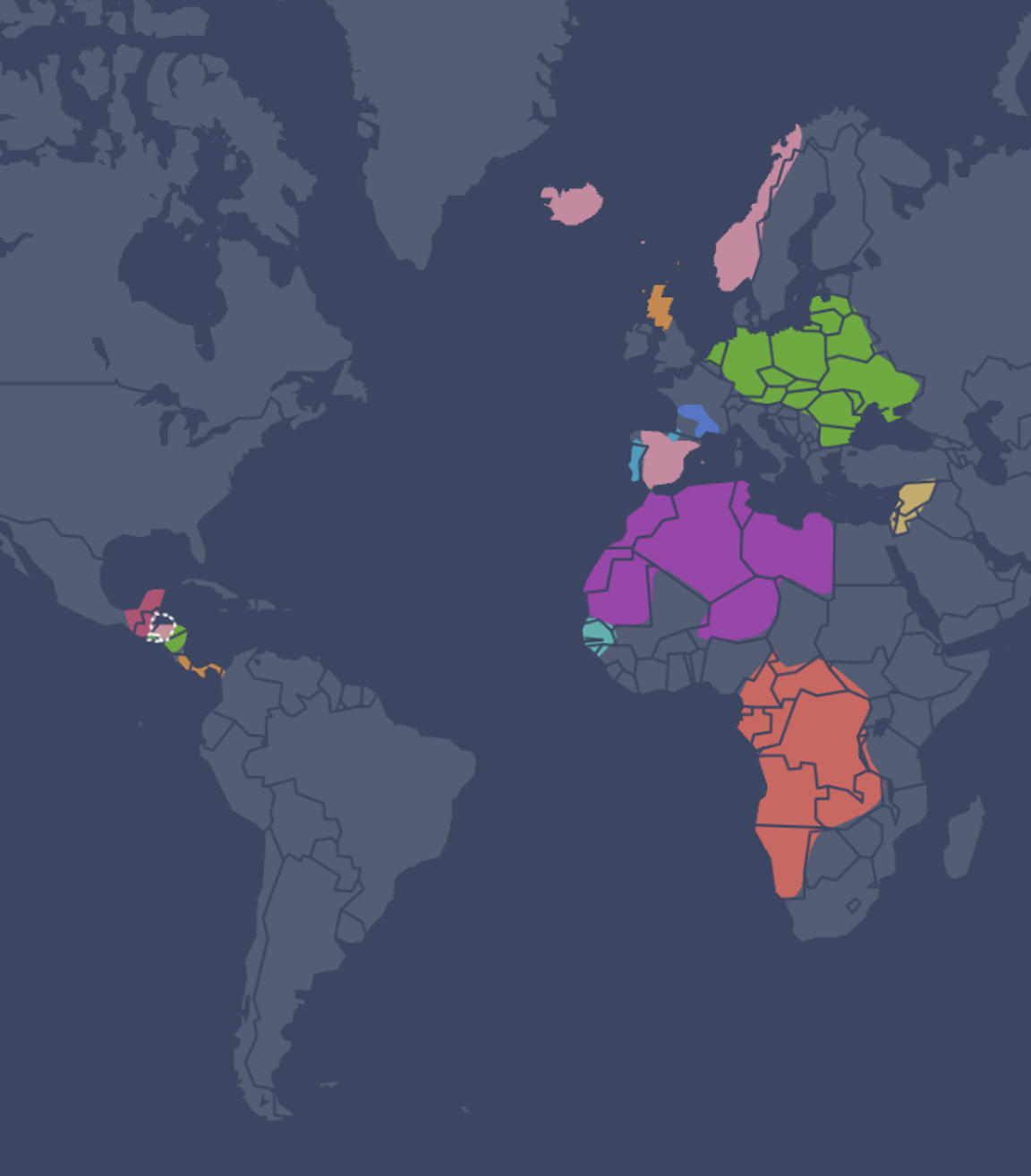

The differences extend further. Honduras and Mexico are distinct in many ways, and Honduras and Argentina even more so. Within Honduras itself, regions differ significantly, and the country is also home to non-Hispanic peoples such as the Garinagu, descendants of escaped African slaves and Carib peoples from Saint Vincent. El Salvador is similar but not the same. Traveling across Central and South America, I have often felt as though I had arrived at “the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

Hispanic is a term that primarily refers to someone who speaks Spanish. In Europe, it specifically refers to people from Spain. In Spain, there is the concept of hispanoamérica, which points back to the colonial period. Certainly, we share much common history. Spain influenced our languages, religions, and customs. Yet there are places where this dominance barely penetrated. Even in religion, syncretism with African and Amerindian traditions remains strong. Moreover, many other languages are spoken in Latin America. The term Hispanic does not capture this diversity, nor does it account for the racial intermixing—or mestizaje—that has defined Latin America.

This racial intermixing is key to understanding Latin America. Through it, Latin Americans have built their societies and cultures. For example, the DNA test I took displays my own racial ambiguity. Being Hispanic is not a race. As my results show, my genetic makeup is one of miscegenation. In terms of traditional U.S. laws, I am an aberration. Consider Loving v. Virginia, when Richard and Mildred Loving could not legally marry across racial lines. For much of U.S. history, interracial marriage was prohibited. By those outdated laws, many Latin Americans—racially ambiguous by nature—would already have been considered “illegal.”

I cannot underscore the importance of this enough. I am simultaneously African, Amerindian, European, Jewish, and Palestinian. When people ask what race I am, I tell them there is only one race—the human race. The differences between human beings are minimal. Some have more pigmentation than others, but we all share similar needs.

Culture and ethnicity, which are learned and ingrained, account for much of what differentiates us. This is where living together becomes difficult. For example, in Latin America there are constant jokes about cultural differences. Puerto Rican culture is direct and upfront, and people will tell you plainly what they think. To other cultures, this can seem aggressive. By contrast, Guatemalan culture often avoids eye contact. To outsiders, this can be misread as dishonesty or passivity.

Even the way we speak Spanish can offend across cultures. In Honduras, we use a form of Spanish called voseo. Our word for “you” is vos. In Spain, Mexico, and Puerto Rico, however, people use tuteo, where “you” is tú. To someone unfamiliar with vos, it can sound aggressive or belittling. But vos is in fact an ancient and reverential form of Spanish, once used to address people of high status. In Honduras, it has become the informal and intimate way to address someone, carrying a sense of closeness that tú or usted do not.

This is the reality of Latin America. Perhaps Latin@s anticipate a future in the United States where miscegenationbecomes the norm. In many ways, this holds promise. We can become a family. We can live and work together to forge a shared future. We are stronger united than divided. Our obsession with Black and White categories could be made more nuanced. At the same time, tensions persist. Yet there is beauty in our African and Amerindian roots. The potential for racial harmony is present. But we must recognize it, claim it, and live into that promise. As one song says, “there is no future in [racial] purity.”

Notes & Bibliography

Jarabe de Palo. “En lo puro no hay futuro.” YouTube, uploaded by Jarabe de Palo, 23 Sept. 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=1GoNN7Mxu_U. Accessed 20 June 2025.